Robert Higgs • Thursday, January 19, 2017 •

Many Americans (and others) obviously fear corporations more than they fear governments. Indeed, they look to governments to “save” them from grave harm at the hands of vicious corporations and to punish corporations for their evil, destructive actions. On such a mindset a large part of modern Progressivism and other leftist ideologies rests.

Many Americans (and others) obviously fear corporations more than they fear governments. Indeed, they look to governments to “save” them from grave harm at the hands of vicious corporations and to punish corporations for their evil, destructive actions. On such a mindset a large part of modern Progressivism and other leftist ideologies rests.

R. J. Rummel’s compilations show that approximately 262 million persons were deliberately killed by “their own” governments during the twentieth century alone—many times the number of death’s in that century’s international wars. Rummel calls this death toll “democide.”

It would be an interesting exercise for someone to compile the data for “corporacide,” the number of people deliberately killed by corporations in the same period, the time during which such business organizations were, so to speak, riding highest.

Aside from the fact that corporacide would be found, I am confident, to be close to zero—after all, as a rule, killing people is bad for business—one might call attention to the fact that corporations and other, similar business firms have been responsible for generating the bulk of the wealth that has lifted most of the world’s people out of poverty during the past century or so and for making a substantial portion of the world’s population affluent.

The combination “hate corporations/love governments” has to be one of the most bizarre ideological monstrosities of the past 150 years. It seems that people in general are utterly incapable of recognizing real threats and distinguishing them from threats that are inconsequential by comparison or actually not threats at all. Ideology’s power to blind people and twist their understanding is truly astonishing.

John R. Graham • Thursday, January 19, 2017 •

As Congress and President-elect Trump debate how to repeal and replace Obamacare, the obsession with health insurance, rather than actual access to health care, has dominated the debate. It invites the question: How have jobs in health insurance fared before and after Obamacare?

As Congress and President-elect Trump debate how to repeal and replace Obamacare, the obsession with health insurance, rather than actual access to health care, has dominated the debate. It invites the question: How have jobs in health insurance fared before and after Obamacare?

They have boomed! Before the Great Recession, nonfarm civilian employment peaked in January 2008, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It bottomed out in February 2010, with 6.28 percent of jobs having disappeared over 25 months. (The Affordable Care Act was signed in March 2010.) Nonfarm civilian employment recovered its losses in May 2014, and has grown since then. As of last November, nonfarm civilian payrolls had increased 11.88 percent from the February 2010 low, and 4.85 percent from the January 2008 peak.

Robert Higgs • Wednesday, January 18, 2017 •

The interrelated complex of ideology, identity, solidarity, and collective action form the ground level in fruitful social analysis. Leaving out this complex, as both mainstream and Austrian economists usually do, means that one sacrifices the opportunity to understand what otherwise seems inexplicable or gets explained only by bizarrely twisting the standard model.

The interrelated complex of ideology, identity, solidarity, and collective action form the ground level in fruitful social analysis. Leaving out this complex, as both mainstream and Austrian economists usually do, means that one sacrifices the opportunity to understand what otherwise seems inexplicable or gets explained only by bizarrely twisting the standard model.

At least, so I have argued since the early 1980s, most fully in chapter 3 of Crisis and Leviathan, but with some elaboration and many applications in later works. I sometimes forget this lesson myself, lapsing into a too vulgar reliance on “following the money,” but Elizabeth always calls me back to it. For just such correction, I suppose, God gives wives to husbands.

The events of U.S. politics during the past year present as glaring an example of my vision as anything I know. It’s comfortable for many of us, especially those trained in mainstream economics, to suppose that economic self-interest is the bedrock of political and other collective action, but clearly—in my view, at least—it is not. Ideology tells a person what is “in his interest”; he shapes and maintains his identity accordingly; and by acting publicly in conformity with the ideology’s tenets, the person enjoys the psychological satisfaction of solidarity among the ideologically defined “good guys.” As Sam Bowles once noted, people act for two distinct reasons: to get things, and to be someone. We would do well to remember the second motive, which plays a central role especially in relation to people’s participation in large-group collective action.

