How Occupy Wall Street Nearly Scuttles Hell or High Water

Hell or High Water, one of the most talked about films of 2016, is billed as a modern-day western, “heist crime,” or Bonnie and Clyde. A contemporary western is more apt, and its excellent acting, steady pace, tight story and screenplay will likely make it an Oscar contender. The film also makes me yearn for a day when filmmakers learn economics, because they could use that knowledge to take stories to new levels. What is now a well-crafted genre Western could have become a much better film if the screenwriters had eschewed the self-righteousness of the Occupy Wall Street crowd and given everyone humanity and dimension, not just the thieves and police.

Hell or High Water, one of the most talked about films of 2016, is billed as a modern-day western, “heist crime,” or Bonnie and Clyde. A contemporary western is more apt, and its excellent acting, steady pace, tight story and screenplay will likely make it an Oscar contender. The film also makes me yearn for a day when filmmakers learn economics, because they could use that knowledge to take stories to new levels. What is now a well-crafted genre Western could have become a much better film if the screenwriters had eschewed the self-righteousness of the Occupy Wall Street crowd and given everyone humanity and dimension, not just the thieves and police.

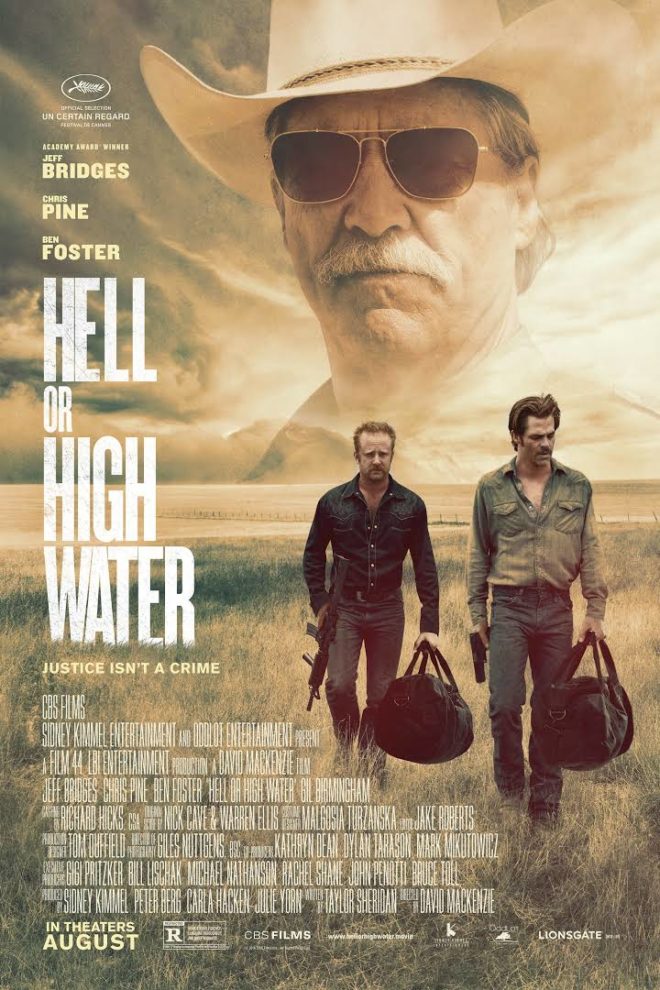

Hell or High Water is low-budget film ($12 million production budget) with high production values, enlisting the acting chops of veteran actors Chris Pine, Ben Foster, Jeff Bridges, and Gil Billingham among others in only a slightly updated cops-and-robbers buddy film. Pine and Foster play brothers—Toby and Tanner—who set off to rob banks to save the family farm from imminent foreclosure by the local bank. Tanner, the rebellious older brother, has just been released from prison for killing their abusive father, and he provides a fitting contrast to the more cerebral and pacifist Toby, who plays the role of the dutiful son.

The two brothers execute a well-planned series of robberies focused on a regional bank’s small town branches, taking the cash from the drawers to avoid larger bills that could be traced. Crusty Texas Ranger Marcus Hamilton (Bridges) is put on the case with his mixed race (Comanche and Mexican) partner, Alberto Parker (Billingham). Hamilton is intentionally offensive, tossing off-color jokes to goad Parker, creating a tension that offsets the brotherly commitment that bonds Toby and Tanner. But it works as the partners come to accept each other’s foibles in their relentless pursuit of the brothers through West Texas.

