What Star Trek Beyond Tells Us about the Luster of Naive “Progressivism”

Fifty years ago today, on September 8, 1966, the first regular episode of the path-breaking series Star Trek premiered on NBC television. Sold as “Wagon Train to the stars,” producer Gene Roddenberry delivered much more. His agenda included using the series as a vehicle for social commentary and to project a liberal, progressive, and utopian vision of the future—one built on equality, peace, freedom, cooperation, and unity under the benign watch of a quasi-military government—into the homes of millions of viewers each week. And on this score he was remarkably successful as the series grappled with racism, war, social justice, religion, beauty, technology, and many other issues of the day and future. The series also lasted just three seasons, suggesting its financial sustainability was weak and its audience limited.

Fifty years ago today, on September 8, 1966, the first regular episode of the path-breaking series Star Trek premiered on NBC television. Sold as “Wagon Train to the stars,” producer Gene Roddenberry delivered much more. His agenda included using the series as a vehicle for social commentary and to project a liberal, progressive, and utopian vision of the future—one built on equality, peace, freedom, cooperation, and unity under the benign watch of a quasi-military government—into the homes of millions of viewers each week. And on this score he was remarkably successful as the series grappled with racism, war, social justice, religion, beauty, technology, and many other issues of the day and future. The series also lasted just three seasons, suggesting its financial sustainability was weak and its audience limited.

Nevertheless, the idealism and optimism embedded in the original Star Trek gripped the imaginations of its fans. A short-lived animated series followed from 1973–74, and then a string of feature films beginning in 1979 led to the four independent television series: Next Generation (1987–94), Deep Space Nine (1993–99), Voyager (1995–2001), and Enterprise (2001–05). By 2016, 13 features made up Star Trek’s film canon. Combined, they have generated $2.2 billion in worldwide revenues on production budgets of $720 million. The cultural and commercial impact of the movie franchise is undeniable in 2016, despite the commercial precariousness of its first decade.

The films, however, have struggled among critics and peers. The first release, unimaginatively titled Star Trek: The Motion Picture, scored just 47% on Rotten Tomatoes, although this was higher than the embarrassingly low score of 21% give to The Final Frontier (1989). In fact, only two films—First Contact (1996) and Star Trek “reboot” (2009)—have earned more than 90% on the Rotten Tomatoes critics meter. None of the films has been nominated for major acting, direction, or screenwriting Academy Awards, and only one film has won an Oscar (for Best Makeup). This misfortune contrasts with the critical success of the original series, which was nominated for 11 Emmys and won three Hugo Awards, an NAACP Image Award, and a Best Original Teleplay from the Writers Guild of America. Subsequent Star Wars television series also won several awards, adding up to 31 Emmys for the entire TV franchise.

