Vanderbilt, Stanford Rape Cases Show Need for New Approach to Campus Sexual Assault

Available on pre-order from Southern Yellow Pine Publishing.

On June 20, 2016, a jury convicted Vanderbilt University football player Brandon Vandenburg of rape after just 4 1/2 hours. He was found guilty on eight counts, meaning he could get 15-20 years in prison. Many are comparing the Vanderbilt case to the Stanford University rape case, where former collegiate swimmer Brock Turner was convicted of sexual assault with attempt to rape. But this is a mistake. The two cases are very different, and the implications for campus sexual assault policy are significant.

I’ve spent the last three years researching and writing a book on campus sexual assault, Unsafe on Any Campus? College Sexual Assault and What We Can Do About It, and it’s slated for official release on July 28th. This problem is enormously complex, and two important observations (among many others) became very apparent : 1) not all rapists are the same, and 2) the criminal justice system is poorly suited to address campus sexual assault.

The Vanderbilt and Stanford cases have several similarities: They occurred at what many would call elite universities,* they involved athletes, alcohol played a crucial role, and the victims were unconscious (or near unconscious) when they were attacked. One other factor puts these cases in a league of their own: the defendants were convicted of the underlying crime of sexual assault and rape. This happens in fewer than 10% of cases brought to prosecutors, a startling statistic I unpack in my book.

Here is where the similarities stop, and the implications for campus assault policy begin. The Vanderbilt case is a slam dunk for significant prison time. The jury agreed that Brandon Vandenburg raped his victim and orchestrated a gang rape that involved multiple levels of humiliation, degradation, and sexual assault. On an emotional level, the fact he did this to his girlfriend is hard for most people (including me) to comprehend. This case, from what I’ve read, has the marks of a predator. While I am not a therapist, the fact Vandenburg appeared so disinterested and removed from the welfare of the woman with whom he appeared to be emotionally and physically intimate at her most vulnerable state makes him appear sociopathic.

The case of Brock Turner, which I discussed in a previous article, is different. The trauma to the victim was severe—just read her victim impact statement. She describes the emotional and psychological anguish that many victims of rape and sexual assault experience (and is central to Chapters 2 and 3 in my book). While convicted of sexual assault with intent to rape, Turner was legally drunk, and his act was solo. His behavior and actions appear to be more characteristics of a naive, possibly entitled, freshman unable to differentiate between what was socially acceptable and what was not in the confusing world of today’s college campuses. While its still unclear whether he understands the gravity of the trauma he inflicted on his victim (based on his statement to the court), he has shown remorse to the court and taken responsibility for his actions. Turner’s assault, equally worthy of criminal conviction and its consequences, appears less intentional and more opportunistic. The difference is important.

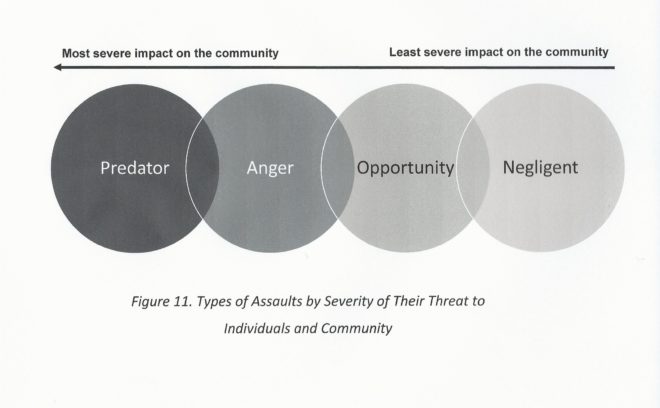

Source: “Unsafe on Any Campus: College Sexual Assault and What We Can Do About It,” p. 125.

In Unsafe on Any Campus?, I present an alternative way of looking at rapists and their impact on community welfare (Figure 12, page 125). I argue that campus sexual assault policy should recognize that rapists vary significantly in type and impact on the community. Predator rapists such as Vandenburg pose the most threat to individuals, their actions are the most destructive to community, are their cases are the most suitable for prosecution in the criminal justice system. They may well require isolation through incarceration to contain their impact.

On the other end of the spectrum are what I call “negligent” rapists. These are the teenagers who drink too much, don’t understand the practical meaning of consent, and make poor decisions that harm others (many seriously). The harm they inflict is unintentional, and a byproduct of other activities such as heavy partying. In between these ends of the spectrum are rapists impulsively motivated by anger and opportunity rapists who troll environments like bars and fraternity parties for naive targets. Each rapist need to be dealt with in different ways, although all need to be held accountable for the social and personal consequences of their actions.

Unfortunately, the legal system is incapable of differentiating between these types and what is necessary to prevent sexual assault and rape from recurring. The same adversarial criminal justice system is applied in all cases, regardless of whether the offender poses a threat to society. The potential consequences are also the same, irrespective of the circumstances and personalities involved. Turner could have been sentenced to up to 14 years in prison for one count of sexual assault with intent to rape. Vandenburg is facing 15-25 years for orchestrating a gang rape for eight counts including rape. Most observers want both defendants to receive the maximum sentence.

Few people, however, are asking the bigger question: what punishment is necessary to prevent sexual assault and rape from happening again? Incarceration presumes that the convicted offender is a continuing menace to society, a predator, a sociopath, unable to control physical urges. The only way to stop them is to isolate them from society.

It’s unclear that Turner fits this profile. Although recent evidence suggests he lied to the court about his background, lying is perjury and doesn’t qualify as sociopathic or lacks remorse for his actions. Based on the probation officer’s report and his own statements, he appears unlikely to commit sexual assault or rape again and realizes gravity of his actions (at least in terms of the law). While Turner should be held accountable for his actions, the benefit of jail time is unclear to him or the community. (If he becomes active in raising awareness about the trauma and human consequences of sexual assault, his work outside prison might be beneficial.)

Vandenburg’s case is more complex and alarming. The magnitude of his crimes and actions suggest he may well be a continuing threat to society. Almost certainly a “not guilty” verdict—the result of most sexual assault and rape trials—would have contributed to a sense of entitlement and trivialized the trauma he (and his peers) imposed.

Clamors for incarceration and lengthy jail sentences are often a reflection of frustration with a poorly functioning criminal justice system, anger at the human costs of sexual assault and rape, and a belief that harsh and severe punishment is the most effective solution to the problem. But this isn’t always the case.

For alternatives, perhaps we should look to the victim’s themselves. In the Brock Turner case, the victim said she didn’t want Turner to “rot in jail.” She wanted him to “get it.” Indeed, all indicators are that if Brock Turner “got it,” he would no longer be a threat. That’s the real goal, and it’s time to start looking for alternatives to the Incarceration State to achieve it and focusing the criminal justice system on the ongoing menaces to society.

*In an earlier version of of this article I mistakenly identified Vanderbilt University as a public institution. It is private. The text has been corrected to remove this error.