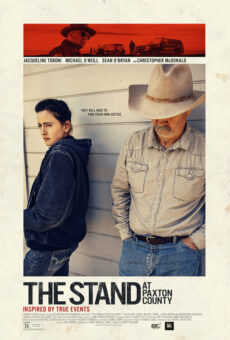

The Stand at Paxton County Puts Leftist Activism at Center of Corruption Drama

The Stand at Paxton County, an independently produced drama now streaming on Netflix, has a surprisingly straightforward message: Our freedoms and property rights are at risk when dogmatic special interests use the legislative process to achieve their goals. Moreover, poorly designed legislation opens the door to corruption.

The Stand at Paxton County, an independently produced drama now streaming on Netflix, has a surprisingly straightforward message: Our freedoms and property rights are at risk when dogmatic special interests use the legislative process to achieve their goals. Moreover, poorly designed legislation opens the door to corruption.

The movie, produced by Forrest Films (founded by entrepreneurs Forrest and Charlotte Lucas), does something else unusual for contemporary films: It raises awareness and makes relevant the plight of ranchers and farmers under a gun from political activists. Many of these advocates know little, or don’t seem to care, about this industry, its culture, and its values.

While a few think tanks and other nonprofits work on these issues — the Mountain States Legal Foundation and Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), to name two — contemporary filmmakers largely ignore the political threats to the modern small farm. As a result, even well-meaning activists tend to misinterpret, or misunderstand, the nature of agricultural businesses and family-owned enterprises that work on or beyond the urban fringe.

The story underlying The Stand, inspired by a real event, centers on a family’s attempt to save its farm from corrupt public officials in South Dakota. Dell Connelly (Michael O’Neill, Messiah, Scandal), an aging and ailing ranch owner, is coming out of a particularly brutal winter. His horses and livestock are the bread and butter of his operations. His horses are skinny and, to the naked eye, look malnourished. Connelly and other ranchers know that this condition is cyclical and that their horses will soon return to a healthy weight.

A new state law, however, allows anyone to claim animal abuse, triggering an investigation by a local veterinarian (Marwa Bernstein). Connelly’s livelihood, and the family farm, are threatened when the vet declares his horses unfit and abused, and the local sheriff (Christopher McDonald, Ballers, Real Bros of Simi Valley) seizes his livestock.

All of this is suspicious to Connelly’s estranged daughter Janna (Jacqueline Toboni, The L Word, Grimm), an army combat medic summoned home when her father becomes gravely ill. She sees that the ranch has fallen into disrepair despite her father’s hiring of a full-time ranch hand. Nevertheless, the horses, including her favorite, seem healthy if a bit thin from the winter. She begins to investigate. Soon, Janna suspects the long-time sheriff is hiding something, and may be in collusion with a local veterinarian.

The Stand is surprisingly engaging despite its use of well-trodden themes. Corrupt law enforcement figures, particularly sheriffs, are a staple of the traditional westerns and modern thrillers (e.g., Unforgiven, Rambo: First Blood, Young Guns, just to name a few). The estranged child returning to find their roots is also so familiar it’s cliché. But Toboni’s portrayal of the daughter, pushed away then reluctantly pulled back by family obligations, is convincing.

The twist that The Stand brings to the screen is its explicit tie-on to state level politics and the local corruption it engenders. Fortunately, the plot follows a more conventional thriller line, bringing the audience along as Janna unearths clues to the corruption even as it puts her life at risk. Thus, the audience engages through the drama rather than a lecture on politics. While the plot and the climax are predictable, the twists and setting are sufficiently different that audiences are likely to stay focused and in the story.

The sheriff and the veterinarian are not nuanced characters, but given the genre and film tradition, most audiences won’t stumble on these tropes. Janna’s journey from estranged child driven away by a difficult father to later appreciate the values, hard work, and simplicity of ranch life is well scripted and convincing. The movie also wrestles effectively with the tension between a population increasingly distant from its agrarian legacy, and largely ignorant of its practices, and those who remain committed to the lifestyle and business.

The Stand is most likely to lose its audience when it fails to give dimension to the animal rights activists. The advocates are caricatures, equating them to the greed of the sheriff and vet. The failure to give these characters more complexity limits the movie’s ability to elevate the story and broaden its appeal to general audiences.

Nevertheless, The Stand at Paxton County is entertaining and a welcome entry into an emerging genre (now dominated by progressives) of films crafted to entertain and raise awareness about social-justice issues. In this case, the injustice is meted out against ranchers and farmers. The movie and Forrest Films deserves praise for addressing this little understood or recognized problem in rural America even if it might stumble in reaching a truly broad audience.