Price Controls: The Greatest Hits

That’s every economist’s reaction to renewed calls for price controls.

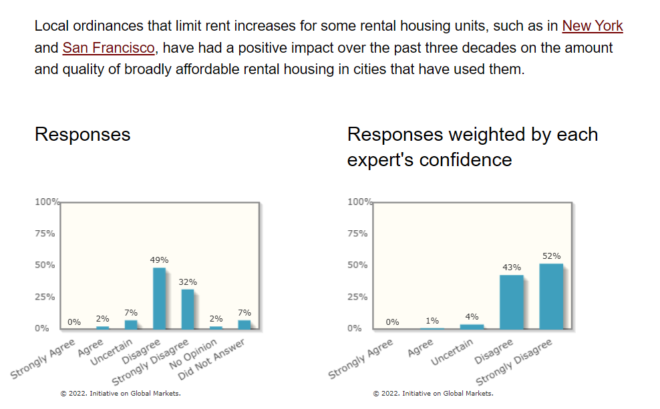

The theory is so airtight, the empirical evidence so overwhelming. The consensus among economists on price controls is impressive, and it stretches back decades.

What’s more, the assumptions required to oppose price controls are so minimal. Economics can’t tell you to favor prosperity and social harmony, but how many people truly don’t?

But I must confess: There’s one thing about price controls that I thoroughly enjoy. It’s the endless litany of colorful examples they provide for my Econ 101 course.

Price controls bring the “marvel of the market” into sharp relief. “See all this stuff that happens under price controls? Why doesn’t that represent your typical experience with markets?”

The answer is that markets are a continuous process of reconciliation among myriad buyers and sellers. Strange phenomena typically only emerge when something short-circuits that reconciliation process.

These are a few of my favorite instances of bizarre social phenomena. Many illustrations come from rent control because it yields such memorable stories, but the basic logic applies to any other price control.

Price controls don’t merely create shortages and surpluses—where Econ 101 too often stops. They redistribute income and they give rise to non-price mechanisms of resource allocation. Let’s look at each in turn.

- Redistribution

Price controls redistribute income and wealth between parties, often in unexpected ways.

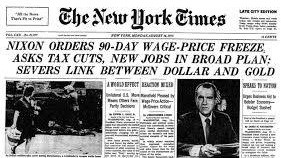

The infamous Nixon gasoline price controls, were implemented in August 1971. To keep rural gas station owners from being wiped out, the controls had not stipulated a nationwide maximum price but instead, prohibited gas stations from charging a price higher than the highest price a station had charged in May 1971.

Yoram Barzel brilliantly elucidates what followed. Gasoline is heterogeneous. There is low-octane gasoline and high-octane gasoline. Unsurprisingly, high-octane gas commands a higher price than low. Under Nixon’s price ceilings, sellers of high-octane gas began to replace it with low-octane gas. All the while, they kept charging the same price.

How was this the profit-maximizing strategy? Those with a high opportunity cost of time were willing to pay the high price for low-quality gas. After all, their alternative was to wait long hours in line for the same-quality gasoline at a marginally lower money price. Those who’d sold high-quality gasoline saw their costs fall (they didn’t have to buy the good stuff), while their revenues stayed the same, or even rose a little. In the end, the Nixon price controls redistributed income from low- to high-end gasoline sellers.

Price controls redistribute in more indirect ways too. Rent control, for instance, sometimes serves as a subsidy to wealthy city-dwellers. As Henry Hansmann notes in his underrated Ownership of Enterprise, “By driving down the rate of return on rented apartments, rent control creates a strong incentive for forming cooperatives and condominiums.”

Housing for the rich, which includes dwellings such as luxury apartments and condos, is typically exempt from rent control. Hansmann argues that rent control was an important influence in the spread of alternative housing options in post-WWII Western Europe. Other things equal, rent control is a handout to the rich.

- Non-Price Margins I: Quality

Yoram Barzel also argued that gas stations with a greater number of non-price margins of adjustment were more likely to survive the price-control onslaught than those with fewer.

Bizarre behavior under price controls stems from buyers and sellers adjusting the non-price margins. Quality and wait times are two of the most common non-price margins subject to change.