Tanner, however, is near psychopathic, riding the rush of the heists, his familial loyalty barely keeping him in check. Only Toby’s genuine compassion bridles his older brother, who appears to be a hair’s breadth away from becoming a modern-day version of the murderous Depression Era outlaw Clyde Barrow. This delicate balance between violence and deference to his younger brother’s vision for the robberies—steal just enough to pay off the debt and back child support for his ex-wife and sons—keeps the brothers’ relationship on edge as each robbery ratchets up the stakes with higher levels of violence. In the end, as the Texas Rangers and local law enforcement close in, Tanner and Toby are forced to make choices that can potentially save one brother but not both.

The film works, although a more sophisticated knowledge of markets, bank operations, and housing finance could have significantly elevated the film’s story. The “banker as villain” motif plays on current Occupy Wall Street prejudices, but the bankers in the film are cardboard villains that don’t easily fit today’s world. If bankers were the villains (rather than, say, the Federal Reserve Board) in the recent housing and mortgage crisis, they were the big-city investment bankers, not the rural bankers of small communities like the ones robbed in Hell or High Water. In fact, today’s rural banks couldn’t be more different than the aloof, insensitive, and inconsiderate ones alluded to in the film. Small town banks focus on customer service at the retail level to compete, so they have to pay attention to customer interests. Even larger regional and national banks brand themselves on knowing their clients and customers, a characteristic abundantly clear in John Allison’s first-hand account of BB&T bank described in The Financial Crisis and the Free Market Cure.

Indeed, several scenes in Hell or High Water betray this local familiarity. As the rangers are interviewing a teller at the site of the first bank heist, she identifies the robbers as locals, based on their regional West Texas accents, even though ski masks covered their faces. In the next robbery, the teller (another woman) chats cordially with a local customer about his discovery of old coins that he is now depositing in his account. All the people working for the banks are depicted as nice, everyday people with real connections to each other. The banker-as-aloof-villain doesn’t show up in physical form until the very end of the movie, and instead maintains an invisible presence as motivator and plot driver for Toby.

Clearly, Hell or High Water is attempting to tap into general dissatisfaction with banks in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis that triggered record foreclosures. But retail bankers, particularly those in rural areas, are working within the system and have few options and resources beyond what is in their customer accounts. To extend further loans to failing family farms, which operate in a declining industry, would have jeopardized the solvency of the bank and the hard-earned savings they entrusted in them. The film never alludes to this, even though it’s a point that should be obvious to anyone who has taken a high-school class in economics or personal finance.

Indeed, Toby and Tanner conduct their robberies as is if the cash in the teller drawers appears from a money tree, somehow unconnected to the funds that banks hold in larger accounts. They justify their theft based on the fiction that the money they steal is “the bank’s money,” not their neighbors and friends.

This is unfortunate. Toby’s conflicting attitudes toward the robberies and the violence associated with them could have been heightened if he believed that bank workers were torn between doing their jobs and their personal empathy for the families they serve, particularly when they are struggling. In the real world, these decisions are never easy. (We learn later that oil has been discovered on the property, which means Tanner and Toby’s family would have paid back their loan over time, but this opens up another massive plot hole that won’t be explored here.)

Of course, this complexity doesn’t play into the simplistic conspiracy theory that drives the underlying theme that demonizes business and bankers in particular. On the film’s website, the story hooks directed at audiences include statements such as “Those banks loaned the least they could, so they could swipe your mama’s land,” and “They took everything from your family.” Robbing banks is practical justice, indeed Western Justice, in the romanticized world of the Western Film.

This motif may satisfy the anti-capitalist bloodlust of the screenwriter and filmmakers, but it does a disservice to the viewer by cheapening the plot and diluting the richness of the story. In the end, we have a well-crafted update on the Western genre but a movie that falls short of the sophistication that could have made it a great film and prompted broader discussions.

More on the housing crisis can be found in

- Housing America, edited by Randall G. Holcombe and Ben Powell

- Boom and Bust Banking:The Causes and Cures of the Great Recession, edited by David Beckworth

- Financing Failure by Vern P. McKinley