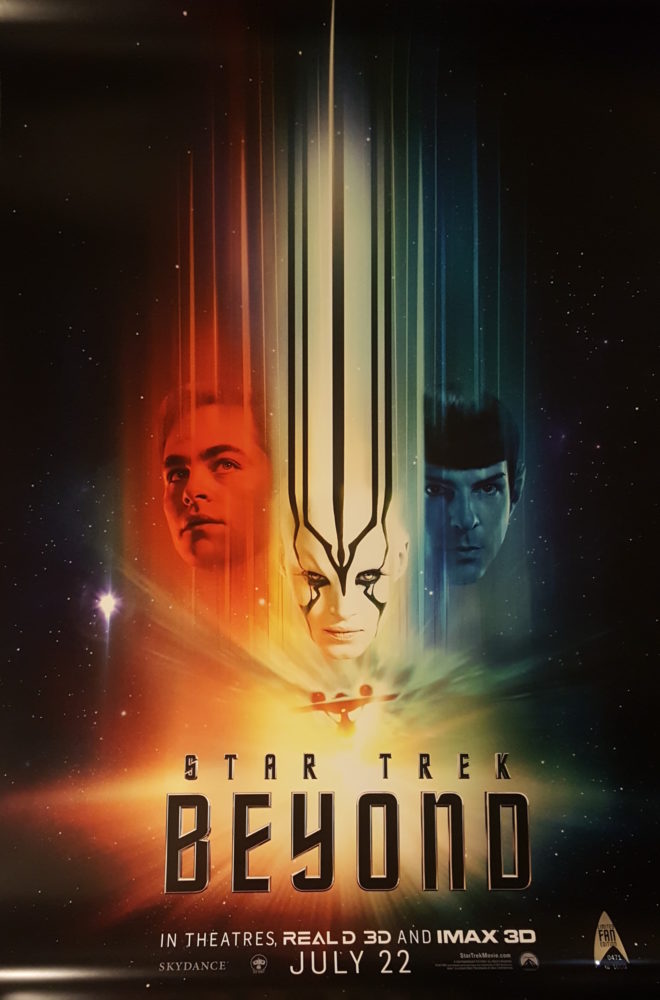

How does the most recent addition to the film canon, Star Trek: Beyond, fare? Not well, in my view. While critics have given it higher ratings than most of the films in the franchise, Beyond is unlikely to score Academy Awards or nominations. This is probably good for libertarians and liberty, although Roddenberry, who left earth for the final frontier in 1991, would likely have been disappointed.

Beyond is an entertaining romp through space, with far more action and adventure than social commentary. The film brings back the cast from Into Darkness (2013), the 13th film in the movie franchise and third in the so-called “reboot,” but it is directed by veteran action filmmaker Justin Lin, perhaps best known for directing the highest-grossing films in the Fast & the Furious franchise.

Beyond is supposed to invoke the artistic feel of the original television series, inspiring a sense of wonder and awe about space, its potential and danger. I think it succeeds on this level, using the plot device of a rescue mission to send the USS Enterprise and her crew to the edges of the universe. Well-crafted special effects, for example, combine with solid acting to provide a level of suspense that engages viewers as the starship makes its precarious way through a nebula.

Most of Beyond, however, relies on traditional action sequences and conventional plot devices, not dramatic tension between the characters. The movie is saved by solid acting rather than by clever, nuanced storylines. The Enterprise’s crew projects the noble unity and trust that Roddenberry envisioned in his idealistic world. (Such traits and behaviors are not unique to the Star Trek universe or Roddenberry’s vision; they are common during periods of intense group stress, when life-and-death decisions determine collective survival.)

The film hasn’t jettisoned the naive optimism or utopianism of the original series, but they are more of a backdrop than central to the conflict. The embedded political philosophy or liberal values don’t drive the plot or storyline. Indeed, the antagonist—Krall, a mutated human/alien creature—plays on screen more like a bitter, self-absorbed psychopath than a representative of a serious alternative world-view. In contrast, the Romulans and Klingons from the Star Trek of yore represented entire civilizations built on an alien Weltanschauung that directly clashed with the values of liberty, democracy, and equality that Roddenberry used to underpin the idealism of the United Federation of Planets.

The dialogue in Beyond attempts to draw out more substantive tensions between the values of unity, loyalty, and cooperation. Krall’s disillusionment with these values is crucial to his motivations, but they are not a threat to a social system. At risk are the lives of a deep-space starbase, not the United Federation of Planets. Krall’s drone fleet is undone by good old ingenuity, not the dogma of Roddenberry’s version of liberal progressivism. His goal of destroying the Federation plays more like a psychopath’s delusion than the reality of the threat he poses. Moviegoers empathize with the destruction of hundreds of thousands of innocents on the starbase, but the survival of the Federation is never really in doubt.

Beyond works within Roddenberry’s idealism but doesn’t push the boundaries far enough to keep the film from becoming a conventional, if solid, science fiction adventure. The Star Trek franchise seems to have lost its luster as social commentary, and this is probably for the better. The idea of a pan-universe system of governance modeled in the United Nations has been tested and found wanting practically since its founding.

Society has progressed along most of the social values that Roddenberry embraced when he scripted the original series, but not because a paternalistic, benign quasi-military government has carefully managed this transition. If the ideals that defined the counter-cultural themes of Star Trek half a century ago had became the lodestar to the modern films of the franchise, we would likely yawn and find it harder to enjoy a good sci-fi romp through the universe.