Abigail R. Hall • Wednesday, January 18, 2017 •

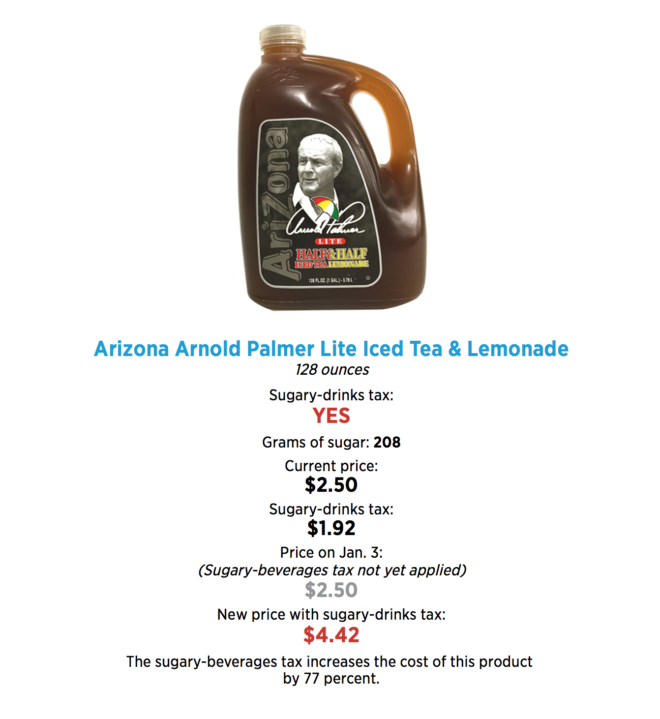

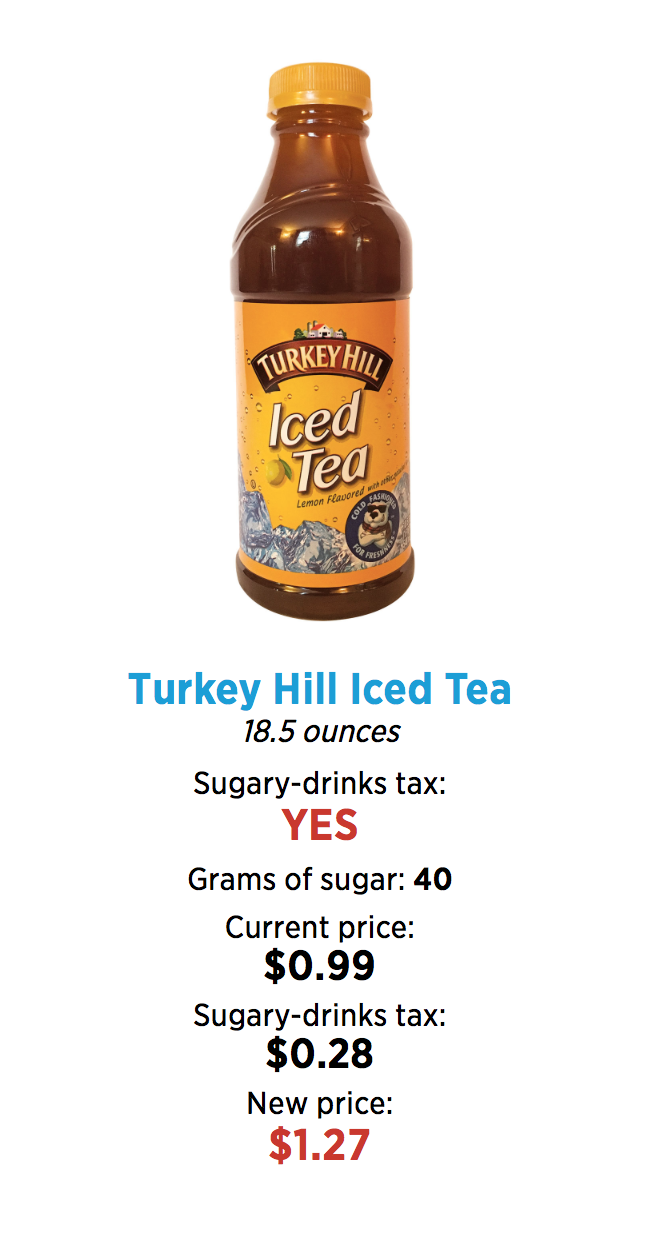

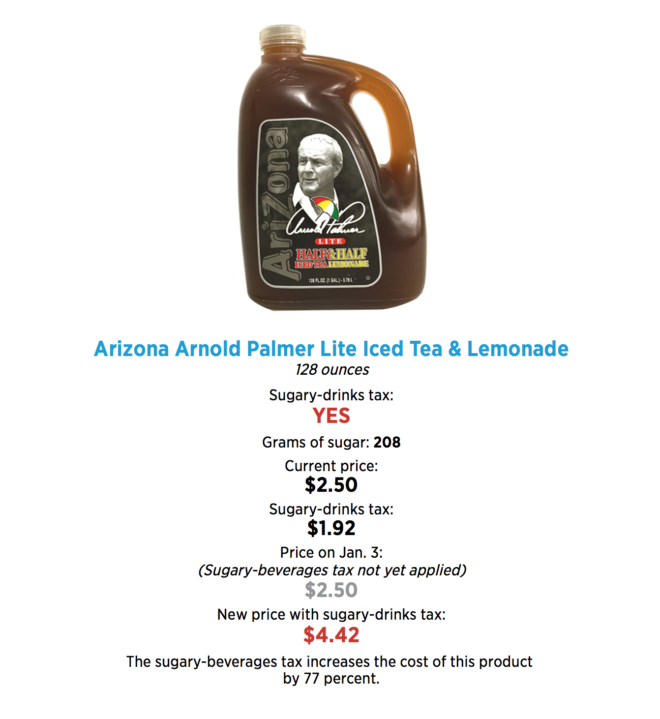

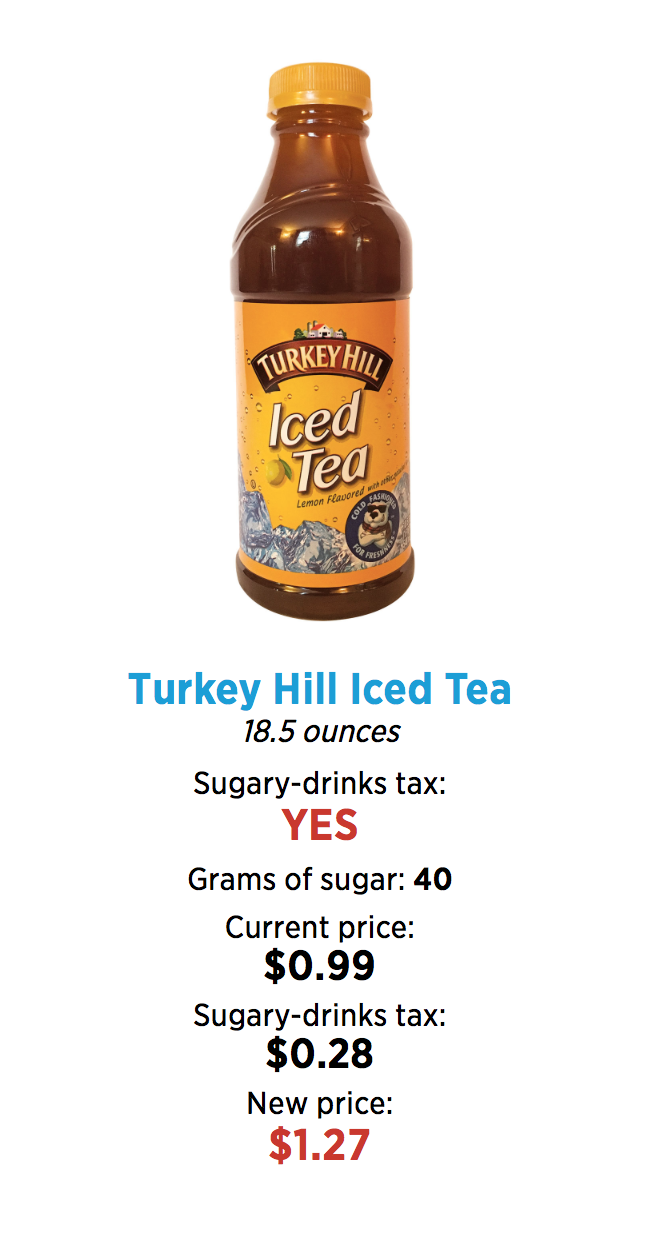

On January 1, the city of Philadelphia enacted a soda tax, or a “Sweetened Beverage Tax ” (SBT). The new policy levies a tax of 1.5 cents per ounce on most drinks containing a sugar-based sweetener or artificial sugar substitute (e.g. high fructose corn syrup).

The following infographics from the Philadelphia Inquirer show the impact of the tax on the price of many beverages.

Proponents of the tax like Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney, argue that the tax will bring in millions of dollars that may be used for a variety of programs. He’s suggested that the money collected will be used to expand pre-K education, rebuild parks across the city, and open community schools. He also proposed investing millions into the city’s pension system (currently facing a multi-billion dollar deficit) and to pay back a bond on “green” infrastructure improvements.

