Mr. Jones Makes Compelling Case for Scrappy, Robust Journalism

Perhaps one of the most overlooked movies of 2020 may be Mr. Jones. For those interested in freedom of the press and government accountability, this historical drama written by Andrea Chalupa and adroitly directed by Polish director Angieska Holland may be one of the most important movies in recent years. In chronicling the intrepid investigative reporting of Gareth Jones, the film makes a compelling case for scrappy, robust investigative journalism.

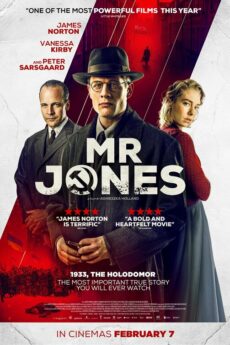

The movie follows the travails of Welsh journalist Gareth Jones (James Norton, Little Women, Flatliners). His skepticism leads him to unearth the gruesome details behind the Soviet Union’s false claims of progress in the early 1930s. What he uncovers, at great personal and professional risk, is the Soviet Union’s Great Famine, one of the 20th centuries great human tragedies. Some have even called it genocide. Notably, the famine is also called the Holodomor. In Ukranian, “Holodomor” means death or killing by hunger.

Gareth Jones’s Intrepid Reporting

Mr. Jones chronicles how how the Soviet Union’s Great Famine was uncovered to the world.

Jones’s journalistic profile rose dramatically when he snagged an interview with Adolph Hitler just as he became Chancellor of Germany. Nevertheless, as the movie opens, he works primarily as a foreign policy advisor to British Prime Minister David Lloyd George (Kenneth Cranham). Notably, Lloyd George was perhaps the last Liberal (re: libertarian) prime minister and a skeptic of the Soviet Union. Jones believes the Soviet Union is falling short of its economic objectives despite favorable press from Moscow. Jones secures permission to visit the Soviet Union by promising to interview Joseph Stalin.

While in Moscow, Jones meets and seeks the aid of New York Times bureau chief Walter Duranty (Peter Sarsgaard, The Magnificent Seven, Shattered Glass, Jarhead). Duranty, however, is sympathetic to Stalin and his efforts to industrialize and collectivize Russia and, most importantly, Ukraine. The Ukraine was the Soviet Union’s literal and figurative bread basket. He becomes more suspicious after receiving reports of hunger, which are validated by a young engineer working in Moscow (Vanessa Kirby, The Crown, Mission Impossible- Fallout, Everest).

Unable to get an interview with Stalin, Jones is in search of a story. He risks his life and reputation to travel to the Ukraine. What he sees would shock the world, if he could get out of the Soviet Union. But the Soviet Union, now seen as a potential ally, may help Europe counter the rise of Hitler in Germany. More importantly, Duranty’s Pulitzer Prize winning reporting on the Soviet Union had set the global narrative on Stalin’s progressive leadership and forward thinking economic policies.

Media Complicity Remains Relevant Today

What is remarkable about Jones’s story is the media’s intentional complicity in hiding a vast human tragedy. Yet Duranty’s political beliefs and personal support for Stalin’s dictatorship colored his reporting. In fact, Duranty believed Stalin was progressive. Russians, he thought, consistent with common Eugenics theories, were inherently “communal” and needed a strong central authority to organize them. Stalin, according to Duranty’s world view, was an “authentically Russian dictator.” Thus, he dismissed criticism from Jones and others. He actively and strongly challenged the facts on the ground.

In August 1933, months after Gareth Jones published his by-lined articles on the famine, Duranty wrote “Any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda.” The leftwing magazine The Nation described Druanty’s reporting as “the most enlightened, dispassionate dispatches from a great nation.”

Current estimates suggest up to 10 million ethnic Ukranians may have died during the Holodomor. Jones believed the causes of the famine were the forced collectivization of farms, redirecting grain to cities through state economic planning, and the purge of those in the private sector with agricultural expertise.

Sadly, Jones’s dogged reporting carried tremendous personal and professional consequences. He died at 29 years old, most likely at the hands of Soviet agents.

Modern Relevance of Mr. Jones.

Mr. Jones is a straightforward historical drama telling an important story. The movie is well directed and acted and faithful to the times and period.

Yet, Mr. Jones is more than a history lesson. It’s more than a biography. Rather, the movie raises important issues about how world views and political beliefs shape reporting and journalism.

These lessons are important to keep in mind as journalists report on a wide range of important issues, whether mass shootings or COVID-19 lockdowns.

Indeed, Mr. Jones, perhaps more than any movie in recent history, makes the case for a robust and diverse journalism industry to ensure the full story is told or at least accessible to the general public.