The Dilemma of LNG Exports and U.S. Energy Security

President Trump earlier this month suggested to Premier Ishiba that Japan buy more U.S. fuel and participate in a $44 billion project to develop liquified natural gas (LNG) in Alaska. If pricing is competitive, increasing and diversifying LNG sources would be beneficial for Japan, an important ally. Increasing LNG sales would be positive for U.S. gas producers’ revenue, but it could also increase domestic gas prices, erasing a U.S. competitive advantage, hurting consumers and businesses alike. These two competing factors must be balanced, and U.S. domestic gas production must grow.

The U.S. Gas Market

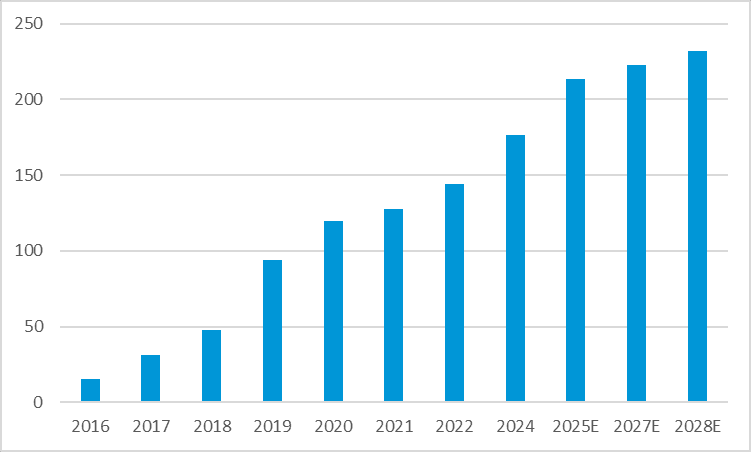

The buildout of U.S. gas liquefaction capacity over the last decade has been stunning, and is to continue, hitting 232 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year by end-2028. Installed capacity may rise even further now that the Department of Energy has resumed issuing LNG export permits after rescinding the Biden-Harris administration’s freeze on new permits and other anti-growth policies.

Figure 1. U.S. LNG Export Capacity Continues to Increase Dramatically

Installed Annual Peak Nameplate Capacity, bcm/year

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

To provide feedstock for rising LNG output, U.S. natural gas production needs to increase. Otherwise, gas will be diverted from other uses. Alternatively, the price of natural gas must rise to balance supply and demand, increasing the cost of a whole range of products from electricity to fertilizers.

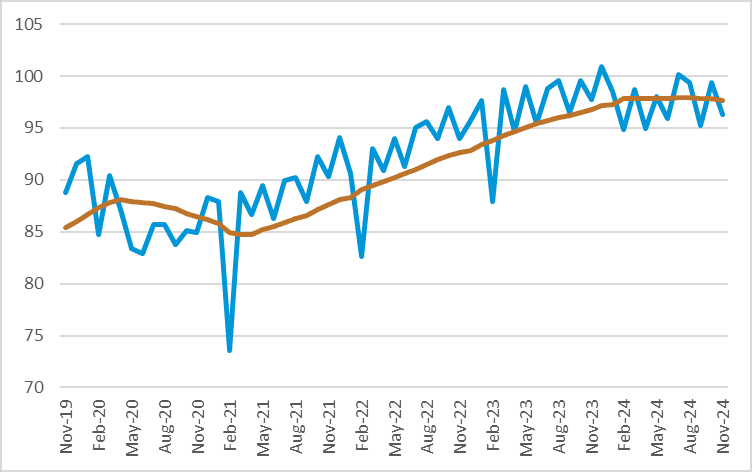

However, domestic production has been flat over the last year as seen in the trailing 12-month average in Figure 2. This was due in part to low natural gas prices, which fell below $2/ MMBtu for the first time since Covid, leading producers to shut in production and decrease rig count. Prices have recently recovered to above $4/MMBtu, in part due to colder weather. It is reasonable to hope that producers will expand output in response.

Figure 2. U.S. Natural Gas Output Has Stagnated Recently

U.S. Natural Gas Marketed Production, Monthly and Trailing 12-Month Average, bcm/month

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

In 2025, the EIA expects a 1.4% y-o-y increase in output followed by a 2.4% increase in 2026. However, consumption is expected to rise 2.9% in 2025 and another 2.8% in 2026. Rising consumption is driven by economic growth: real GDP is forecast to expand by 2.3% in 2025 and 1.8% in 2026. Also, gas-fired capacity is likely to meet much of the rising demand for electricity for data centers and AI, especially since we have a Secretary of Energy who has actually worked in the business and understands that solar and wind cannot reliably provide the amount of energy needed.

