Neoliberalism Never Happened

Neoliberalism is a myth. The concept suggests that starting in the 1970s Western economies have been shaped by free-market principles, the state has retreated, and markets have reigned supreme. And yet, the last fifty years were not about liberalizing, but about strengthening the state. Neoliberalism never happened. Instead, what unfolded was neostatism—a strategy where governments restructured their role to protect and expand their power. From the late 1970s onward, policies branded as “neoliberal” were crafted not to relinquish state control but to reassert it. And today, as overt state intervention returns with a vengeance, it becomes clear that the “neoliberal era” was a carefully managed illusion.

The 1970s marked the end of an era. State intervention in Western economies, bogged down by stagflation, soaring unemployment, and social unrest, faced an existential crisis. The Phillips Curve, which posited a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment, was undeniably disproven, along with the broader framework of Keynesian economics. For decades, governments had directly managed economic and social life. But by the mid-1970s, this approach had run aground, eroding trust in state legitimacy.

Faced with collapse, political elites reinvented the role of the state. What emerged was not a retreat but a recalibration. Inflation was reframed as public enemy number one and wage growth was aggressively controlled to shield monetary policies from blame for inflation.

Margaret Thatcher’s privatizations in the UK did not cede control to markets; they concentrated economic power in state-regulated industries. Ronald Reagan’s tax reforms in the US, far from dismantling the state, switched its financial base more resolutely to monetary expansion. In both cases, the state simply shifted its strategy.

