As Regulators Fight Big Tech Mergers, Startups Often Pay the Price

Amazon announced on Jan. 29 that it would scrap its plans to acquire iRobot, maker of the popular vacuum Roomba. While a negative initial ruling on the merger from the European Commission in Nov. 2023 was likely the primary cause of Amazon walking away from a deal that had been valued at $1.7 billion in Aug. 2022, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reportedly also threatened action against the deal.

Vigorously opposing every acquisition by big tech companies, thereby raising expected costs and ultimately deterring acquisitions altogether, has been part of New Brandeisian crusaders’ “break up big tech” strategy since assuming control of the FTC and Department of Justice (DOJ). Amazon’s decision to not go forward with the iRobot deal when faced with a costly battle on both sides of the Atlantic led one FTC commissioner to promise further use of this “deterrence” strategy.

But the path taken by iRobot, which responded to the scuttled deal by laying off 350 employees and installing a new CEO, shows how the harm from reflexively challenging every merger involving big tech is disproportionately felt by the startups often seeking to be acquired. Worse still, this anti-merger approach might undermine future startups, and with them the kind of radical and disruptive innovation that may be big tech’s greatest competitive threat.

What would become iRobot was started by three colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s artificial intelligence lab. After developing military robots with a grant from the defense department, the company unveiled Roomba in 2002, right around the time it received multiple rounds of venture capital funding. The startup and venture capital model, while not unique to Silicon Valley, is such a crucial part of it that the two are commonly associated. The figure below shows that after an infamous 2000-era bubble, U.S. venture investment slowly became an established funding model (especially for tech startups).

Large, established corporations with research and development (R&D) labs and enough assets to bear some risk and upfront investment are often good at incremental or gradual technological change. But revolutionary or disruptive technological change is more likely to come from outside such big companies, a result confirmed across research in multiple fields and numerous anecdotes since the advent of the personal computer. Individuals, tinkerers, students, and, in the case of iRobot, academics often become entrepreneurs who light these sparks.

Startup innovators face funding constraints of a different magnitude than corporate R&D departments. Their disruptive work is even more uncertain, and its payoffs, if any, are even more likely to come only after long delays. Venture capitalists have played a crucial role in solving this mismatch between potentially game-changing but also highly uncertain and undeveloped ideas. They assume equity stakes in startup ventures, with an intended exit strategy usually either by an initial public offering (IPO) or private sale. Venture capitalists assume the risk over many projects knowing some—but not all—will be winners.

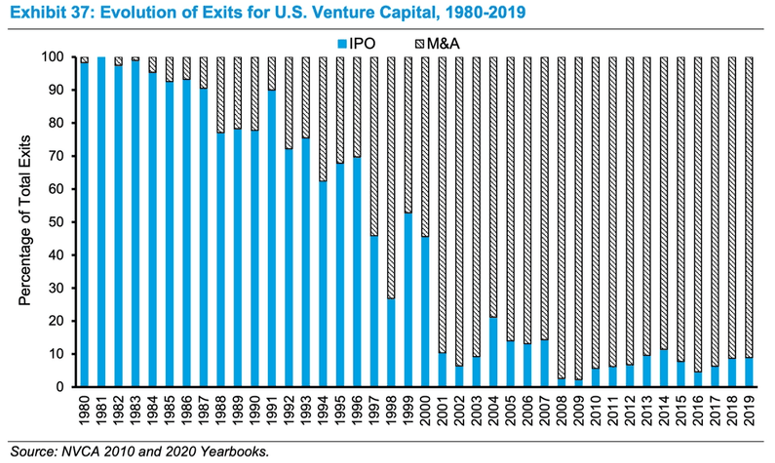

The venture capital model has thereby played a critical role in democratizing entrepreneurship, and merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions are critical to the venture capital model. Around the turn of the 21st century, digital and online startups started outnumbering businesses that provide products and services mostly in the physical world. As the figure below shows, successful exits for venture capital investments in startups went from overwhelmingly IPOs to overwhelmingly M&A.

(Source: Merusacap)

Many of these ultimate M&A transactions represent a startup with a unique capability of innovating along certain lines. Large companies, who may be able to distribute the technology more efficiently or create incremental improvements, seek to acquire such startups after successful venture capital funding has lessened uncertainty.

Similar reasoning from both parties seems to have been behind the now-abandoned iRobot deal with Amazon. iRobot initially bucked the trend shown above with a 2005 IPO and subsequently produced the market leader robotic home vacuums. But its layoffs and reshuffling at the top upon the merger’s termination suggest iRobot now saw value in being acquired.

These are, unfortunately, the types of M&A transactions upon which regulators have disproportionately directed their attention, such as Meta’s ultimately successful acquisition of VR fitness app maker Within. In the case of iRobot’s and Amazon’s abandoned deal, the response has been victory laps from European and American authorities (and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.)).

A reader more sympathetic to anti-big tech causes might respond that iRobot should keep going it alone with its already market-leading device or find merger partners other than today’s tech giants. But this misses the greatest source of harm from regulators’ fight against seemingly any tech merger. The developmental stages of a company like iRobot, injected early with venture funds under the expectation of lucrative future IPO and especially M&A markets, could face a highly damaging unraveling.

Among the greatest promises of our current explosion of technology are the countless examples of disruptive, ultimately lucrative innovation coming from garage tinkerers and any number of other non-traditional partnerships. If the left’s competition reformers create the lasting chilling effect on mergers they seek, they will likely make fewer venture capital deals possible, crowd the IPO market, and force poorly financed entrepreneurs to rush ideas to market.

Fewer innovative minds would be given the chance to bring to market the novel ideas they are uniquely positioned to have. R&D labs at big corporations could once again become the center of gravity for innovation in the United States, with all the limitations discussed above, not to mention fewer ideas being tested in the market.

Current U.S. and European authorities that believe they are restoring competition by deterring mergers and acquisitions may produce an even costlier chilling effect on innovation. In such a business climate, tech consumers would ultimately see less market competition, not more.

This article was originally featured on Reason.org. You can read the original here.