Review: Darkest Hour Probes Depths of Political Courage

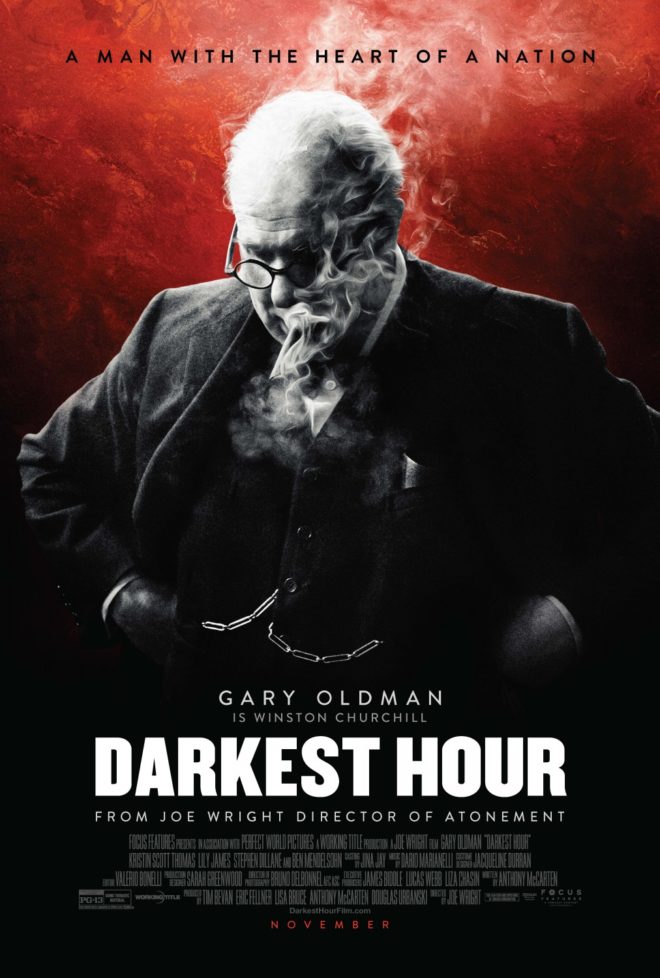

Darkest Hour probes the depths of political courage under overwhelming odds, focusing on the first few months of Winston Churchill‘s leadership as Prime Minister during World War II. The movie also presents a dilemma. On the one hand, Churchill experts have challenged the historical accuracy of several broad themes and characterizations (see here and here). On the other hand, the movie is excellent, in no small part to the stellar (and award-winning) performance of Gary Oldman (Harry Potter series, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes) in the role of Churchill.

Darkest Hour probes the depths of political courage under overwhelming odds, focusing on the first few months of Winston Churchill‘s leadership as Prime Minister during World War II. The movie also presents a dilemma. On the one hand, Churchill experts have challenged the historical accuracy of several broad themes and characterizations (see here and here). On the other hand, the movie is excellent, in no small part to the stellar (and award-winning) performance of Gary Oldman (Harry Potter series, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes) in the role of Churchill.

The specific events were real enough. Europe was collapsing under the weight of Hitler’s military in 1940, including the occupations of Poland, Denmark, and Norway . The diplomatic tactics of Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, The Time of Their Lives) had done little more than enable Hitler’s boldness, prompting him to resign as Prime Minister. Churchill is recommended by Parliament as the compromise candidate. No one else seemed acceptable to the major parties. At the time, Churchill was the First Lord of the Admiralty, the politically appointed head of the Royal Navy.

Churchill, however, carried a lot of political baggage. A staunch advocate for the British Empire, he resisted self-government in India. He supported the abdication of Edward VIII from the English throne. He carried the responsibility for the fall of Norway to German occupation. He still hadn’t shaken the political legacy of the disastrous military defeat at Gallipoli during World War I.

This context helps make Darkest Hour a compelling drama. After all, how did Churchill—the man who would become Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” in 1940 and 1949—navigate all this history and political baggage to emerge Prime Minister?

Darkest Hour provides very little background on this long, circuitous journey and instead starts with the decision by Chamberlain to step down. The preferred replacement was Edward Wood, Lord Halifax (Stephen Dillane, Zero Dark Thirty, Game of Thrones, The Hours), a member of Parliament’s House of Lords and foreign secretary. But he declined, and, in fact, believed Churchill was better suited by temperament to lead the nation in war. King George VI (Ben Mendelsohn, The Dark Knight Rises, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, Mississippi Grind)) reluctantly does his duty and appoints Churchill Prime Minister to form a new government. On May 10, 1940, the day Germany invaded France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, Churchill assumed his official duties as head of the the U.K. government. Churchill forms his War Cabinet and includes both Halifax and Chamberlain despite their dovish positions on the war.

The meat of the story surrounds Churchill’s leadership amid the tense infighting and virulent disagreements that brewed outside the public eye and within the War Cabinet. Britain’s top elected officials and generals sparred heatedly whether to sue for peace with Hitler, before it was too late, or continue fighting even though defeat seemed inevitable. Chamberlain and Halifax pushed for peace while Churchill stubbornly insisted on continuing the fight. Moreover, Churchill deliberately misleads the British public about the war’s progress to bolster public support. Churchill begins to waiver, however, as he rallies England for the evacuation of Dunkirk. He orders, against the advice of his War Cabinet, the annihilation of a section of the British Expeditionary Force trapped in Calais (France) as a diversionary tactic to aid the Dunkirk operation.

Darkest Hour, however, plays loose with history. Churchill advocates argue the movie does a disservice to the Prime Minister’s bold leadership and decisive decision making during what was the lowest point of the war. Indeed, historically, Churchill was supported by many precisely because his leadership skills were seen as essential for carrying out the war. The creative attempts to convey the emotional toll of the island nation facing its “darkest” hour may have the effect of undermining Churchill’s leadership role.

For example, the movie stages a scene in which Churchill, racked by doubt and uncertainty, escapes onto the London subway (the Underground) on his way make a major speech on the war to Parliament. As he interacts with common Londoners, he is emboldened by their resolve to continue the fight. The peace negotiations with Hitler are then projected as a compromise by political elites who, unlike Churchill, had lost faith in the English people. The entire scene is fabricated, and belies much of what is known, or at least commonly believed, about Churchill as a man and political leader. (Steven Hayward’s Churchill on Leadership: Executive Success in the Face of Adversity is an excellent, readable counterbalance to the movie’s fictional view of Churchill as Prime Minister.)

Nevertheless, the movie effectively conveys the desperation that gripped the United Kingdom under Hitler’s relentless advances, what appeared to be an inevitable invasion of Britain, and the shear isolation of the country as the U.S. failed to come to its aid. Gary Oldman’s performance is outstanding, as is the remainder of the cast including Kristin Scot Thomas (Sarah’s Key, I’ve Loved You So Long, Gosford Park) as his supportive but straightforward wife Clementine, Ben Mendelsohn as King George VI, and Lily James (Baby Driver, The Exception, Downton Abbey) as the secretary who receives the brunt of Churchill’s mercurial personality and enigmatic behavior.

Controversy and historical accuracy aside, Darkest Hour is a compelling reminder of the role courage and leadership play when facing overwhelming odds. Paired with 2017’s earlier contribution to this period of England’s history, Dunkirk, viewers may get a sense of just how close Europe was to complete capitulation to Hitler’s totalitarian vision for the continent. Fortunately, in this case, freedom won. Just remember: Darkest Hour is a narrative film, not a documentary.