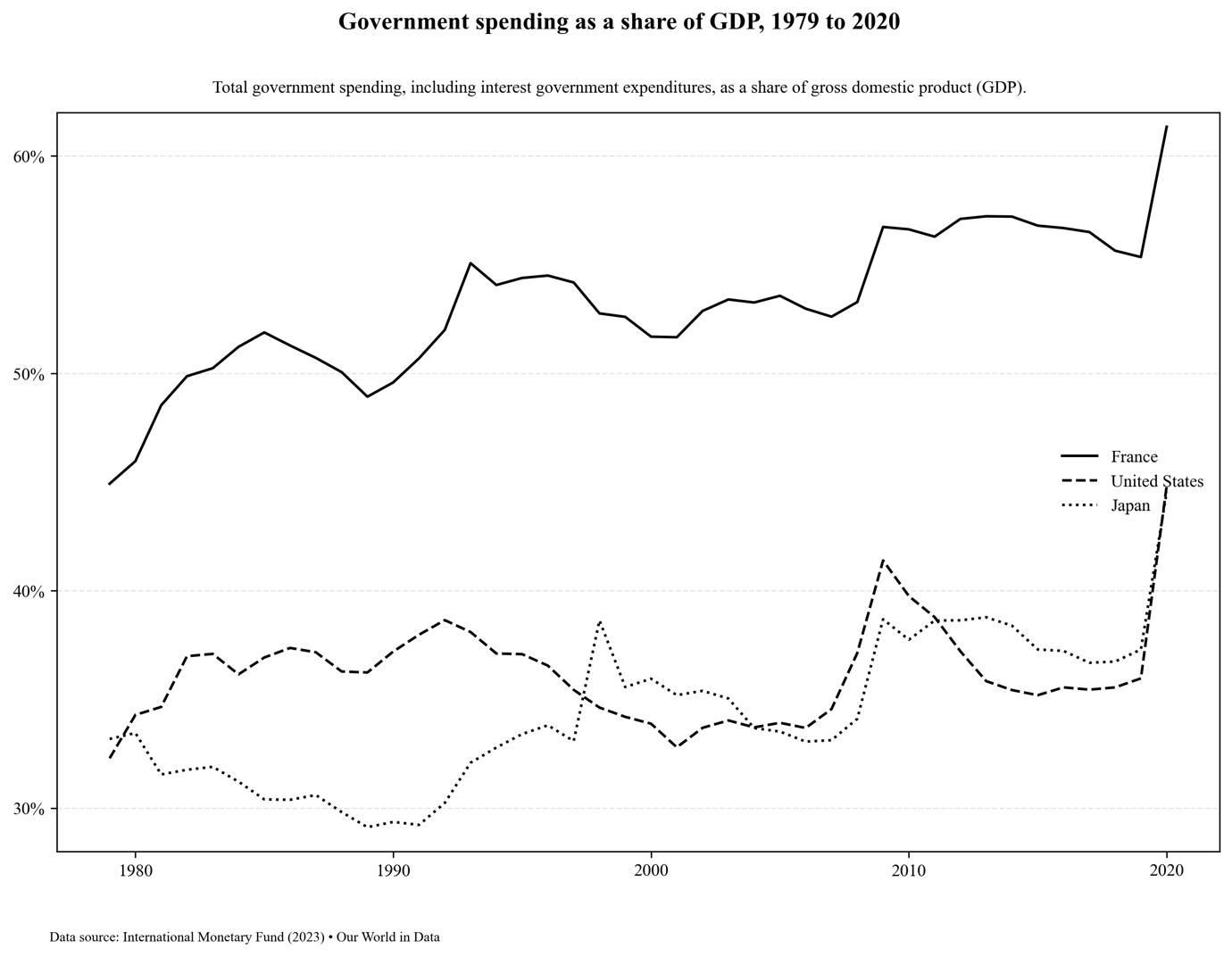

Governments moved from direct management to indirect regulation, all while maintaining the ultimate levers of control. The graph that follows demonstrates that, despite claims of austerity, government spending did not decline over the decades—on the contrary. Far from shrinking, the state merely changed its appearance.

Despite limited privatization in sectors like telecommunications and energy, governments retained control through regulatory bodies. These were not free markets, but hybrid systems designed to protect state interests.

Deregulation, too, was a misnomer. Take the financial sector. Deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s did not unleash the market; it restructured it under state supervision. Central banks gained independence, but this “independence” merely insulated them as tools of state policy. The 2008 financial crisis laid this bare as governments and central banks coordinated massive bailouts.

