Why Occupational Licensing Is Unjust, Unneeded, and Increases Income Inequality

Employment gives people earned satisfaction and upward mobility. It can be especially fulfilling when a person is employed in their preferred field. But government policies often deprive some people of these benefits by establishing artificial barriers to employment.

One such barrier is occupational licensure that prohibits employment in a specific occupation unless a would-be worker obtains government permission by first satisfying various licensing requirements. These requirements are typically enacted in the name of “protecting public health and safety,” but their true purpose is to stifle competition from aspiring workers and businesses.

The common perception is that occupational licenses are required primarily of doctors, dentists, nurses, and other high-skill occupations where an unqualified practitioner could do serious harm to a customer. But many government licenses are required of relatively low-skill jobs, and these requirements eliminate the bottom rungs of the economic ladder for many poor and less-educated people.

The Institute for Justice examined licensing requirements for 102 low- and moderate-income occupations such as barber, florist, makeup artist, massage therapist, preschool teacher, shampooer, and tree trimmer in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

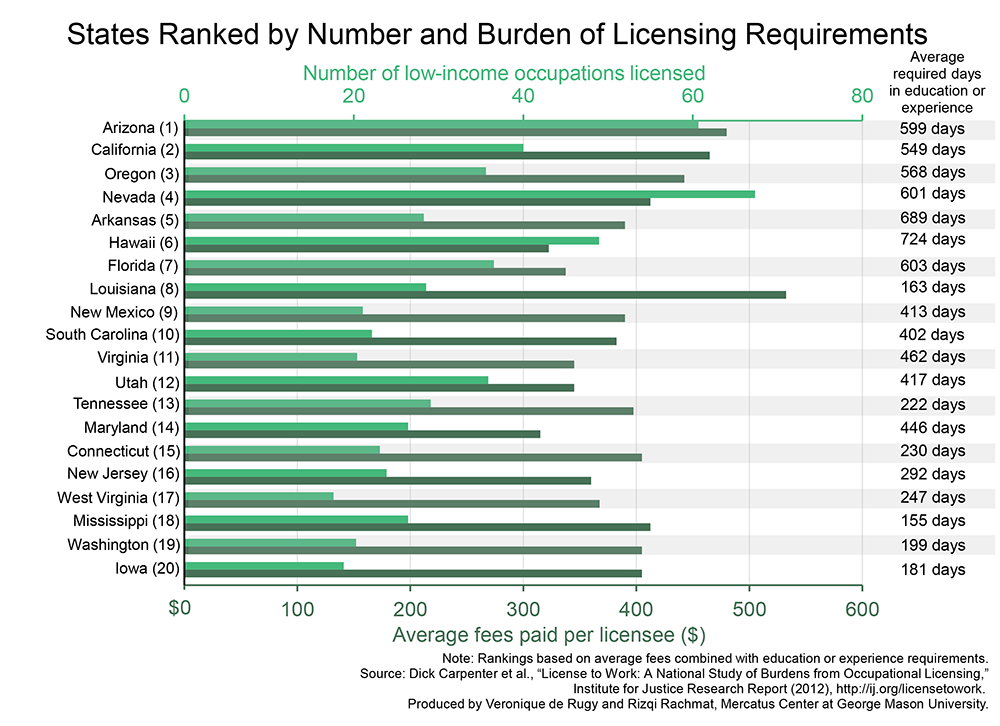

The report found that five of the six states that impose the heaviest licensing burdens in the country are in the West (see the graphic below on the 20 worst states). Consider, for example, the nation’s most populous state of California, ranked second worst.

Graphic produced by Veronique de Rugy and Rizqi Rachmat, Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

California licenses 62 of the 102 occupations studied—the 3rd highest. The average state licenses 43 of the occupations.

California charges its aspiring workers an average fee of $300 in the occupations it licenses, and imposes an average education-and-experience requirement of 549 days. Would-be workers must also pass one exam in the licensed occupations. The average state requires $203 in fees and 307 days in education and experience.

A year and a half of education/training, $300 in license fees, and one passed test might not sound like a heavy burden in California, but to a poorer or less-educated person these can be roadblocks to entry into their preferred field. Time spent in education is typically time spent not earning income, so the opportunity cost of the education requirements alone, in terms of foregone income, can be prohibitively expensive.

The report also found that California:

- Is one of only a few states that license tree trimmers, landscape workers, dietetic technicians, psychiatric aides, still machine setters, funeral attendants, dental assistants, and farm labor contractors.

- Requires tree trimmers and landscape contractors to hold a contractor’s license, requiring four years of training—the most burdensome requirements in the nation for those jobs.

- Imposes four years of education-and-experience requirements with fees and examinations on would-be construction workers. Many states either require no education or experience or do not license this occupation at all.

- Is the only state besides Florida to require farm labor contractors to pass a test.

- Has the longest education-and-training requirement—a full two years—for teachers’ assistants.

California’s heavy licensure burdens make it harder for people to get hired or start new businesses that create jobs. The barriers are especially harmful to poorer people aspiring to climb out of poverty, those with less education, and minorities. People with means and education are little affected by licensure rules, while the poor and minorities can be shut out of entry points into the job market. This is unjust and regressive.

People have strong incentives to obtain the education they need to be qualified for employment in their preferred field. Businesses have strong incentives to screen prospective employees for minimum qualifications and to provide needed on-the-job training for employees. Professional and occupational associations often maintain certification standards. Customers often share bad experiences through word of mouth and social media. They also have strong incentives, encouraged by personal injury lawyers, to sue if they are damaged. These multiple layers provide sufficient protection of “public health and safety.” Government licensure is unneeded.

The real reason for government licensure is to artificially restrict entry into occupations to increase the wages of current practitioners. In the 1950s, one out of 20 U.S. workers were required to obtain a government license. Today that number is nearly one out of every three workers, according to economists Morris Kleiner and Alan Krueger.

Licensure increases the wages of current practitioners by 15 percent by erecting barriers to outside entrants. And these barriers disproportionately exclude the poor from jobs. Occupational licensing requirements, therefore, tend to artificially increase income inequality—a hot topic among progressives these days.

Lawmakers should eliminate occupational licensing requirements, which harm people of modest means the most.