Shortfalls in Funding State Government Employee Pensions

Many state government-run pension plans are running short of the money needed to pay 100% of the retirement benefits that state politicians have promised to the teachers, police officers, firefighters, and other employees of state governments.

How short depends on the state and how you measure the amount of the shortfall. In October 2018, Bloomberg‘s Danielle Moran tallied the total liabilities and the funded portion that applies to each state’s public employee pension funds, finding that five states had funded less than 50% of the cost needed to pay for their promised state public employee’s pension benefits:

- Kentucky (33.9%)

- New Jersey (35.8%)

- Illinois (38.4%)

- Connecticut (43.8%)

- Colorado (47.1%)

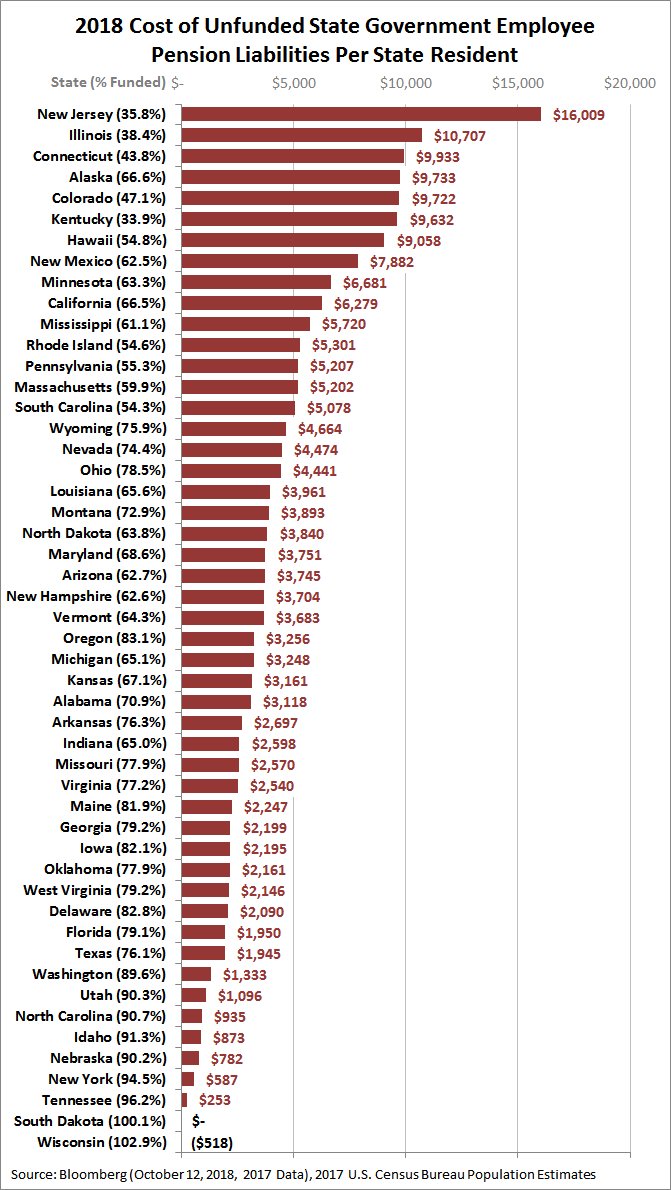

Another way to measure the shortfall is to calculate the amount of money that each individual state resident would have to cough up to fully fund the cost of providing state government employees with the retirement benefits promised to them by state politicians. The chart below shows those figures as calculated from the 2018 pension funding data provided by Bloomberg and state population data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The dollar amounts shown are how much every man, woman, and child in each state would have to pay today to put each state public employee pension fund on track to pay out promised benefits to state government workers in full after they retire.

The residents of two states have good news. Both Wisconsin and South Dakota have fully funded their state employee pensions, where Wisconsin has actually overfunded it by $518 per state resident.

Unfortunately, 48 other states would require each of their residents to pay more out of their pocket to cover their unfunded public employee pension liabilities. Going by this measure, the five states worst off include:

- New Jersey ($16,009)

- Illinois ($10,707)

- Connecticut ($9,933)

- Alaska ($9,733)

- Colorado ($9,722)

Kentucky’s 4.4 million residents, which ranked the worst by its percentage of pension liability that has been funded, would have to each come up with $9,632 to fully fund their state government employees’ pensions.

Worse, those costs can be expected to rise since politicians in the state’s legislature failed to reach a compromise to resolve the state’s pension crisis in a special session at the end of 2018, where at least one of the state’s largest public employee pension funds is projected to run out of money and collapse within five years.

Truly fixing the problem will mean resetting the level of state government employee pension benefits to fiscally sustainable levels, which state government employees have so far successfully resisted.