The Plastic Bag Racket

Single-use plastic bag bans have been all the rage for the past 20 years or so, but, as is often the case with environmental laws, proponents have vastly overstated the benefits of doing so and understated the costs. It is another example where doing something is considered better than doing nothing—even if the results end up being more harmful in the end.

On a recent segment of “Jesse Watters Primetime” on Fox News Channel, host Jesse Watters decried the ways “reusable” bags are worse for the environment than “single-use” plastic bags and described such bans as a “cash grab” by grocery stores that profit from the sale of reusable bags. (The “single-use” designation was always a bit of a misnomer, as people tend to reuse these bags to line smaller trash cans, deposit pet poop, and hold or carry numerous other items.)

The segment referenced a March 2023 CNN.com article detailing various estimates of how many times reusable bags must be used to provide a greater net environmental benefit than single-use bags. These range from five to 52 times for polyethylene and polypropylene bags to many thousands of times for cotton bags, depending on how comprehensive the bag life-cycle analysis is (see this 2018 Danish government study, for example—scroll down for the English summary).

“There will always be cases where we forget our (reusable) bags at home,” Thomas Ekvall, adjunct professor at the Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden and one of the authors of a report comparing the environmental benefits of various bag types for the United Nations Environmental Programme, told CNN. “We should try not to do that but when we do, we need to buy a bag. And if we then have already too many durable bags at home, it would be better from a climate perspective, at least, to buy a single-use paper or plastic bag.”

I wrote about this issue back in 2013, just a year before California would become the first to impose a statewide ban on single-use plastic bags with the passage of Senate Bill 270 in 2014. (Plastic bag manufacturers succeeded in delaying the measure through a referendum, but in November 2016, Californians narrowly passed Proposition 67, thereby implementing SB 270, with 53 percent of the vote.)

In a column for the San Diego Union-Tribune, I discussed the often-ignored costs of alternatives to single-use plastic bags:

The claims that plastic bags are worse for the environment than paper bags or cotton reusable bags are dubious at best. In fact, compared to paper bags, plastic grocery bags produce fewer greenhouse gas emissions, require 70 percent less energy to make, generate 80 percent less waste, and utilize less than 4 percent of the amount of water needed to manufacture them. This makes sense because plastic bags are lighter and take up less space than paper bags.

Reusable bags come with their own set of problems. They, too, have a larger carbon footprint than plastic bags. Even more disconcerting are the findings of several studies that plastic bag bans lead to increased health problems due to food contamination from bacteria that remain in the reusable bags. A November 2012 statistical analysis by University of Pennsylvania law professor Jonathan Klick and George Mason University law professor and economist Joshua D. Wright found that San Francisco’s plastic bag ban in 2007 resulted in a subsequent spike in hospital emergency room visits due to E. coli, salmonella, and campylobacter-related intestinal infectious diseases. The authors conclude that the ban even accounts for several additional deaths in the city each year from such infections.

[Fun fact: This column was used by the College Board’s official SAT study guide to help test-takers analyze passages for the essay portion of the exam. See here (pp. 10-11), here, and here.]

In addition, I pointed out that banning or taxing single-use plastic bags only leads to increased demand for other types of bags: “This is just what happened in Ireland in 2002 when a 15 Euro cent (about $0.20 at the time, approximately $0.16 at current exchange rates) tax imposed on plastic shopping bags led to a 77 percent increase in the sale of plastic trash can liner bags.”

This is hardly a unique example. A recent Bloomberg article noted similar increases in other forms of plastic bags following California’s bag ban in 2016, New Jersey’s ban in 2022, and a 2011 ban in the Australian Capital Territory (where the capital of Canberra is located).

Similarly, an August 2023 Los Angeles Times article examined the failure of California’s plastic bag ban. Among its findings was that, according to data from the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle), the amount of plastic bag waste per capita has actually increased, from about eight pounds of plastic bags per person in 2004 to 11 pounds per person in 2021. In addition, it noted how plastic bags frequently gum up recycling machines. Even when placed in special plastic bag collection bins at grocery and retail stores, they usually end up in landfills anyway due to a lack of a market for the plastic and the dearth of recycling facilities equipped to recycle such materials.