If the pace of demand growth exceeds that of supply, natural gas prices are likely to rise. The Trump administration’s policies to “unleash America’s affordable and reliable energy” should stimulate production. However, permitting and construction of energy infrastructure, particularly pipelines, will take time. Also, NIMBY activists are likely to resist progress in areas that lack critical infrastructure, such as gas pipelines in New England, where electricity reliability is at high risk of disruption.

While higher prices will help gas producers, direct and indirect consumers of gas—nearly every American and business—will suffer. The economic damage suffered by the latter is likely to exceed the gains of the former. A better alternative might be to boost output of higher value-added products. Already, domestic ammonia production has increased from 11.6 million tons in 2015 to 15 million tons in 2024. Increasing output of downstream products from complex fertilizers to plastics and textiles could strengthen the U.S. economy and add jobs.

Effect on Global Markets

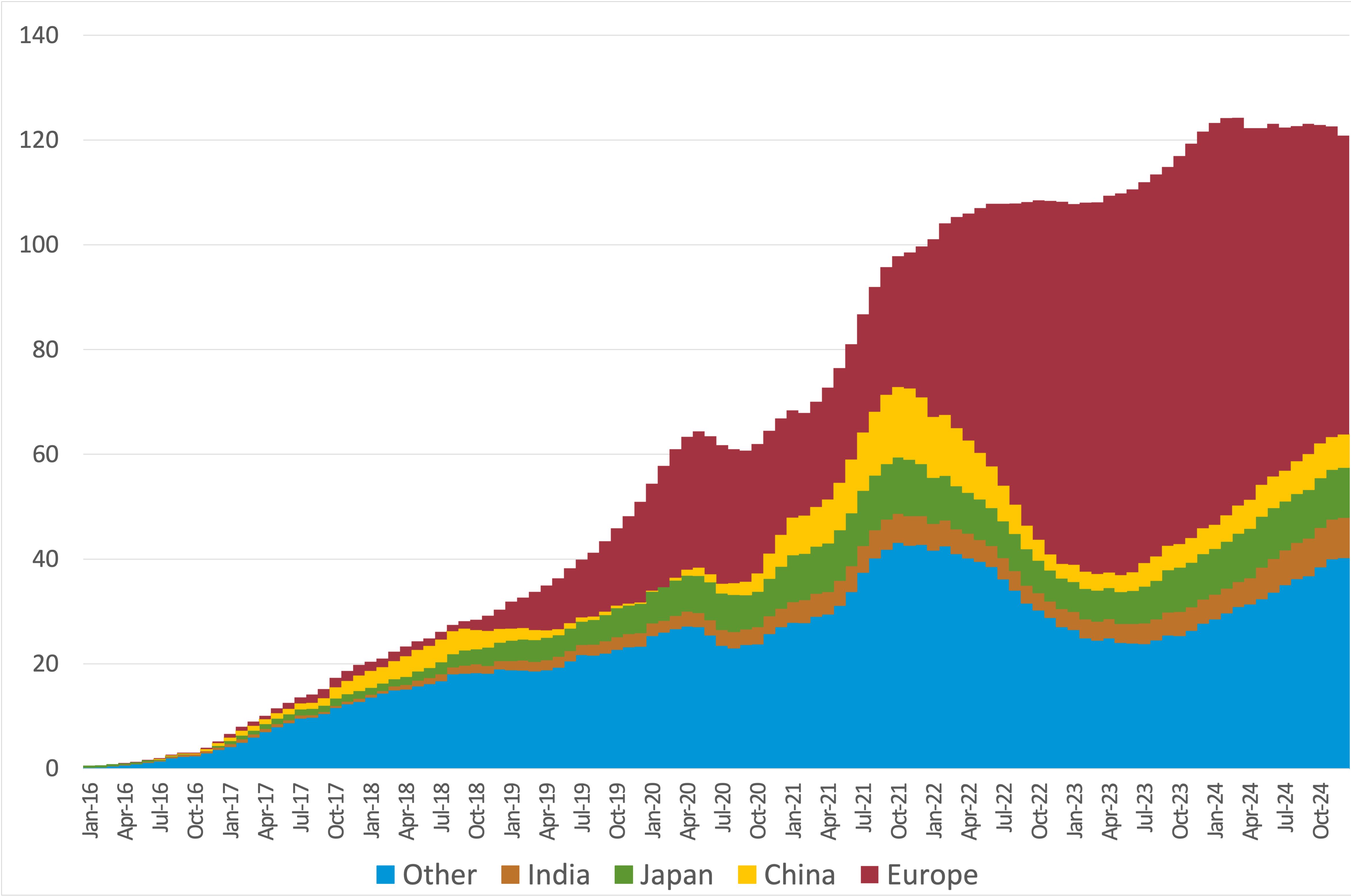

Due to pipeline closures over the last three years and outright sabotage, Europe has lost access to inexpensive Russian gas. To replace this gas, Europe has been importing greater amounts of LNG, especially from the United States. Because this gas is more expensive, the European economy has suffered and many businesses have closed or relocated. In Germany, once Europe’s economic engine, exports declined 0.8% year-on-year in 2024, and the economy contracted by 0.3%, the second year in a row. The prospects for 2025 do not look good.

