To Reduce Homelessness, Donald Trump Must End Housing First

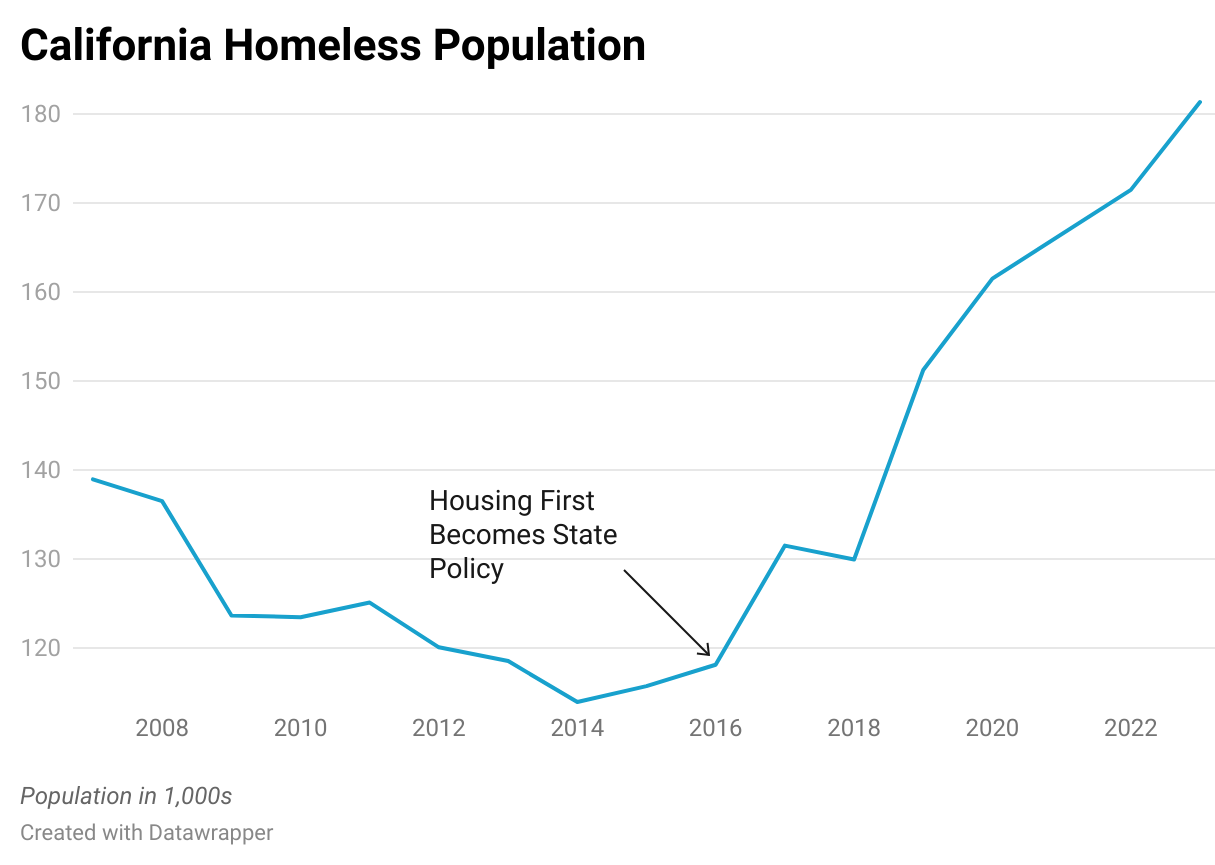

Homelessness in the United States has grown by nearly 19 percent since its low point in 2016. In 2023, the unhoused population reached its highest levels since we began tracking homelessness, but with the new year and new administration come opportunities to reverse this troubling trend. To do so, President-elect Donald Trump must reverse Obama’s Housing First mandate that has guided homelessness policy for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) since 2013.

In a nutshell, Housing First advocates believe that most of the problems associated with homelessness—such as substance abuse and mental illness—are not causes of homelessness, but byproducts of it. Housing First policies, therefore, deemphasize treatment programs and emergency shelters to prioritize placing people immediately in subsidized housing.

During Donald Trump’s first term, he seemed inclined to shift federal policy away from Housing First. He appointed Robert Marbut as head of the Interagency Council on Homelessness. Marbut was the founding president and CEO of San Antonio’s massively successful Haven for Hope, which takes a more holistic approach to addressing homelessness that includes things such as substance-abuse treatment and workforce training to help clients become self-sufficient. Unfortunately, Trump declined to overturn the Housing First mandate, much to the frustration of HUD Secretary Ben Carson.

HUD enforces compliance by withholding federal grants from service providers who do not follow the Housing First playbook. This means that organizations that receive funding from state and local governments or private donors can still pursue alternative strategies, with the exception of California, which has been the only state with a Housing First mandate since 2016.

The failure of Housing First is therefore most apparent in California, where both state and federal funds are reserved for entities that abide by the Housing First guidelines. California’s homeless population was slowly declining before Housing First became state policy, but the Golden State has since added 10,000 new homeless people to its population every year, amounting to a staggering 54% increase since 2016, according to HUD data.

There are many problems with Housing First, but perhaps the most significant is that it treats all homeless individuals as utterly incapable of achieving self-sufficiency. Housing First is anchored in permanent-supportive housing, essentially making beneficiaries lifelong wards of the state. Residents of permanent-supportive housing are no longer classified as homeless, but the subsidies that maintain them still come from homelessness budgets, drawing resources that could be used to help others. This helps explain why both homelessness and homelessness spending have skyrocketed since Housing First became official policy.

Housing First also directs outreach workers to prioritize the most desperate cases—according to “vulnerability assessment tests”—which amounts to neglecting many in need until their condition severely deteriorates. Longtime homelessness advocate Kevin Dahlgren interviewed a woman whose vulnerability assessment score was too low to qualify for housing, even as her hair was falling out due to spider-bite wounds, and another who was denied housing until she tragically lost her legs to frostbite.

Homelessness also correlates with higher rates of substance abuse, but federal grant recipients cannot impose sobriety requirements on housing. With no encouragement for recovery, addiction remains rampant, and the privacy afforded by supportive housing increases the likelihood of overdose deaths. One study found that people placed in supportive housing were 19 times more likely to die from an overdose than those in congregate shelters or even living on the streets. And because sober housing is not permitted under Housing First, people who do not use drugs —including families with children—are placed in the same buildings as addicts and dealers.

Although alternative strategies—such as the Clinton-era treatment-first model—may better ameliorate homelessness, the new administration should resist the temptation to replace one policy mandate with another. When the government ties such mandates to taxpayer funding, they necessarily reward procedure, rather than outcomes. The best reform Trump could make would be to repeal the Housing First mandate and replace it with nothing, giving service providers the freedom to experiment and discover which homelessness strategies are most effective.