Loving Exposes Dark Side of Legislating Morality

A small but important film is making its way through U.S. theaters this season, and its message will resonate powerfully with those favoring individual liberty and freedom. Loving has earned just $6.5 million at the box office, but the film tells a poignant story about an all too recent dark period in American history. The dangers inherent in giving government the authority to enforce moral codes like the ones addressed in this film are relevant today.

A small but important film is making its way through U.S. theaters this season, and its message will resonate powerfully with those favoring individual liberty and freedom. Loving has earned just $6.5 million at the box office, but the film tells a poignant story about an all too recent dark period in American history. The dangers inherent in giving government the authority to enforce moral codes like the ones addressed in this film are relevant today.

Loving follows the persecution and legal odyssey of Richard and Mildred Loving, the mixed-race couple that challenged Virginia’s miscegenation laws preventing whites and non-whites from marrying. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June 1967 that Virginia’s laws prohibiting marriage between races, and by extension all state laws, were unconstitutional. The state courts upheld the law on moral and religious grounds, claiming in its written judgement against the Lovings, “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents.... The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.” The U.S. Supreme Court struck down the law, arguing marriage is one of the “basic civil rights of man,” fundamental to human existence, and no government should prevent a man or woman from exercising this basic right.

Most U.S. states adopted laws banning interracial marriage at some point in our nation’s sordid history of race relations. Just nine states never adopted prohibitions: New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Alaska and Hawai’i. Pennsylvania was the first state to repeal its miscegenation laws, in 1780. The eugenics movement—the idea that public policy should be used to promote “superior” human characteristics—gave the movement a powerful boost in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, prompting states like Virginia to adopt even stricter laws. One legacy of these laws, of course, is the continued popular resistance to legal marriage by members of the LGBTQ communities. (Notably, 40 percent of Alabama citizens voted against taking the state’s miscegenation laws out of its state constitution when it went to a general vote in 2000, even though the U.S. Supreme Court made the provision unenforceable.)

Artistically, Loving represents a few interesting choices. Writer-director Jeff Nichols and the producers chose to make a small, intimate movie that eschews moralizing and platitudes to focus on the dignity of the relationship between the Lovings and their close relatives and friends. Even the attorneys that took their case to the Supreme Court are outsiders, in temperament as well as social acceptance. The film could easily have become a courtroom drama, a legal procedural, or at least courtroom centered. Instead, Nichols focuses almost exclusively on the courtship and then marriage of Richard (Joel Edgerton) and Mildred (Ruth Negga), using their innate stoicism and quite resolve as a dramatic foil to aggressive law enforcement and patently unjust state and local laws.

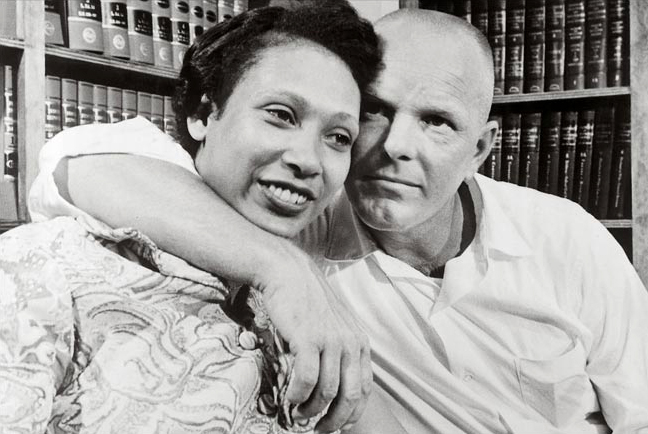

Mildred Jeter Loving and Richard Loving

The movie’s pace is slow and its soap boxes small and narrow, much in keeping with the humility of the Lovings and the rural areas in which they grew up and fell in love. The tone and aesthetic reinforces the point that the Lovings were ordinary people. They were not revolutionaries or rabble-rousers. Richard was a mason, laying bricks and concrete blocks on construction jobs during the day and tinkering with his cars in the back shed at night. Mildred stayed home and raised their three children. The dialogue is minimal, allowing their relationship to be shown through subtle, intimate action and expression. Richard and Mildred are a couple of few words despite an obvious commitment to each other. They internalize their sadness, anger, frustration and resentment; they don’t act out, allowing the setting and context to tell the story.

The film picks up in 1958. Richard and Mildred are already in love despite the disdain of local whites and the trepidation of relatives and friends. Knowing that interracial marriage was illegal in Virginia, Richard and Mildred elope to the District of Columbia. But they return to Virginia to live near friends and family. Mildred is pregnant with their first child when their home is raided by the local sheriff, tipped off by a local snitch. Both are jailed for cohabitation, although Richard is bailed out within hours because he is white while the pregnant Mildred is forced to wait until a judge is available the next week. At trial, the judge finds them guilty, sentencing them to a year in jail, but suspends their sentence if they agree to live outside of Virginia for 25 years. They agree, and move to Washington, D.C.

Nichols artfully orchestrates a series of scenes that highlight the catch-22 faced by families running afoul of these laws. When the Lovings are arrested, the local sheriff (Marton Csokas) challenges Richard about why he is sleeping with a black woman. Richard points to his Washington, D.C. marriage certificate, prompting the law enforcement officer to remind him that Virginia doesn’t recognize the license. Thus, they are not legally married, and therefore are cohabitating, breaking state law. Later in the film, their attorney reminds them that their children are legally considered bastards because their marriage is not recognized by the state. Since their children were born out of wedlock under Virginia law, the specter of the the state removing the Lovings’ children for morals justifications becomes all too real.

The Lovings’ case started to move forward after Mildred wrote a letter to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who forwarded their case to the ACLU. The ACLU assigned Bernard Cohen (Nick Kroll) and Philip Hirschkop (Jon Bass) to the case. While the film suggests that the ACLU single-handedly pursued the case to the Supreme Court, the Lovings were also supported by NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Japanese American Citizen League, and a coalition of Catholic bishops.

Loving is an artistic and cinematic tribute to the quiet heroism, faith, and virtue of the Lovings and common resistance to injustice. When Bernie Cohen asks if he would like to say anything to the U.S. Supreme Court justices hearing his case, Richard turns to him and uses a simple line that conveys the essence of the story and the fundamental injustice of their situation: “Tell the judge that I love my wife.”

Loving is also a welcome respite from the hard-driving action films that fill up the Holiday Season, and a fitting tribute to the importance of human dignity. The film, however, has a current relevance that should not be dismissed. Loving drives home the dangers of ceding moral authority to the state. Virginia’s legislators, law enforcement personnel, and judiciary justified the ban on interracial marriage on a misreading of Christianity that justified the prejudices of the times. Once these prejudices were ensconced in law, the police, courts and others could and did use these laws to terrorize citizens and further limit the rights and property of minorities.

Even now, most people in the United States don’t need to travel deep into their social circles to find friends and family who have been impacted by similar laws more recently. Members of the LGBTQ communities can testify to the indignity these laws reap, and how the fear of legal retrogression continues to cast shadows over their relationships, families, and hopes. This film serves as a stark reminder that these fears may not be irrational and, in fact, are grounded in reality and history.