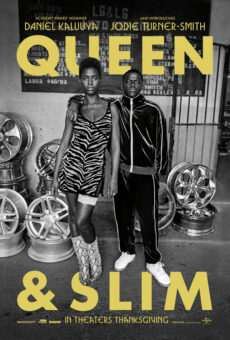

Queen and Slim’s Cynicism Should Prompt Serious Discourse on Race and Criminal Justice

When Queen and Slim went into wide release in November 2019, trailers suggested the movie was a story of a “black Bonnie and Clyde.” It’s not. That’s also the point.

When Queen and Slim went into wide release in November 2019, trailers suggested the movie was a story of a “black Bonnie and Clyde.” It’s not. That’s also the point.

The movie, directed by Melina Matsoukas and written by Lena Waithe, is a disturbing commentary on racial injustice in America. Most white and mainstream audiences will likely see little in the movie that connects to their experience. But it earned a respected sum at the box office: nearly $50 million at the box office, more than twice its production budget. And that’s a problem.

For non-black audiences skeptical of movements such as Black Lives Matter, or believe criticisms of law enforcement on race may be overblown, some context may be useful before watching the movie.

Consider recent events in Brunswick, Georgia. A father and his son, who were white, ran down a black man, Ahmaud Arbery, who was jogging in their neighborhood, and shot him. The police reports said the two men believed Arbery was a burglar because… he was a black man… running in their neighborhood… and wearing sweatpants. And a black man was seen in a house under construction in their neighborhood. They presumed a burglary was in progress. Hence, local prosecutors said the white men had probable cause to stop Arbery with their guns. (For those wanting details, columnist David French has a fair and accurate write up in The Dispatch.)

The white man and his son confronted Arbery by blocking him with their truck. They brandished a shotgun and a pistol and shotgun to force him to stop so they could “talk to him.” When the unarmed Arbery attempted to grab the shotgun, a tussle ensued. Arbery was shot and killed.

The prosecutors declined at first to charge the white men for reasons that, on their face, seem ludicrous: The white men were making a citizen’s arrest based on presumed knowledge that a burglary by a black man had happened in a their neighborhood. Then, they reasoned, when Arbery tried to take the shot gun out of their hands, the white men shot him in self defense. Even though the men initiated the stop and threatened Arbery with firearms, the unarmed Arbery apparently was a threat to the life of the white men.

(As someone who has jogged for more than 30 years in my neighborhood, I never had to worry about anyone trying to accost me with a gun under suspicion of burglarizing a house.)

The fears in the black community are real. They are backed up by evidence and experience. Consider the following quote, used with permission, from one of my social entrepreneurship seminars:

“As an African American, the recent attention around this phenomenon [of police brutality] impacted my life when my own dad told me not to keep my car’s registration and insurance information in the glove compartment anymore. His fear was that I would have to reach there at a traffic stop one day and a ‘startled’ cop may shoot me and give the explanation that they couldn’t see what I was reaching for. One reason that these cops (especially in the south) may shoot first and ask questions second is that there is often some explanation of probable cause or inside connection that protects the officer(s) from prosecution.”

Where are my — a white male — car registration and insurance information? My glove compartment. Where are similar documents for my children? In their glove compartments of their vehicles. Being white does have its privileges.

Academic research shows that blacks are more likely to be pulled over for traffic stops than whites. Unarmed blacks are two to three times as likely to be shot or killed by police officers, although the evidence of racial bias is mixed. (For a review of recent research and controversies, see these articles here and here at CityLab.)

For many in minority and poor communities, the strangling death of Eric Garner at the hands of New York City police over a minor street infraction, the shooting of 12-year old Tamir Rice because a Cleveland cop mistook his marked toy gun for a real one, the seven bullets used to kill Philando Castile in Minnesota as he was trying to comply with police commands — these incidents speak directly to their lives. In these victims, many if not most black Americans see themselves.

In this context, Queen and Slim represents an important if disturbing narrative. It speaks directly to a large segment of the minority community in America — one that distrusts law enforcement, is cynical about the criminal justice system, and no longer believes American institutions will protect them.

The premise underlying Waithe and Matsoukas’s story is plausible, even from a mainstream perspective. In Queen and Slim, an aggressive, possibly racist cop in Cleveland pulls over a black man because he is driving “erratically” (e.g., changing lanes without signalling, or crossing the line). The officer orders the driver, Slim (Daniel Kaluuya, Get Out, Black Panther), out of the car, and begins a search.

After finding dozens of boxes with what appear to be new shoes in the trunk, the cop pulls his gun and attempts to arrest Slim. Queen (Jodie Turner-Smith, The Last Ship, Nightlfyers), who is a jaded black defense attorney, gets out of the car and confronts the cop. She identifies herself as an attorney and announces she is getting her cell phone to call another attorney. The cop panics and shoots her in the leg. Slim lunges for the cop’s gun. They struggle, and Slim shoots the cop.

The scene is important and well crafted and an important set-up for the entire movie. Matsoukas’s direction makes the incident feel like a normal event, one that hundreds of black Americans experience every day across the nation. While most of these incidents do not end up with someone dead, too many do. The uncertainty surrounding the nature of the stop, the lack of clarity of the officer’s motives, and the vulnerability of the driver and passengers combine to create fear, frustration, and boiling anger. The scene has more than a few shades of incidents in Cleveland, Baltimore, New York City, St. Anthony (MN), Minneapolis, Tulsa, Baton Rouge, Portsmouth (VA), Wilmington (DE), Ferguson, and dozens of other cities.

Queen and Slim artfully captures the exasperation surrounding injustice after injustice in the aftermath of the unintentional and unfortunate death of the cop. Convinced they will not be treated fairly, Queen and Slim flee. They drive south, hoping to leave the U.S. and fly to Cuba. The drama, and their plight, becomes progressively darker as they dodge police during an interstate manhunt. Along the way, they take refuge among family and in black communities along the way. They become dubbed, much to their chagrin, “the black Bonnie and Clyde.”

The movie suffers from a few plot problems. Audiences may think, correctly, that a defense attorney would not recommend fleeing the scene of a murder. A seasoned attorney would not panic, even if she thought an effective defense would be an uphill battle. Queen and Slim also seem to travel thousands miles by car with almost no cash or access to credit. Slim spontaneously calls his father after being on the run for a few days, but somehow more than a half dozen investigators and cops happen to be in his father’s house when he calls.

But these implausibilities are beside the point. At worst, they are minor distractions in the context of the narrative. Each incident, except the final scene, is framed around a case that happened somewhere in America. What Waithe and Matsoukas do is tie the incidents together into a common thread.

The tragic ending is less outrageous when viewed as the logical consequence of a series of incidents that logically build to the end. The mindset that produces the movie’s climax seems all too real when we are faced with realities of actual racial disparities in perception. When an entire race (or class) of people is marginalized to the point that their lives (and livelihoods) are at risk even when they comply with the law, any hope for justice is fleeting and fanciful.

Notably, the real names of the lead characters are never revealed. The audience knows them because we privy to their private and intimate thoughts. To the outside world, Queen and Slim have no identity beyond how others project them. Circumstance and context does not matter. They are the black Bonnie and Clyde: Queen and Slim.

Despite its artistic weaknesses, Queen and Slim is an important movie, particularly now, in these times. The story resonates with many in poor and minority communities. But mainstream audiences, and the white community in particular, will benefit from this window into the defensiveness, anger, and frustrations bubbling up through minority communities. Queen and Slim can be the beginning of a very difficult but important dialogue. Black lives do matter.