Snowden Spotlights Dangers of Privacy-Security Trade-Off

Few figures have been as polarizing as Edward Snowden, the intelligence-agency computer contractor turned whistleblower who leaked national security files to the press and raised global awareness about the breadth of U.S. government spying. Snowden has been in effective exile since 2013, when the government revoked his passport and started pressuring Russia to extradite him to the United States to stand trial for treason and other crimes. He is hailed as a hero in libertarian circles—see this clip from Reason TV on the efforts to promote a pardon—and by others favoring strong protections for civil liberties and privacy.

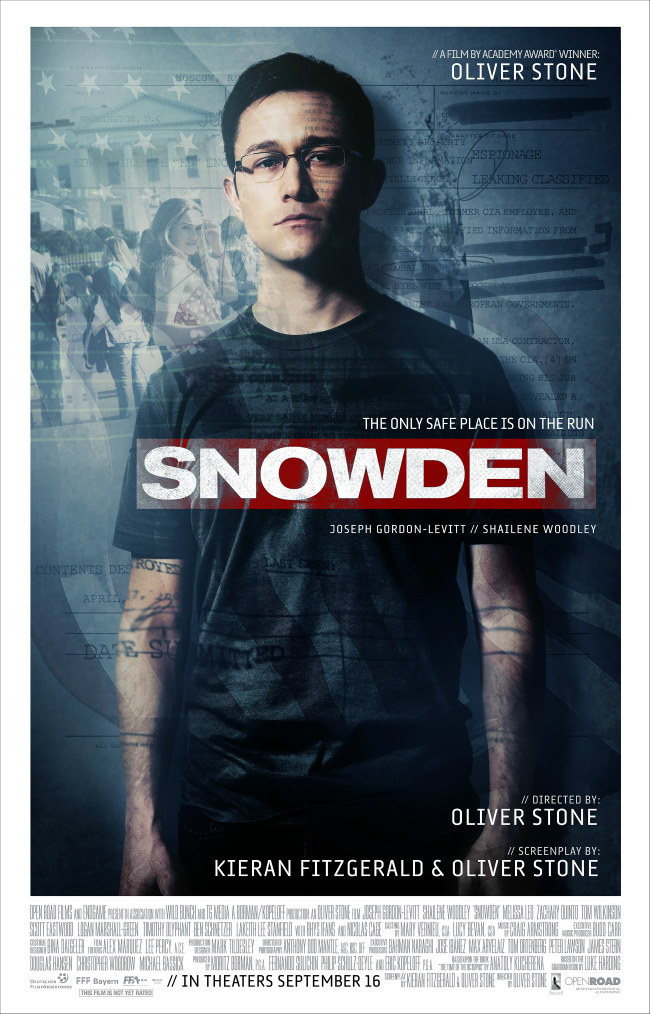

Given Snowden’s impact, a film about him and his actions was inevitable. The real questions were: who would be responsible for making it, and what story would it tell? We now have the answer in the biopic Snowden, directed by Oliver Stone and based on two books, one by a journalist and the other by a Russian attorney who represented the whistleblower. The story unfolds in flashback as Snowden (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is interviewed by award-winning documentarian Laura Poitras (Melissa Leo) and journalist Glenn Greenwald (Zachary Quinto) in Hong Kong in 2013.

What unfolds is a somewhat plodding film that is underwhelming as a “political thriller,” its advertised genre. The pace never really builds, and the artistic commitment to faithfully tell the story of Snowden’s ideological drift, from conservative patriot to hardened government skeptic, creates a straight-line narrative that lacks dramatic conflict and tension. The primary suspense involves Snowden’s unsteady relationship with his girlfriend Lindsay Mills (Shailene Woodley), not his personal journey toward surveillance skepticism and his decision to go public with classified information that ultimately upends global relationships. As a biopic, however, Stone’s film crafts an effective chronicle of Snowden’s transformation from a naive army Special Forces recruit to a values-driven surveillance skeptic.

Oliver Stone, of course, is known for making historical narrative films that blur lines between fact and fiction, such as JFK (1991), The Doors (1991), and Nixon (1995). He is also an accomplished documentarian of films that spotlight leftist and progressive political figures such as Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales (Bolivia), Rafael Correa (Ecuador), and others, many of whom he praises. Many of his other narrative films carry strong anti-war themes, including Platoon (1986) and Born on the Fourth of the July (1989), both of which won him an Oscar for Best Director. Unfortunately, Stone’s skepticism of government appears directed primarily at capitalist democracies, not left-wing or progressive governments with dismal records on civil liberties and personal freedom.

Given his leftist leanings, I was surprised by the restraint of Snowden (the film) on many of these issues. In part, this may be because Stone is profiling someone whose life’s calling focuses on the duplicity and anti–civil libertarian underbelly of the modern American Security State. The film has its antiwar and anti-military moments, but for the most part it stays focused on the main theme—the ethics and practice of warrantless government surveillance of unsuspecting American citizens without reasonable suspicion of unlawful activity.

The film does a good job of laying out the tension between privacy and security. At one point, Snowden’s CIA mentor makes this conflict explicit, rationalizing mass surveillance on the basis that people want security more than privacy and that secret surveillance is crucial to providing security. Meanwhile, Snowden’s disillusionment deepens as he sees the government making public claims that contradict its actual behavior. He begins to see how, in his own work, he has aided and abetted privacy violations that willfully ignore promises of transparency and public accountability. Snowden’s story is one of disillusionment that ultimately prompts action. But none of this is news. This is the public narrative that has described Snowden’s behavior ever since he came out as a whistleblower in June of 2013.

Perhaps this familiarity is why the film’s main tension settles on Snowden’s relationship with his girlfriend, Lindsay Mills. Their commitment to each other is central to the film, providing emotion to a bland story, and their breakups and reunions reflect the tensions implicit in jobs that isolate individuals from society more generally. By virtue of his status as a security contractor, Snowden becomes withdrawn and isolated from Mills. Their relationship falls apart even though Mills is credited with triggering Snowden’s skepticism about the power of the State. Ultimately, their parting reflects the collateral damage that comes with employment in an industry driven by blurred ethics, and where secrecy and obfuscation are accepted strategies for achieving success.

In the end, I found the film’s pace weighed down by its focus on the intellectual transformation of a lead character who lacks charisma and the kind of brooding that can build to an explosive climax. The decision to actually go public with classified information is never really in doubt. The question is when. Since most of the audience know the outcome—virtually nothing new is revealed, the story has a linear trajectory with few twists, and the character’s heroism is internal rather than external—viewers are likely to feel every minute of the 2 hour, 14 minute film.

Nevertheless, libertarians and skeptics of centralized government authority will likely find the film worth seeing. The movie appears to be faithful to the content of the books on which it is based, and the real Edward Snowden’s comments on social media suggest it is a faithful reflection of his own views and perspective.

More importantly, Snowden’s actions were heroic in their own right. He knowingly and intentionally sacrificed a great deal, both professionally and personally, for the sake of moral principles, especially his fundamental belief in transparent democratic governance. Stone’s film honors that spirit while provoking important questions about the limits of the government, the value of privacy, and the trade-offs embedded in the pursuit of security as a primary policy objective.