One of the zanier features of American politics is the Senate’s filibuster rule. Long ago, the Senate, by a simple majority vote, ruled that a supermajority is required to get any business done, with the result that often nothing gets done at all.

One of the zanier features of American politics is the Senate’s filibuster rule. Long ago, the Senate, by a simple majority vote, ruled that a supermajority is required to get any business done, with the result that often nothing gets done at all.

On the positive side, however, the threat of a filibuster has given the Senate a reputation for being more deliberate in its actions than the House of Representatives. It has often saved the country from legislation being ramrodded through the way it frequently is in the House.

In 2013, the Democrat-controlled Senate voted, 52 to 48, to waive the supermajority rule for the confirmation of federal judges, though not for the Supreme Court. At that time, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell threatened, “I say to my friends on the other side of the aisle, you’ll regret this. And you may regret it a lot sooner than you think.” (New York Times, 11/22/13)

Now that the Republicans are back in power, it is therefore just a matter of time until they reciprocate and eliminate the filibuster altogether, beginning perhaps with the confirmation of Judge Neil Gorsuch. This so-called “Nuclear Option” will push the Republican agenda through, but regrettably it will also abase the Senate to the same low level as the House.

However, there is a third option between the filibuster and immediately passing unread bills with a simple majority, that allows the Senate to mull over contentious bills and appointments without blocking its business entirely. Under this “Mullibuster” option, any bill or confirmation that failed to pass by a 3/5 margin would be subject to tabling for a period of say 2 weeks, at which time it would come back for a new vote. If at that time the bill was exactly the same, it would require only a simple majority to pass. But if it has been amended in the meantime, the revision would be subject to the same Mullibuster rule.

The two week delay would give Senators, their staffs, and the blogospheric public time to actually read the bill, to scrutinize it for flaws, and to rally support or opposition back home. Perhaps the Senate would make the Mullibuster automatic for all measures that failed to gain 3/5 support, or perhaps it would require the formal request of one or more of the dissenting Senators.

If the Senate does adopt the Mullibuster, the House might even be shamed into adopting a similar rule…

See also my Feb. 1 post, “Term Limits for Supreme Court Justices?”

Update 3/28/17:

In a March 20 post entitled The Filibuster: A Primer on the Cato Institute’s blog Cato at Liberty, Robert A. Levy argues that the filibuster rule should be retained, and even written into the Constitution, “especially for votes on significant expenditures and tax increases — and also for confirmation of federal judges, who have lifetime tenure on the bench. Unless and until we establish judicial term limits, it’s little enough to insist that lifetime appointees be approved by 60 senators.”

Levy, an attorney who is Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Cato Institute, clarifies that while it would be straightforward to change Senate rules by a simple majority at the beginning of a session, current Senate rules allow mid-session rule changes themselves to be filibustered, with a 2/3 threshold for cloture. The true “nuclear option,” invoked by Democrats in 2013, “is a point-of-order, upheld by the presiding officer, declaring that the 67-vote requirement is unconstitutional.”

In an earlier post on this blog, I’ve concurred with Levy that there should be term limits on judicial appointments, but I think this is a separate issue from the filibuster.

In another earlier post on this blog, I’ve argued for an “Improved Balanced Budget Amendment” that would restrain deficits by requiring a supermajority vote in both houses to raise a constitutional limit on the national debt, with an “Anti-Chicken Mechanism” that would require the President to impound whatever expenditures are necessary to stay within that limit. However, I would not require a supermajority vote on individual appropriation bills.

Levy suggests no middle ground between retaining the filibuster as is and abolishing it altogether. He concedes that the latter now appears to be inevitable.

Gordon Tullock used to taunt anarchists by asserting that if the USA abolished its government, people would not have to worry about the Russians taking over the country because “the Mexicans would get here first.”

Gordon Tullock used to taunt anarchists by asserting that if the USA abolished its government, people would not have to worry about the Russians taking over the country because “the Mexicans would get here first.” Local governments produce lots of services that people value: schools, police protection, water and sewer services, and more. Who are the producers of these services accountable to, and who determines the characteristics of the services local governments provide?

Local governments produce lots of services that people value: schools, police protection, water and sewer services, and more. Who are the producers of these services accountable to, and who determines the characteristics of the services local governments provide? The tendency of the USA to have a negative balance of trade (more accurately known as a negative balance on current account) played a prominent role in the recent U.S. presidential campaign. Donald Trump criticized this tendency repeatedly and promised that if elected he would take various actions to reduce or eliminate it. Like most members of the public, Trump views this negative balance as a highly undesirable, economically damaging condition. Despite the prominence of discussions of the negative balance of trade in recent times, however, it is likely that few people really understand much if anything about the system of international payments accounts from which it derives.

The tendency of the USA to have a negative balance of trade (more accurately known as a negative balance on current account) played a prominent role in the recent U.S. presidential campaign. Donald Trump criticized this tendency repeatedly and promised that if elected he would take various actions to reduce or eliminate it. Like most members of the public, Trump views this negative balance as a highly undesirable, economically damaging condition. Despite the prominence of discussions of the negative balance of trade in recent times, however, it is likely that few people really understand much if anything about the system of international payments accounts from which it derives. A new

A new

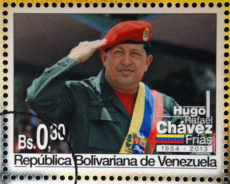

Venezuela’s dictatorship has tried to turn the fourth

Venezuela’s dictatorship has tried to turn the fourth  An interesting

An interesting  One of the zanier features of American politics is the Senate’s filibuster rule. Long ago, the Senate, by a simple majority vote, ruled that a supermajority is required to get any business done, with the result that often nothing gets done at all.

One of the zanier features of American politics is the Senate’s filibuster rule. Long ago, the Senate, by a simple majority vote, ruled that a supermajority is required to get any business done, with the result that often nothing gets done at all.