The L.A. Times piece concluded:

Californians are generating more plastic bag waste per capita now than we were before the ban existed. Some shoppers are bringing reusable bags from home to stores, though not many, and far fewer are reusing HDPE bags they buy at the store. It’s unlikely that what goes into the store drop-off bins is being recycled. The “reusable” plastic bags we get from stores have become de facto single-use ones.

So what should be done about these “reusable” bags that are so difficult to recycle?

“Realistically,” the article offers, “the most efficient way to dispose of them is to use them as garbage can liners, pet poop bags, wet swimsuit holders, travel laundry hampers, and other household uses until they can’t be used anymore. Then put them in your trash.”

This is precisely what people did with the more environmentally friendly single-use bags before the ban!

Moreover, while reasonable attempts should, of course, be made to minimize litter, such as plastic waste making its way to waterways and oceans, the extent of plastic bag ocean litter coming from the United States has been wildly exaggerated by environmental groups, oftentimes with emotional pleas to save sea turtles and other marine life. As the Bloomberg piece explains:

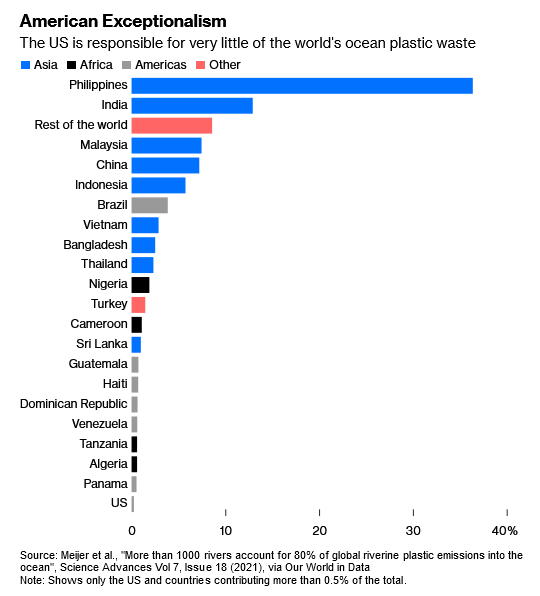

Hardly any of that detritus is attributable to the US, let alone New Jersey. Marine plastic mostly comes from short, fast-flowing rivers passing through large, middle-income cities that can’t afford to manage their waste properly. About 81% of ocean polymers come from Asia, with more than a third emitted by the Philippines alone, according to a 2021 analysis. The US, at 0.25% of the total, is generating less marine litter than Panama or the Dominican Republic.

Even data collected by supporters of New Jersey’s bag ban struggles to make it look worthwhile. A 2023 survey by the non-profit group Clean Ocean Action found that bags comprised less than 2% of the items picked up during beach clean-up days, with candy wrappers, bottle lids, cigarette filters, straws and stirrers and even cigar mouthpieces vastly outnumbering them.

It also offered this chart for comparison:

(And if all of that was not enough, it turns out that studies have now shown that the paper and bamboo straws to which people have been encouraged to switch actually contain toxic “forever chemicals” that make them worse for both the environment and those who use them. Thanks again, environmentalists!)

In any case, even if the plastic bag bans had been “effective,” that does not mean that it would necessarily make good or just policy. As I argued in the San Diego Union-Tribune piece,

environmentalists have every right to try to convince people to adopt certain beliefs or lifestyles, but they do not have the right to use government force to compel people to live the way they think best. In a free society, we are able to live our lives as we please, so long as we do not infringe upon the rights of others. That includes the right to make such fundamental decisions as ‘Paper or plastic?’

I would only add that it will become increasingly difficult for the most zealous disciples of the climate change religion—who tend to be less concerned about “the science” and actual results than perpetuating a dogmatic worldview that seeks to endlessly punish people for the purported sin of utilizing natural resources—to win more converts to their cause when their supposed solutions continually fail and needlessly impose costs on others.