Government Is Failing to Fix Homelessness with Housing

What if your city government spent millions more than it does today to pay for housing for the homeless? What do you think your community would have to show for it?

In San Francisco, the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH) has taken on the task of housing many of the city’s homeless residents. In 2020, the HSH spent $600 million to provide services and housing for the city’s homeless residents. That’s an increase of nearly 65% from its 2019 budget, so the HSH has lots more money to spend to house the homeless.

And spend it does! Most notably, the HSH dedicates $160 million through its Permanent Supportive Housing program to pay for homeless residents to live in the city’s 70 Single-Room-Occupancy (SRO) hotels. So, mission accomplished, right?

Perhaps not, as we’re about to find out.

When Housing Fails to Fix Homelessness

The HSH commissioned a study that monitored what happened with 515 homeless residents it supported in SRO hotels during 2020. The study found a stunning lack of positive results for all the money spent by the HSH to house the homeless. The San Francisco Chronicle‘s Joaquin Palomino and Trisha Thadani describe what happened to the homeless residents the city tracked:

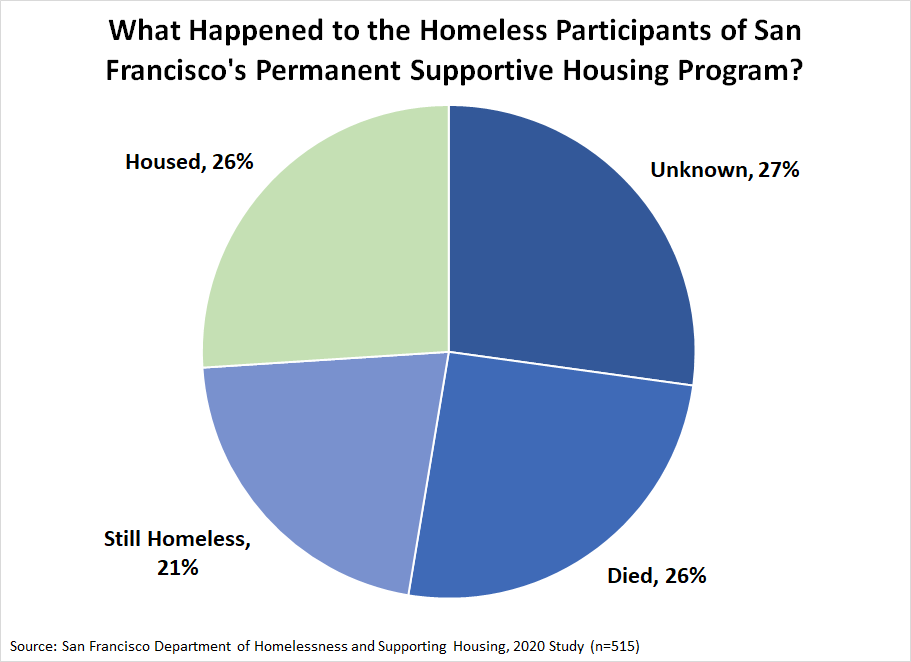

HSH says its goal is to provide some residents with enough stability to enter more independent housing. But of the 515 tenants tracked by the government after they left permanent supportive housing in 2020, a quarter died while in the program — exiting by passing away, city data shows. An additional 21% returned to homelessness, and 27% left for an “unknown destination.” Only about a quarter found stable homes, mostly by moving in with friends or family or into another taxpayer-subsidized building.

Here’s what those results look like when presented in a pie chart:

These results confirm the HSH’s Permanent Supportive Housing program failed to achieve its goals. What it achieved was neither permanent, nor supportive, nor successful in housing the vast majority of San Francisco’s homeless residents who participated in it.

What’s Going Wrong?

To put it bluntly, San Francisco’s government bureaucrats are choosing to ignore the problems with people that made them homeless. Instead, they’re trying to fix them with subsidized housing.

The SROs are clustered in and around the Tenderloin, a neighborhood riddled with so much crime and open drug use that Breed in December declared a 90-day state of emergency there. By allowing people to live in such conditions, San Francisco has spent hundreds of millions of dollars but still failed to help those most in need — and only hindered its efforts to tackle the ever-worsening homelessness crisis.

“We’re shooting ourselves in the foot,” said Margot Kushel, a UCSF researcher and national authority on best practices in supportive housing. “We can’t (house) people who are incredibly high-risk and not give them the services they need. It will not work.”

There are real consequences because of the bureaucrats’ failure. Six thousand homeless residents being housed in the city’s SRO hotels live in a climate that’s getting worse.

A Misguided Bureaucratic Vision

At the core of what’s going wrong with San Francisco’s Permanent Supportive Housing program is the misguided philosophy behind it. City Journal’s Erica Sandberg explains:

This is Housing First policy in action. The idea behind it is as simple as it is misguided: Put people who were living outside or who are at risk of becoming homeless inside four walls. Then, voilà, you’ve solved the problem of homelessness. It’s not true, of course. More people arrive in San Francisco every day, most seeking the city’s cheap narcotics and easygoing attitude toward usage. They end up on the street until they can score subsidized housing.

Stuffing thousands of people who should be recovering in hospitals, mental-health facilities, and drug-treatment centers into free or low-cost apartments has been disastrous. The places in which they are housed are ruined; people get hurt, and some die. Neighborhoods fall into disorder.

The dilapidated state of SROs is only a symptom of the disease. Housing isn’t a cure. Unless cities address the underlying problem of untreated mental illness and addiction, every building set aside for the homeless under the Housing First approach will deteriorate, and the people desperately needing help won’t get it.

It could be several times worse. But then, we would be talking about Los Angeles’ homelessness crisis. But that’s another story for another day.

To learn more about the humanitarian crisis of homelessness in California, see Independent Institute’s policy report Beyond Homeless: Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes, Transformative Solutions.