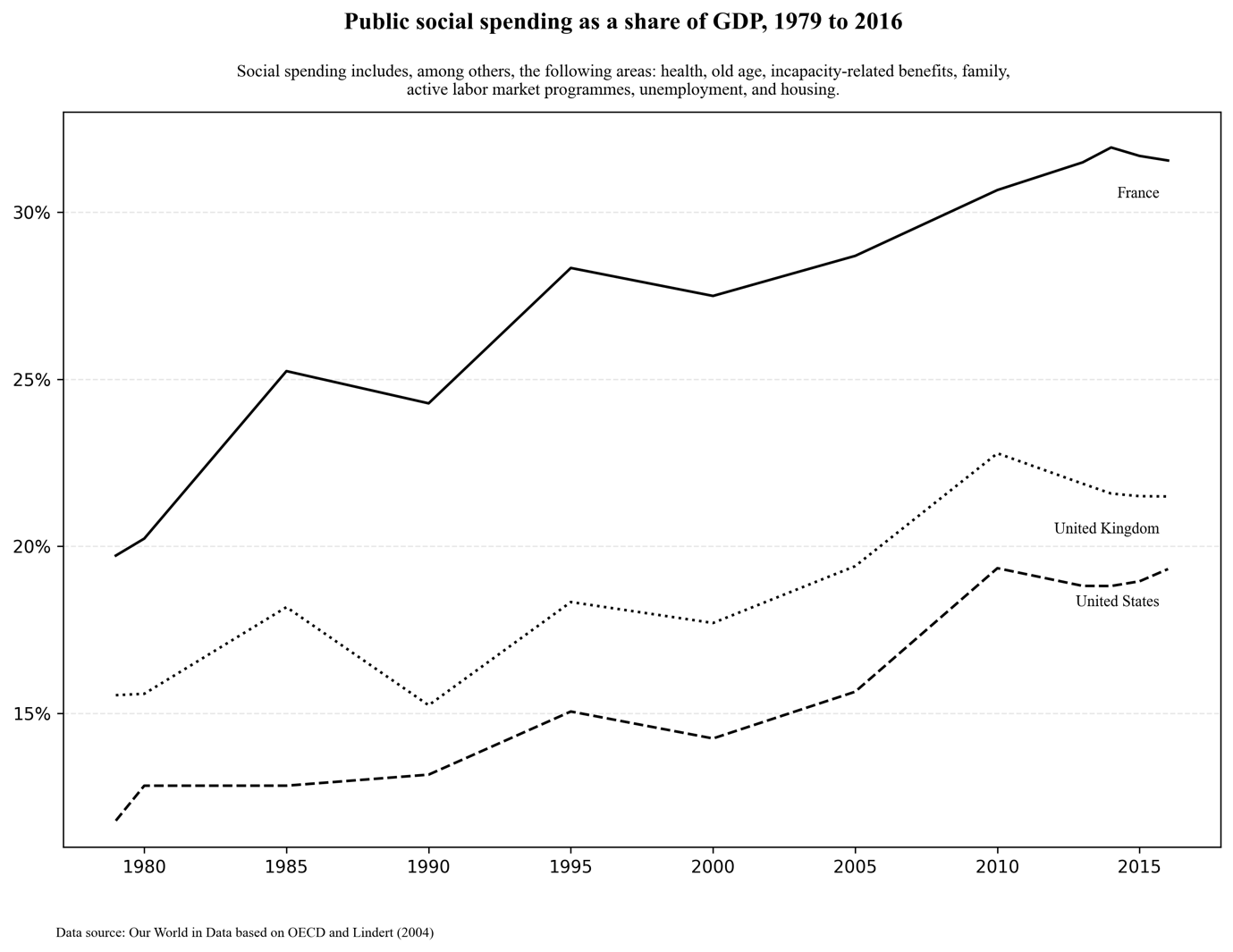

This approach extended beyond economics, reaching into every aspect of public life. The subsequent graph reveals this trend, showing that welfare spending expanded as governments reshaped their programs. Initiatives such as workfare in the United States and active labor market policies in Europe paved the way for new government programs.

Far from a retreat, this was the state consolidating its power. Neostatism thrived under the guise of neoliberalism, with policies serving the strategic needs of the state rather than free-market principles.

By the late 2000s, many declared the death of neoliberalism. The rise of tariffs, state bailouts during economic crises, and resurgent nationalism were seen as signs of markets losing their dominance. But these shifts were not a retreat from neoliberalism; they were its logical evolution. Neostatism was adapting, consolidating the state’s grip.

Take the 2008 financial crisis. Governments around the world intervened massively, rescuing banks supposedly to stabilize markets. Far from exposing the limits of neoliberalism, this revealed its core: markets only existed under the watchful eye of the state. The crisis did not kill neoliberalism—it unmasked its true nature as neostatism.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this trend, with economic lockdowns, massive stimulus packages, and unprecedented public health measures showcasing the state’s ability to control both the economy and society. Regulations mushroomed, from mandates for businesses to surveillance measures on citizens. Far from abandoning its role, the state doubled down, proving that neoliberalism’s alleged decline was nothing more than neostatism’s culmination.

Why, then, does the myth of neoliberalism persist? Part of the answer lies in its rhetorical utility. Framing economic challenges as the result of unfettered markets absolves the state of responsibility. It shifts blame for crises onto “market excesses” while justifying further state intervention.

For example, rising inequality is often attributed to neoliberal policies like tax cuts or deregulation. However, a closer look reveals that inequality flourished under monetary expansion, regulation, and cronyism, which were anything but laissez-faire.

The public and academic discourse around neoliberalism fuels this myth. Terms like “market fundamentalism” obscure the state oversight. The confusion enables the narrative of neoliberalism to thrive and the state’s role to expand.

The truth is simple: the state never let go. Under the guise of market liberalization, it has steadily extended its reach. Today, we see this clearly in the rise of tariffs, censorship, and direct economic interventions that shape markets according to political imperatives.

Neoliberalism is a misnomer. The last fifty years have been defined not by the retreat of the state but by its consolidation. Neostatism has driven policies branded as liberalization, concealing the state’s enduring power and control.

Recognizing the reality of neostatism is not just an academic exercise—only by shedding the myth of neoliberalism can we confront the real challenges of state overreach.

The greatest irony of our time is this: at the peak of state power over the economy and society, most still believe they live in an era of unfettered neoliberalism.