Figure 3. Europe Has Been Hoovering Up U.S. LNG

U.S. LNG Export by Major Destination, Trailing 12-Month Average, bcm/month

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

In the medium term, the outlook for gas sources for Europe does not look great. In 2024, Norwegian gas exports soared by 6.9% to record levels. However, output is to decline 2.9% in 2025 and continue its downward trend for the next several years. North Africa, a traditional source of gas for the EU, has decreased exports due to rising domestic consumption and infrastructure bottlenecks. Imports from Azerbaijan have been trending down and are also limited by pipeline capacity. Additionally, the European Parliament has called for an end to imports from that country due to its human rights situation and seizure of Armenian land.

In the developing world, Europe attracting additional LNG supplies has priced many countries out of the market. Bangladesh and Pakistan have had to hike prices dramatically and ration electricity, causing riots. Countries of the Global South, as well as China and India, have aggressively built out coal-fired electricity capacity to secure energy supplies; coal is inexpensive and easily sourced. However, burning coal has very negative health effects, locally and globally.

Historically, Asia has been a popular destination for LNG due to higher prices. In 2024, the U.S. accounted for 9.6% of Japanese LNG imports, while Russia’s share dipped to 8.6%. Both are dwarfed by Australia’s 40% share.

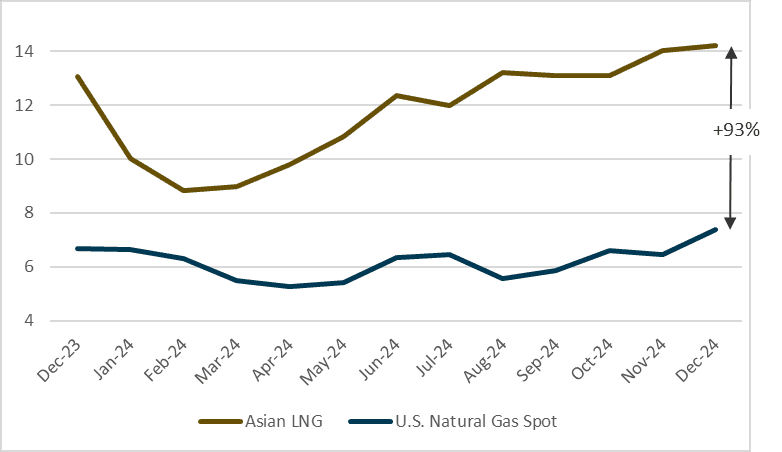

Figure 4. Asian LNG Trades at a Hefty Premium to U.S. Natural Gas

Asian LNG and U.S. Spot Natural Gas, monthly, $/MMBtu

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, St. Louis Fed

But Australian production is to decline going forward, because no new major projects are underway due to lobbying for “green” policies; this indicates potential for others to expand supply. The viability of gas production on Alaska’s North Slope—with transport through an 800-mile pipeline to an LNG export terminal in southern Alaska—will depend on the total cost of the project. Another variable is import of Russian LNG, which should rise if sanctions, particularly on liquefaction technology, are lifted. Indeed, opening markets for U.S. natural gas producers has been a major motivating factor behind these sanctions.

Strategic Approach

In making export decisions, the United States should consider the strategic nature of natural gas: the amount of natural gas in the world is finite, although technology is constantly increasing the amount of reserves, which are economically viable for extraction. In other words, every molecule that the United States has is a molecule that other countries do not have. Therefore, there is a logic to keeping reserves under our feet and consuming foreign countries’ gas, especially since we pay for it with dollars created by the Federal Reserve, unbacked by physical assets.

Understandably, owners and management of gas companies want to produce and sell their gas; otherwise, they do not get paid. If in the future gas were to become obsolete, then it makes sense to extract as much as possible now. However, superior energy sources seem unlikely in the foreseeable future. Fusion has been five years away for five decades. Wind and solar cannot power a modern industrial society.

Furthermore, existing gas-fired plants are very long-lived assets and will require fuel for decades. There are also many non-energy uses of natural gas, such as petrochemicals. Fertilizers from natural gas that are responsible for half the nitrogen in our bodies have no substitute.

Increasing exports of abundant, inexpensive U.S. hydrocarbons is a clear economic win that should be free from government interference. At the same time, unnecessary regulations and restrictions on U.S. gas production must be removed to ensure domestic prices remain low, allowing market forces to drive economic growth. If the U.S. aims to be an industrial and hi-tech powerhouse rather than merely a supplier of raw materials, then an open and competitive energy market is essential to securing the affordable energy needed for prosperity.