The Jim Crow Legacy of Southern Military Bases

The U.S. Congress passed a military defense spending bill with a veto proof majority in December. Yet, President Trump has vetoed the bill setting up a to-the-wire showdown with Congress. Trump’s objections included a provision in the bill to rename U.S. military bases honoring confederate generals. While Congress overrode Trump’s veto – its first – on New Year’s Day, the fact Trump and other Republicans considered base renaming initiative a political loyalty test is both significant and unfortunate. Yet, the so-called heritage critics of base renaming want to protect is probably not the heritage Republicans want to claim, unless they favor a return to Jim Crow America.

The main public objection to bases carrying the names of ex-confederates is that U.S. military bases shouldn’t be named after traitors. These are men who took up arms against the government. There is, however, perhaps a more sinister motivation behind the nomination of the particular generals at the time these bases were established.

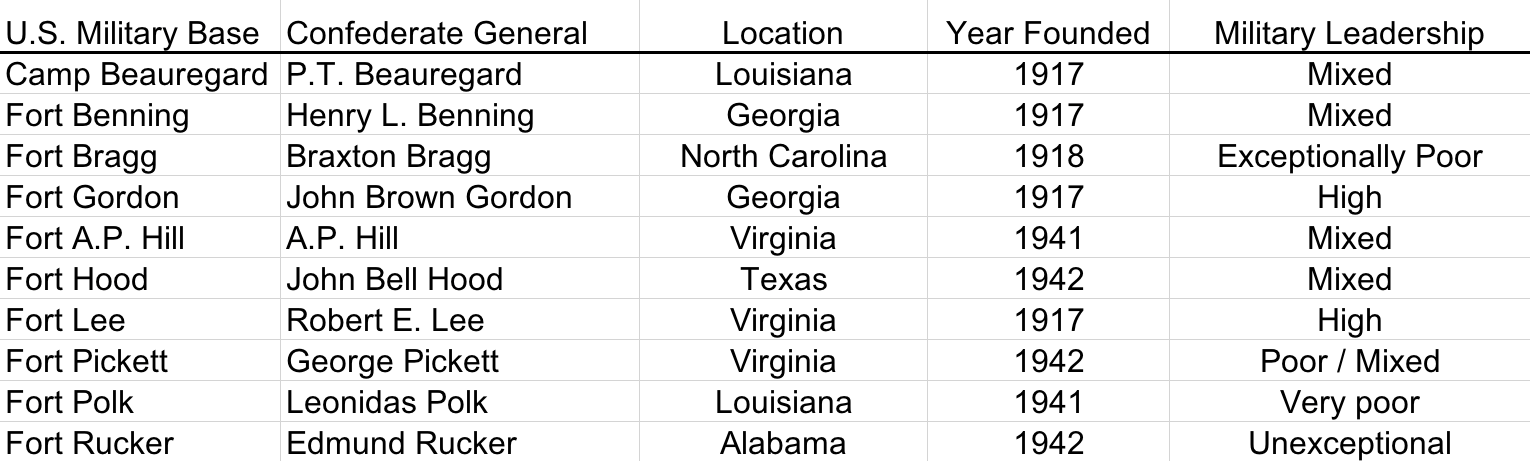

Currently, ten U.S. military bases, all in the Deep South, are named after ex-confederate generals: Camp Beauregard, Fort Benning, Fort Bragg, Fort Gordon, Fort A.P. Hill, Fort Hood, Fort Lee, Fort Pickett, Fort Polk, and Fort Rucker. But what qualifies these generals to rise above more than 380 brigadier generals, 88 major generals, 18 lieutenant generals, and five generals fighting for the southern cause?

Poor Military Record

Importantly, many confederate generals served with distinction in the U.S. military prior to the Civil War. Moreover, some of these officers were fighting for preserving state sovereignty, a core principle underlying federalism. Indeed, many at the time believed state sovereignty, including the slavery, was protected by the U.S. Constitution.

