Mulan’s Subtle Subversion Withstands Beijing’s Censors

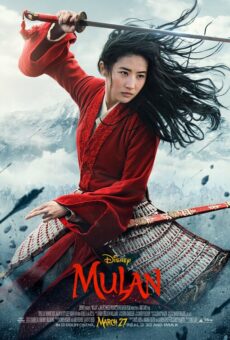

Last month, Disney launched the controversial and much anticipated live-action version of Mulan using its Disney Plus streaming platform. Many think the choice to stream the movie first rather than open in theaters will shake up the industry. And it might. After all, if families are willing to shell out $30 to watch a movie on Disney Plus, why go to a theater?

Artistically, the answer may be more complicated than many may think. This was a movie made for the big screen, not a small one, and it’s production values show it. A subtly subversive storyline also plays out as the movie attempts to bridge East and West while satisfying Chinese censors.

Made for the Big Screen

Disney Plus may well be saving the multimedia giant. Families sequestered in their homes by COVID-19 pushed the platform’s subscriber base to over 60 million within a year of its official launch.

Undoubtedly, Mulan helped Disney salvage some of its revenue for 2020. While revenues directly attributed to Mulan are unknown, the movie’s production budget of $200 million meant that taking a risk on its platform was better than waiting out the pandemic. A boycott organized by human rights activists, protesting the movie’s bowing to Chinese sensors, didn’t help its prospects either.

While this might be good for Disney in the short run, theaters are likely to remain important venues in the future. Mulan’s sweeping vistas, extraordinary visuals, well-scripted action scenes, and special effects are hard to appreciate on a small screen. This was a film made to be an event, not a cozy family escape.

The big loser in the shift to home theaters may be director Niki Caro. She delivers with the film’s high production values, smartly integrated but not overwhelming special effects, visual style, and adaptation from the legend. A New Zealander, Caro gained notice through the highly acclaimed but more modest movie Whale Rider (2002). Mulan is a much more ambitious project but also suits Caro’s storytelling instincts.

The most expensive film ever produced with a woman director at the helm, a lot was riding on the movie and its splash at the box office. (Previously, Patty Jenkins’ 2017 film Wonder Woman held the spot with a production budget of $150 million.)

Unfortunately, without the big screen, the weaknesses of Mulan’s story become more accentuated.

A Subtly Subversive Retelling

Mulan includes a cast of some of the most popular and respected Asian actors in the world. The tale itself is closer to the original legend. Mulan (Liu YiFei) is the daughter of Hua Zhou (Tzi Ma, The Farewell, Dante’s Peak, Rush Hour). Zhou established himself as a fierce and loyal warrior during previous battles in the Chinese emperor’s army.

Faced with Rouran incursions on the Empire’s northern borders – near modern day Mongolia — the Emperor (Jet Li, The Expendables film series, Kiss of the Dragon, Lethal Weapon 4) conscripts one man from each household to build a defensive army. Now, however, Hua Zhou is old. He is likely to be killed quickly. Mulan steps in disguised as his son.

But this version of Mulan also has a subversive, if subtle, story line. In the Chinese legend, women bring honor by fulfilling domestic duties. Men fight. This tradition is reinforced by the imperial government: The Emperor refuses to acknowledge the potential value of women as warriors.

This story turns on this central conflict. If Mulan takes her father’s place, despite her innate talents, she dishonors and shames her family. If she fails to be true to herself, she is condemned to misery. This tension is a defining element of the relationship between Mulan and her shape-shifting nemesis Xianniang (Gong Li, Farewell My Concubine, Coming Home, Curse of the Golden Flower).

Breaking from binding Chinese tradition, enforced by the hegemony of the Emperor, Mulan is a unique force with unique value that is essential to her being. Over the arc of the movie, Mulan must embrace, recognize, and channel her personal “qi” (chi), or life force. This inevitably draws her to become a gender-bending warrior. She must learn to embrace her own virtues and step into the traditional role of men. Ultimately, if she is recognized as a fierce warrior, she undermines the tradition while challenging the Emperor.

As in the well-known Chinese fable, Mulan successfully keeps her identity secret. Her warrior’s intuition develops as she grows up and finds her qi. In the live-action version, qi is closer to what many in the West might think of as “The Force” of Star Wars fame. This analogy is hard to ignore. Several mentors in the movie say, quite literally, that Mulan’s “qi is strong.” Without more cultural context, this dialogue rings hollow, a parroting of familiar lines with the Star Wars franchise.

Uninspired dialogue aside, this live action version of the tale remains a “coming of age” story in a very Western sense. This creative choice plays well with the movie’s target audience of families with young girls.

Keeping to Confucian Tradition

The live-action version explicitly bridges the traditional Chinese story of the Ballad of Mulan (by Guo Maoqian) with Disney’s animated version. Thus, the weight of the legend is more completely brought into the story. Sassy and snappy dialogue are left out, making room for a more earnest story line. The movie’s fantastical elements also seem more grounded to the legend.

Unfortunately, to keep the plot moving, the movie lops off connections in subplots and between characters. For example, we never see the consequences of Mulan’s dishonorable behavior for her family. Mulan’s relationship with her warrior comrades seems uncritical and superficial. The relationship between Mulan and Xianniang are one dimensional hero-villain … until it’s not.

Notably, the “virtues” of warriors etched into her father’s sword are Loyal, Brave, and True. But the story centers more around family than blind loyalty to the Emperor. Ultimately, the question becomes, who does Mulan pledge her loyalty to? On the surface, military service suggests the Emperor. In terms of the story, her loyalty remains with her family and the conflicts this creates through her choices.

Enter the Controversy

These story weaknesses may be attributable to script changes required by Chinese censors. The government aggressively uses access to the lucrative Chinese market as an inducement to discourage stories that might otherwise explicitly or implicitly criticize China or its government. In fact, Disney shared the script with the Chinese film board, and made substantive changes to the movie.

Government officials considered the animated movie’s emphasis on personal empowerment as too Western. Playing down obvious individualism in favor of Confucian tradition was one creative compromise. Another might have been an ambiguous historical setting that presents the Emperor as benign, although this would have been consistent with legend.

Heavy-handed shaping of stories from outsiders, whether they are governments or production companies, inevitably limits creative expression (hence the popularity of “director’s cuts” of many films).

Human rights activists organized a boycott to protest the film’s production in Xinjiang. This northwest province is home to Uighur Muslims who are experiencing brutal repression under the Chinese government’s crackdown on dissent. The explicit thanks and acknowledgement to China’s government for helping them make the film is particularly galling to many.

Bottom Line

The human rights violations by the Chinese government are real, disturbing, and worthy of condemnation. The validation of repression is an inevitable consequence of choosing to film in a country with a repressive government. At least the acknowledgements make this collaboration transparent.

Politics aside, Mulan is a worthy heroine for contemporary times for younger audiences. Ultimately, Mulan remains a well-produced, engaging, and largely western film that bridges East and West. The individualism embedded in honoring one’s qi, and how personal actions can benefit community and family, are honorable story lines.