A Civil Society Agenda for Campus Sexual Assault

As studies refine our understanding of college sexual assault, more and more observers recognize that sexual assault and rape are serious problems on many campuses even if the scope isn’t large enough to be called an epidemic. In an academic year, a recent analysis completed for the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics covering nine colleges and universities found completed rapes may vary from 2% to 8% and sexual assaults may range from 4% to as high as 20%. These percentages, however, mask a lot of potential harm: at a large campus such as Florida State University, the low end of the estimates suggest hundreds of students experience rape each year. Of course, the expectation among parents (and students) is zero. College campuses are scrambling for solutions, begging the question: Does a pro-liberty/libertarian framework for reducing sexual assault on campuses exist?

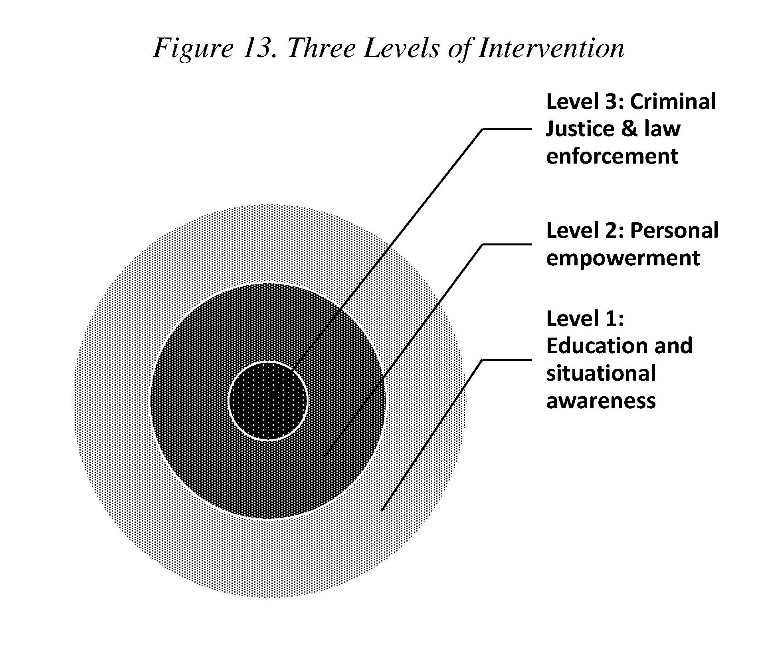

I believe the answer is “yes,” and libertarians and other freedom-oriented students and organizations should become more engaged as a result. In Unsafe On Any Campus? College Sexual Assault and What We Can Do About It, I scope out a three-level strategy for comprehensively addressing campus sexual assault. I actually narrow the scope of government and the criminal justice system while focusing solutions on voluntary individual action as the key to a broad-based solution that builds civil society and community.

Source: “Unsafe On Any Campus: College Sexual Assault and What We Can Do About It,” p. 136.

The criminal justice system shouldn’t (and as a practical matter can’t) be discarded, and this is my third level of intervention. When crimes are committed, especially when harm is created, the cases should be prosecuted and perpetrators should face penalties, including prison time. This is particularly important for predators, a class of offenders that require incarceration to stop their assaults. These are crimes against persons and property, and these offenses have traditionally been considered within the proper scope of the criminal justice system. The problem is that most campus sexual assaults are very difficult to prosecute successfully (an issue I devote three chapters to exploring).

So, sexual assault prevention policies need to rely primarily on risk reduction and prevention policies. These policies have an individual and a social component, but the key is to empower students to intervene to defend themselves or disrupt a potential assault on someone else (Level 2 in my framework). Personal empowerment has much more potential than most campus sexual assault prevention professionals recognize, but it’s crucial to the solution. For example, as just one example, recent research on Elemental self-defense system, a new comprehensive program designed specifically for campus environments by Ball State University sociologists Mellisa Holtzman and Chad Menning, has found reductions in exposure to sexual assault on campus (perhaps as high as 66%) for participants going through Elemental compared to control groups. (See also studies on self defense here and here.)

The other side of empowerment is bystander intervention, which is increasingly becoming a primary pillar in prevention efforts. Few cases have shown the importance of bystander engagement more clearly in than the Stanford rape case that claimed headlines earlier in 2016. A woman attended a fraternity party and admittedly made “bad decisions”—she consumed more alcohol than she realized and become severely drunk. (Notably, becoming drunk was not her intention or a goal of attending the party.) The perpetrator took advantage of her inebriated state and assaulted her. Two bystanders—Swedish graduate students—saw the assault and intervened, detaining the perpetrator while providing assistance to the victim.

While some bystanders will intervene on moral and ethical grounds alone, most need more tools. Thus, another goal of self-defense training is to facilitate bystander intervention. By training students in basic self-defense tactics, including verbal de-escalation and situational awareness, bystanders have tools that allow them to intervene more effectively when they see an assault occurring, or the circumstances emerging that might lead to one.

Educating students can also have surprisingly important benefits and influence behavior, and is Level 1 in my framework. When formerly acceptable behavior that can lead to sexual assault or rape is no longer acceptable, such as pressuring men and women to have sex when they don’t want to, using drinking games to lower someone’s resistance to sex, or ignoring a friend who puts date-rape drugs in someone’s drink, sexual assault is likely to decline. At Florida State University, education programs in place since 2010 have led to fewer men assuming that a woman’s decision to go a man’s apartment implicitly signaled she wanted to have sex, more men saying they would be likely to intervene if they saw someone pressuring a women to have sex, and men less likely to respect peers that engage in behavior that could lead to assault or rape.

All these strategies rely on reclaiming the essential importance of respecting and protecting human dignity at its core. These three levels of intervention—education, individual and bystander empowerment, and the strategic engagement by the criminal justice system—can inform a comprehensive strategy for addressing sexual assault while building civil society. After all, sexual assault and rape are fundamental attacks on individual human dignity and civil society.

Libertarian and conservatives have spent too much time on the policy sidelines of this important issue. While some have criticized Wendy McElroy’s recent attempt to address this issue in Rape Culture Hysteria, she at least engages in a constructive way on the policy side by addressing risk reduction and prevention. As one of the earliest individualist feminist writers, her recommendations shouldn’t be ignored in this debate.

But an overly narrow view of the problem and solutions risks doing too little when much more can be done. In a world in which less than 10% of sexual assault and rape cases brought to prosecutors end up with a conviction on the underlying sexual assault charge, and 90% or more of cases brought to prosecutors are grounded in a real event that created real trauma, the harm caused by sexual assault is simply too great to go unaddressed. We need strategies that build a virtuous community that respects and defends individual human dignity comprehensively.

Libertarians have a role to play in the debate over campus sexual assault, and it’s one that can help build civil society and a respect for individual human dignity into a cornerstone of campus culture.