It’s easy to see how people like Mr. Kenney believe this tax will be a cash cow for the city. With a tax of $2.40 on an 8 pack of Gatorade, a $0.30 tax on a 20 ounce bottle of Coca-Cola, a $1.01 tax on a 2-liter of Pepsi, and a whopping $2.50 tax on a gallon of sweet tea, there’s the potential for millions in revenue.

Alas, that pesky thing called economics may throw a wrench in Kenney’s grand plans.

John R. Graham • Tuesday, January 17, 2017 •

Obamacare’s least popular feature is the individual “mandate” to have health insurance. This requirement was the subject of the 2012 lawsuit asserting Obamacare was unconstitutional: Never before had the federal government forced any resident to buy a good or service from a private business.

Obamacare’s least popular feature is the individual “mandate” to have health insurance. This requirement was the subject of the 2012 lawsuit asserting Obamacare was unconstitutional: Never before had the federal government forced any resident to buy a good or service from a private business.

The people lost that argument. Nevertheless, whether we label the punishment for disobeying the mandate a fine or a tax, it is a very inefficient way to raise money to finance health care.

The IRS also follows the money going in the other direction: Tax credits paid out to insurers which offer policies in Obamacare’s exchanges. Although paid to insurers, the tax credits are applied to individuals’ premiums. One of the problems is that taxpayers have to guess how much money they will earn in a year, because the tax credits phase out in a confusing way. A beneficiary might be surprised to learn that he has to refund tax credits to the IRS!

Randall G. Holcombe • Tuesday, January 17, 2017 •

As the inauguration of Donald Trump approaches, this article says “A growing number of Democratic lawmakers are boycotting President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration,” and “Some members of Congress have said they will be protesting in Washington, D.C., and in their districts instead.” What are they protesting?

As the inauguration of Donald Trump approaches, this article says “A growing number of Democratic lawmakers are boycotting President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration,” and “Some members of Congress have said they will be protesting in Washington, D.C., and in their districts instead.” What are they protesting?

The article gives brief statements from 25 Democrats who say they won’t attend, and many say their decisions are based on their being offended by statements Trump has made both before and after the election.

One of the 25 questions the legitimacy of the election, and several mention the likelihood that Trump will promote policies they don’t like. Examples include appointing a Supreme Court Justice, environmental policies, health care reform, and policies that hurt women and immigrants. But Trump hasn’t nominated any Supreme Court Justices, or as president-elect, moved forward on any of these polices, or even been specific about policies he might pursue. These members of Congress are protesting what they think Trump might do, not what he has done.

William J. Watkins, Jr. • Tuesday, January 17, 2017 •

In January, the winds of political change often blow with ferocity. The District of Columbia is now bracing itself for a gale-force disruption as Donald Trump prepares to become the 45th President of the United States. An upheaval in foreign affairs, trade, and immigration policy is in the offing.

In January, the winds of political change often blow with ferocity. The District of Columbia is now bracing itself for a gale-force disruption as Donald Trump prepares to become the 45th President of the United States. An upheaval in foreign affairs, trade, and immigration policy is in the offing.

It’s tempting to focus solely on the changes Mr. Trump has promised, but the public and the incoming administration should reserve some time to remember their history—and learn from it. January 14 marked the 233rd anniversary of the Confederation Congress’s ratification of the Treaty of Paris, the agreement that formally ended the Revolutionary War between Great Britain and the United States.

Not long after British General Charles Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown to General Washington, peace talks began in the French capital. Great Britain was represented by Richard Oswald, and the United States by Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and John Adams.

Robert Higgs • Tuesday, January 17, 2017 •

Fake news has been a hot topic recently. All sides of the political sound and fury surrounding the recent presidential election have leveled charges and counter-charges against their opponents in this regard. Democrats, embracing a newfound, touchingly naive faith in the CIA and the other agencies of the so-called intelligence community, have claimed that the Russians hacked the Democratic strategists’ electronic files, released the information gained thereby, and hence influenced the election in Trump’s favor, costing Clinton the victory she so amply deserved. Republicans have responded that such claims at best evince sour grapes and an attempt to shift the public’s attention from the substance of the revealed messages to the identity of the messengers who allegedly made them public. At the same time, libertarians and others have called attention to the fact that the government itself is and long has been a leading, if not the leading, propagator of fake news—sometimes called simply propaganda—in its various attempts to sway public opinion and diminish resistance to its schemes for aggrandizing its own power and enriching the crony capitalists on whom it relies for its principal financial support, especially during the electioneering season.

