“Worry About the Federal Deficit”

Worry About the Federal Deficit is the title of an article William Silber posted on LinkedIn several weeks ago. In it, the retired finance professor distills a lifetime of research and experience into a warning about the fiscal state of the U.S. government.

The Federal government is spending a lot more than it receives in taxes, so it is running a deficit that is financed by borrowing in the bond market. The size of the deficit relative to total domestic production (GDP), a rough measure of our ability to pay for our indebtedness, is about 6% in 2023. That percent has been higher in the past, during wars and recessions, but those episodes required deficit spending, and then the government returned to fiscal responsibility. Not so today. We are at full employment and not engaged in world conflict, so the 6% deficit is an unprecedented problem, especially since about 30% of our debt is held by foreigners.

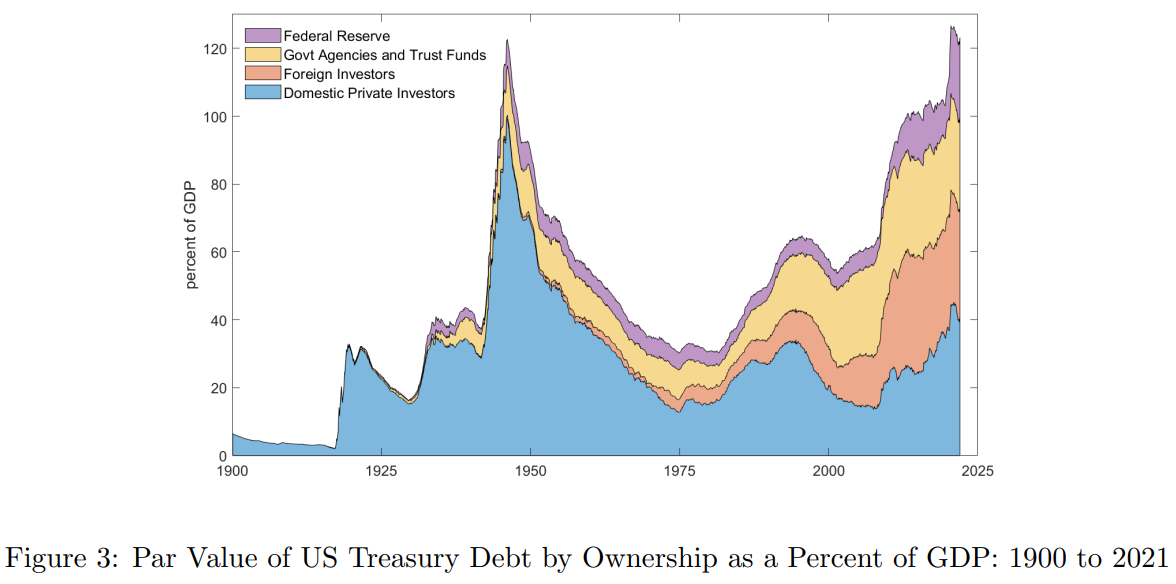

Silber points to the following chart from a 2022 paper on financing big U.S. federal expenditures by George Hall and Tom Sargent.

In this next section, he explains why that portion of the national debt represents a problem for today’s policymakers.

The fraction held by foreigners (shown in orange) remained small through the mid-1970s but has ballooned since 2000, and this is cause for concern on a number of levels. First, we can no longer claim the old refrain, “we owe the interest and principal to ourselves so the government debt does not burden our children.” China and Japan, the largest foreign holders of U.S. obligations, receive interest payments that will eventually require higher taxes, especially with the new era of high rates. The budget deficit will grow as current government bonds mature and are replaced with higher interest obligations.

Rolling over old national debt at today’s much higher interest rates is a major reason why paying interest on the national debt has become the fastest-growing category of government spending. In fact, the mere risk of that interest potentially not being paid as promised is why the U.S. government’s credit rating got downgraded.

Silber sees an additional threat arising from the U.S. government’s reliance on foreign interests in financing its excessive deficit spending.

Second, foreigners can stop investing in U.S. government debt whenever they please, and that would either drive down the value of the dollar in the foreign exchange market, raise U.S. interest rates, or both. Those unpleasant outcomes are unlikely to occur as long as the dollar remains international money, the world’s medium of exchange, but that needs a commitment to fiscal discipline. The pound sterling was once the world’s reserve currency but lost its “exorbitant privilege” to the American dollar during World War I as Britain turned from creditor nation to debtor. It is not easy to replace the established medium of exchange, but it has happened before. America should tighten its belt when it can, not when it has to.

Several countries are taking steps to reduce their need to use U.S. dollars in conducting their international business. How successful they may be remains to be seen, but they are motivated to pursue that goal.

Silber’s final point is absolutely valid. If fighting a fire completely drains your water reservoir, it would be the height of insanity to wait until the next fire is burning before taking any steps to refill it. The same principle holds true for the federal government’s fiscal policies.