Notably, some Southern leaders, such as Robert E. Lee, widely regarded as one of the best generals in U.S. history, had reservations about the legality of secession. Lee ultimately turned down a commission in the U.S. Army to serve his native state of Virginia. While he owned slaves and a plantation – now the site of Arlington National Cemetary – Lee’s primary motivation to serve the South was loyalty to Virginia, He was not a dogmatic supporter of slavery or a slave economy.

But a closer look suggests Lee is the exception, not the rule. Of the current bases bearing the names of confederate officers, eight had undistinguished and occasionally exceptionally poor military records. In fact, three — Braxton Bragg, George Pickett, and Leonidas Polk — could even be rated incompetent. Others, such as John Bell Hood, were know for being reckless and ineffective, particularly later in the war. The others, excepting Lee and Georgia’s John Brown Gordon, have mixed records according to historians.

Why, then, would elected officials nominate these men to such a high profile and visible status?

Supporting Jim Crow

Keeping the rebellion alive as part of so-called southern heritage was one motivation. But the historical context in which these bases were named suggests something even more troubling.

The early and mid-twentieth century, when these bases were founded, was perhaps the apex of white supremacy as an ideology and tool of political oppression in the U.S. D.W. Griffith’s overtly racist movie Birth of a Nation was released to widespread commercial and critical success in 1915 in Atlanta. Americans voted an overtly racist Woodrow Wilson into the presidency in 1913 (with just 42% of the popular vote. Wilson subsequently unwound integration efforts under Republican presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taff, re-segregating federal agencies and employment. The Ku Klux Klan rose to national prominence in the 1920s, dramatically expanding its influence beyond the South and into the Midwest and Mountain States.