Fake news has been a hot topic recently. All sides of the political sound and fury surrounding the recent presidential election have leveled charges and counter-charges against their opponents in this regard. Democrats, embracing a newfound, touchingly naive faith in the CIA and the other agencies of the so-called intelligence community, have claimed that the Russians hacked the Democratic strategists’ electronic files, released the information gained thereby, and hence influenced the election in Trump’s favor, costing Clinton the victory she so amply deserved. Republicans have responded that such claims at best evince sour grapes and an attempt to shift the public’s attention from the substance of the revealed messages to the identity of the messengers who allegedly made them public. At the same time, libertarians and others have called attention to the fact that the government itself is and long has been a leading, if not the leading, propagator of fake news—sometimes called simply propaganda—in its various attempts to sway public opinion and diminish resistance to its schemes for aggrandizing its own power and enriching the crony capitalists on whom it relies for its principal financial support, especially during the electioneering season.

Fake news is as old as news itself. Political reporting in particular has always served as a tool of those who hold or seek to gain a grip on power. Respectable news sources, such as the New York Times and the Washington Post, are not and never have been strangers to the distribution of false, twisted, or selectively partial and slanted reports. Less prestigious news outlets have also played the game. Perhaps the only new development on this front recently is the use of the Internet to spread fake news quicker and farther than the old media could. The news cycle revolves constantly now, and hence news, true and false, is placed before the public on an instant, worldwide scale as never before.

John R. Graham • Thursday, January 12, 2017 •

President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) has issued its valedictory report on the state of Obamacare. The gist of its argument is that Obamacare is doing fine, on the verge of overcoming its growing pains since 2014.

President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) has issued its valedictory report on the state of Obamacare. The gist of its argument is that Obamacare is doing fine, on the verge of overcoming its growing pains since 2014.

Critics (like me) who suspect the 25 percent increase in premiums for 2017 are a problem are off-base, according to the CEA. In a normal insurance market, such an increase would indicate a “death spiral”: The sick enroll and the healthy stay away, causing next year’s premiums to increase. The cycle repeats itself until only the sickest enroll. The CEA asserts this cannot be occurring because 11.3 million people enrolled in Obamacare last December, which was 300,000 more than in December 2015. Further, insurers underpriced their policies in 2014 because the market was new. However, they have learned since then and are pricing policies more realistically.

While it is true that enrollment in Obamacare’s market is a little higher than last year, it is still well below the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of 21 million enrollees in 2016, which it made as recently as March 2015. Even in January 2016, it estimated 13 million would enroll last year, which was almost one-fifth too high.

The major factor preventing enrollment from collapsing is that Obamacare’s tax credits ratchet up to blunt the pain of enrollees’ premium hikes. If the tax credit were a fixed-dollar premium, many enrollees would bail out rather than suffer a 25 percent gross premium increase. Further, the amount of people defined as “sick” has increased since Obamacare launched. Recall that U.S. life expectancy declined among both men and women of all ethnic groups in 2015, for the first time since 1993.

Abigail R. Hall • Wednesday, January 11, 2017 •

It seems like Venezuela always provides great classroom examples for all the wrong reasons.

It seems like Venezuela always provides great classroom examples for all the wrong reasons.

I’ve written on this blog multiple times about the government of Venezuela and the polices it has enacted. I’ve argued that falling oil prices aren’t to blame for the country’s troubles and that the once-high oil prices only masked the underlying shortages caused by government policy. I’ve discussed how the major price controls put in place in Venezuela have made it difficult to impossible for people to find goods ranging from toilet paper and feminine hygiene products, to meat and flour.

Here we are again. The Venezuelan government is once again proving its complete ignorance of basic economics. Its people are paying the price. According to the BBC, Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro announced that the country’s minimum wage and pensions would increase by 50 percent in an effort to combat the country’s rampant inflation, which the IMF projects will reach 1,600 percent this year. The monthly wage will now be over 40,000 bolivars—about $60 at the official exchange rate ($12 on the black market). For perspective, this is about enough money to purchase a single pair of pants.

In discussing the minimum wage increase (the fifth in the past year), Maduro stated, “To start the year, I have decided to raise salaries and pensions. In times of economic war and mafia attacks…we must protect employment and workers’ income.”

Yikes. Where do we start?