In a nod to the classic “Roofs or Ceilings?” essay, economist Steven Cheung explored non-price margins under Hong Kong rent control in a paper titled “Roofs or Stars? The Stated Intents and Actual Effects of a Rents Ordinance.” Stuck with a rent-controlled price, landlords will seek side-payments from prospective tenants who are looking to hop the queue. To provide these would-be tenants with a room, landlords must find a way to kick out existing tenants who are paying rent-controlled prices. Eviction without a cause was not a legal option.

Thus, landlords sought ways to make the lives of existing tenants miserable, so that they would leave “voluntarily.” Once gone, they were replaced by a new tenant who paid both the official rent control price and the under-the-table side-payment. To achieve these results, landlords in rent-controlled Hong Kong of the 1920’s would kindly remove windows from apartment units—during monsoon season. In short, landlords adjusted quality.

Rent control also removes the incentive for landlords to maintain their apartments. With a long line of people seeking housing, owners are less responsive to tenant demands. In extreme cases, landlords abandon the building altogether. When this happens, the structure can collapse. Economist Assar Lindbeck famously concluded that “In many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city—except for bombing.” For jarring visual evidence in support of this claim, see the classic 1981 book, “Rent Control: Myths and Realities.”

- Non-Price Margins II: Queuing

Every Econ 101 instructor describes the shortage that results from a binding price ceiling. Some stop short, however, of describing the colorful ways a shortage, or queue, plays itself out.

In a classic little essay aptly-titled “No Vacancies,” Bertrand de Jouvenel describes the housing situation in rent-controlled post-WWII Paris. Under shortage conditions, apartment units turn over quickly.

One consequence of this rapid turnover can be disturbing, even ghastly behavior.

Deaths are the only opportunity.

Young couples must live with in-laws, and the wife’s major activity consists in watching out for deaths. Tottering old people out to sun themselves in public gardens will be shadowed back to their flat by an eager young wife who will strike a bargain with the janitor, the concierge, so as to be first warned when the demise occurs and to be first in at the death. Other apartment-chasers have an understanding with funeral parlors.

De Jouvenel is being delicate here. In Paris, rent control generated stalker behavior. It also incentivized Coasian side payments from prospective tenants to undertakers. Not the sort of dignified behavior that contributes to social cohesion.

- Non-Price Margins III: Discrimination

Price controls lower the costs of discrimination, either by buyers or sellers. As we just saw, a binding price ceiling creates a queue. More people seek to buy the good than there are units of the good available. This allows sellers to pick and choose, sort and discriminate, between the buyers, selling only to those they prefer for some reason.

Usually, these dynamics are explored in the context of racial discrimination. But discrimination need not only manifest on the margin of race. In fact, any group that might generate higher costs for landlords are obvious targets of discrimination. Couples with children is one possibility.

As Edgar Olsen and Michael Walker write in Rent Control: Myths and Realities:

To the extent that they are unable to discriminate amongst tenants on the basis of price, landlords find it expedient to do so on the basis of race or other characteristics. Groups particularly vulnerable are those tenants that may cause higher costs for the landlord, such as large families or families with children (more “wear and tear” on housing unit) and people whose jobs require higher than average mobility (less stable tenancy).

Single people are, as a rule, lower maintenance risks than married couples for the simple reason that couples have children and children are messy. Faced with a choice between housing a single and a couple, landlords will more often choose single folks. Yet, landlords often don’t face that choice in a free market where prices adjust to clear the market of any shortage.

In the same book, Sven Rydenfelt likewise comments about the Swedish housing market:

Unmarried adults have increasingly been given the opportunity to invade the housing market and occupy a gradually increasing share of homes. At the same time, tens of thousands of families with children have been unable to find homes of their own.

Heavily squeezed between the demands of tenants for repairs on the one hand and reduced rental income due to rent control on the other, it is understandable that landlords in many cases showed a preference for single persons. Wear and tear, and thus repair costs, will usually be lower with single tenants than with families.

None of this is meant to suggest that each of these colorful and catastrophic consequences emerges in every instance of price control.

People aren’t prisoners of their environments. We can’t know for certain, ahead of time, which work-arounds will prevail in any instance. Human creativity is a constraint on the margins of adjustment. While it’s true that the particular circumstances of time and place will generate unique opportunities and constraints, one thing is certain.

After four millennia of observing price controls in action, we know to expect the unexpected as buyers and sellers devise clever, often unintended, solutions to their newfound circumstances.

***

This work originally appeared on Marginalia.