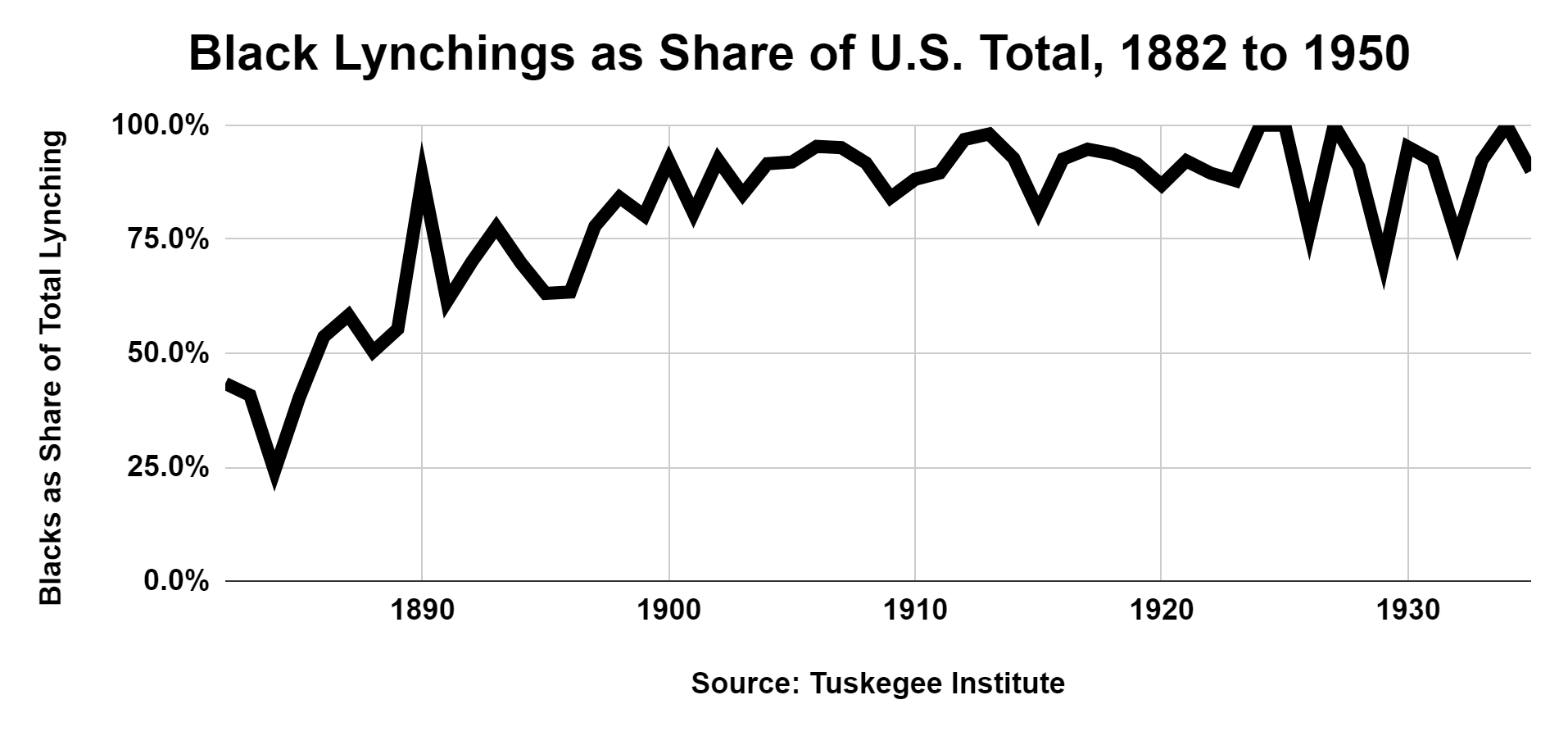

Lynchings evolved from being a unfortunately common form of mob justice applied to blacks and whites to a tool used almost exclusively against Blacks. While lynchings of whites dramatically declined after 1895, Blacks continued to experience this mob justice at high levels. From 1892 to 1900, Blacks made up 60% of lynchings. From 1901 to 1950, Blacks made up 92% of lynchings.

Since the end of Reconstruction in 1876, the South methodically and intentionally developed a system of oppression of Blacks. Naming prominent military bases after heroes of the Lost Cause was likely a calculated way to reinforce the hegemony of white supremacy . George Pickett, for example, is most known for “Pickett’s Charge” at Gettysburg and called the “high water mark of the Confederacy.” John Brown Gordon, while a good general, was also an ardent opponent of reconstruction and a likely member of the KKK.

This political strategy behind base naming likely had far reaching impacts. As the U.S. geared up for global wars in the twentieth century, hundreds of thousands of African Americans from around the nation would be trained at these facilities. Indeed, as Kareem Abdul Jabbar’s chronicles these threats in Brothers in Arms, an engaging history of distinguished 761st Tank Battalion in World War II. African American soldiers quickly learned that while the military might give lip service to equality, their lives were continuously in physical danger as they trained at these southern bases.

Indeed, famed baseball player Jackie Robinson, a Captain in the U.S. Army, was infamously court martialed at Fort Hood in Texas. A white bus driver had him arrested for not moving to the back seat of his bus despite army regulations requiring equal treatment. He was ultimately acquitted. But the racism embedded in the arrest and early findings against him was palpable. Murders of African Americans were not uncommon, and local authorities rarely felt the need to investigate let alone prosecute accused murderers.

Base Renaming is Long Overdue

The renaming of these military bases is long overdue. The ongoing attachment of these southern generals to American military history is problematic under the most charitable justifications. While history should not be erased, evil and injustice should also not be glorified. The principles under which those injustices were perpetrated should also not be given the honor of the symbolism inherent in the naming of U.S. military bases. Renaming these bases should be an easy lift.

See also on this blog,

- Five Recent Movies That Explores Race in America

- Marshall Spotlights Neglected Part of Civil Rights History

- Slavery and Justifications for Southern Secession in Their Own Words

- Should Gone With the Wind be Banned?

And these books from the Independent Institute:

- T.R.M. Howard: Doctor, Entrepreneur, Civil Rights Pioneer, by David T. Beito and Linda Royster Beito

- Race and Liberty in America, edited by Jonathan Bean