Many Americans (and others) obviously fear corporations more than they fear governments. Indeed, they look to governments to “save” them from grave harm at the hands of vicious corporations and to punish corporations for their evil, destructive actions. On such a mindset a large part of modern Progressivism and other leftist ideologies rests.

Many Americans (and others) obviously fear corporations more than they fear governments. Indeed, they look to governments to “save” them from grave harm at the hands of vicious corporations and to punish corporations for their evil, destructive actions. On such a mindset a large part of modern Progressivism and other leftist ideologies rests. As Congress and President-elect Trump debate how to repeal and replace Obamacare, the obsession with health insurance, rather than actual access to health care, has dominated the debate. It invites the question: How have jobs in health insurance fared before and after Obamacare?

As Congress and President-elect Trump debate how to repeal and replace Obamacare, the obsession with health insurance, rather than actual access to health care, has dominated the debate. It invites the question: How have jobs in health insurance fared before and after Obamacare? The interrelated complex of ideology, identity, solidarity, and collective action form the ground level in fruitful social analysis. Leaving out this complex, as both mainstream and Austrian economists usually do, means that one sacrifices the opportunity to understand what otherwise seems inexplicable or gets explained only by bizarrely twisting the standard model.

The interrelated complex of ideology, identity, solidarity, and collective action form the ground level in fruitful social analysis. Leaving out this complex, as both mainstream and Austrian economists usually do, means that one sacrifices the opportunity to understand what otherwise seems inexplicable or gets explained only by bizarrely twisting the standard model.

Obamacare’s least popular feature is the individual “mandate” to have health insurance. This requirement was the subject of the 2012 lawsuit asserting Obamacare was unconstitutional: Never before had the federal government forced any resident to buy a good or service from a private business.

Obamacare’s least popular feature is the individual “mandate” to have health insurance. This requirement was the subject of the 2012 lawsuit asserting Obamacare was unconstitutional: Never before had the federal government forced any resident to buy a good or service from a private business. As the inauguration of Donald Trump approaches,

As the inauguration of Donald Trump approaches,  In January, the winds of political change often blow with ferocity. The District of Columbia is now bracing itself for a gale-force disruption as Donald Trump prepares to become the 45th President of the United States. An upheaval in foreign affairs, trade, and immigration policy is in the offing.

In January, the winds of political change often blow with ferocity. The District of Columbia is now bracing itself for a gale-force disruption as Donald Trump prepares to become the 45th President of the United States. An upheaval in foreign affairs, trade, and immigration policy is in the offing. Fake news has been a hot topic recently. All sides of the political sound and fury surrounding the recent presidential election have leveled charges and counter-charges against their opponents in this regard. Democrats, embracing a newfound, touchingly naive faith in the CIA and the other agencies of the so-called intelligence community, have claimed that the Russians hacked the Democratic strategists’ electronic files, released the information gained thereby, and hence influenced the election in Trump’s favor, costing Clinton the victory she so amply deserved. Republicans have responded that such claims at best evince sour grapes and an attempt to shift the public’s attention from the substance of the revealed messages to the identity of the messengers who allegedly made them public. At the same time, libertarians and others have called attention to the fact that the government itself is and long has been a leading, if not the leading, propagator of fake news—sometimes called simply propaganda—in its various attempts to sway public opinion and diminish resistance to its schemes for aggrandizing its own power and enriching the crony capitalists on whom it relies for its principal financial support, especially during the electioneering season.

Fake news has been a hot topic recently. All sides of the political sound and fury surrounding the recent presidential election have leveled charges and counter-charges against their opponents in this regard. Democrats, embracing a newfound, touchingly naive faith in the CIA and the other agencies of the so-called intelligence community, have claimed that the Russians hacked the Democratic strategists’ electronic files, released the information gained thereby, and hence influenced the election in Trump’s favor, costing Clinton the victory she so amply deserved. Republicans have responded that such claims at best evince sour grapes and an attempt to shift the public’s attention from the substance of the revealed messages to the identity of the messengers who allegedly made them public. At the same time, libertarians and others have called attention to the fact that the government itself is and long has been a leading, if not the leading, propagator of fake news—sometimes called simply propaganda—in its various attempts to sway public opinion and diminish resistance to its schemes for aggrandizing its own power and enriching the crony capitalists on whom it relies for its principal financial support, especially during the electioneering season. President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) has issued its

President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) has issued its  It seems like Venezuela always provides great classroom examples for all the wrong reasons.

It seems like Venezuela always provides great classroom examples for all the wrong reasons.