The Hidden Politics Behind the Nippon-US Steel Deal

According to reporting by Reuters, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS) has blocked the $14.9 billion takeover of US Steel (USS) by Nippon Steel (Nippon) due to the “consequences to national security” and a “continued loss of viable commercial production capabilities.” Because the United States defends Japan’s sovereignty, it is difficult to imagine the latter undermining US national security. Moreover, Nippon has agreed to no “layoffs or plant closures or idling of US Steel facilities.” Domestic politics may motivate this decision, namely helping Democrats in contested races, particularly Vice President Harris.

If the buyer were Chinese, preventing the deal on national security grounds might have more merit since the two countries are rivals engaged in various disputes. However, since its defeat in WWII, Japan has been a US vassal, with only a small self-defense force, in part due to constitutional renunciation of war. Under pressure from US hawks, Japan has approved a record military budget of $56.7 billion. Still, without US protection, Japan could not defend itself against China. Therefore, undermining US security would be tantamount to committing hari-kari.

In the past, Japan has been allowed to buy assets with far greater strategic significance. For example, Toshiba purchased Westinghouse Electric, a leading provider of nuclear fuel and services to utilities globally, in 2006, when the nuclear power market was taking off. In that deal, CFIUS granted regulatory approval less than four months after the sale agreement was signed.

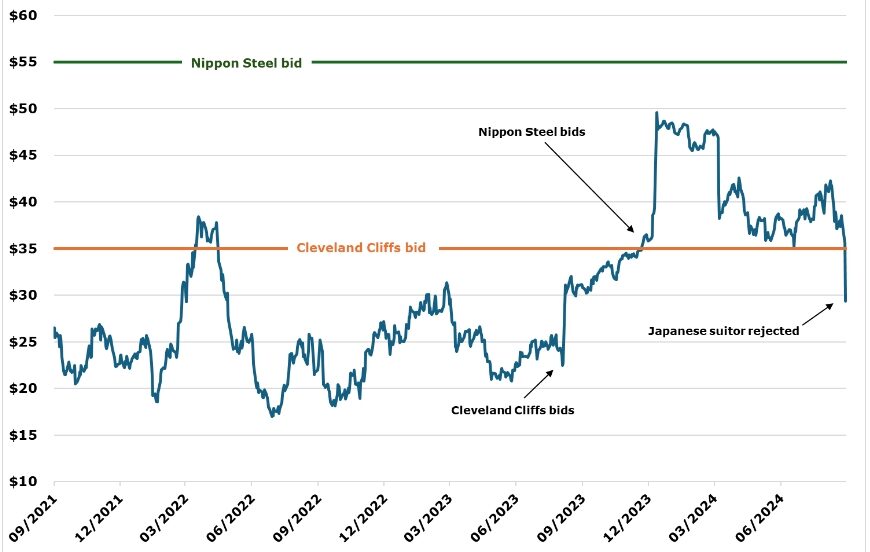

Competition is another possible issue. Last year, steelmaker Cleveland Cliffs offered $8.3 billion for USS. The union supported that bid, but the company rejected it. Automakers wrote to Congress, complaining that the combined company would control 65-90% of automotive steel. This is not the case with the Nippon bid.

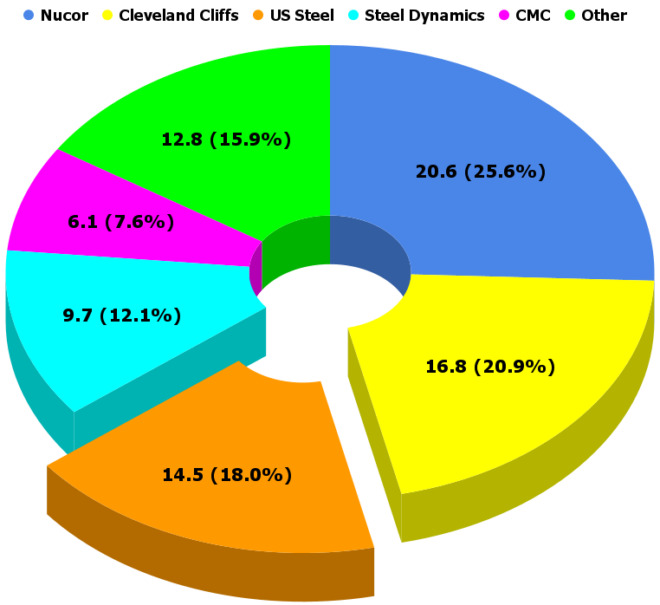

USS is a large player in the domestic market, but it does not have a monopoly or even a 50% market share, which could lead to FTC and legal action. However, enforcing antitrust laws appears selective and influenced by politics, as seen in Google’s 88% US market share. This selective enforcement could also be used to prevent the acquisition of USS.

Figure 1: US Steel Is Number #3 Domestically

2022 US Steel production, million metric tons and (market share %)

Source: World Steel Association, CMC SEC Fillings

Lost in this discussion is the reason for the deal: to help arrest USS’s decline and stave off possible plant closings and bankruptcy. Steel prices have steadily declined since COVID-19 closures and supply chain disruptions. Given the cooling Chinese economy, particularly the construction sector, this trend looks set to continue.

The combined company would have a total annual capacity of 88 million tons, the second most in the world, although still dwarfed by China as a whole (over 1 billion tons). As such, the company should benefit from economies of scale. Furthermore, Nippon has promised to share technology and invest billions in existing facilities. Given these factors and the 40% premium to market price the day the deal was announced, USS shareholders approved the merger with 99% of shares voted.

Figure 2: US Steel Stock Trading Has Been a Bit Volatile

US Steel common shares, closing price

Source: NASDAQ

For Nippon, the United States, which has 94.5 million tons of apparent steel use even in post-COVID 2022, represents a lucrative market. The current “green” drive to electrify everything may generate more demand for steel as wealth transfers from taxpayers to favored industries result in the proliferation of EVs and wind turbines.

The next administration may end massive subsidies for these inefficient products that are not demanded by the market. Funds could be directed to more productive uses, such as much-needed infrastructure, which has a significant, long-term multiplier effect on the US economy. This, too, would boost steel demand.

Thus, if the acquisition makes economic sense, has been approved by shareholders and management, and poses no competitive or national security risk, why would the Bidden/Harris White House block it?

The answer may lie in partisan politics.

Pennsylvania, home to USS headquarters and facilities, is a critical battleground state. In Ohio, where USS has a significant footprint, incumbent Democratic Senator Brown is in a tight battle, perhaps prompting him to pen a letter to Treasury Secretary Yellen and others about the “the clear and present threats that a Nippon Steel acquisition poses.”

The unions are opposed to the deal, fearing that Nippon will fire employees and adversely impact workers’ pensions, although the Japanese have explicitly promised not to, and there exist legal and other remedies to address such issues. Blocking the acquisition could garner votes from the union members for Vice President Harris. Traditionally, the Democrats were the party of the working class, but this has changed over the past few decades.

Keeping such a core industry in American hands is also very patriotic. For this reason, most Republicans also favor blocking the deal. President Trump calls for high tariffs to protect US companies and limit foreign ownership.

However, blocking the deal can backfire: If the deal falls apart, USS could be forced to close steel mills and fire workers. (Predictably, this is precisely what USS management threatened after rumors of political roadblocks to the deal surfaced. Just as predictably, Cleveland Cliffs offered to buy those facilities, maybe at the much lower price it offered.) This would devastate the local economy and could sour voters on politicians who lobbied for it.

Worse still is its potential to dent the United States’ standing in the world. We rose to economic prominence via competitive domestic markets and, more recently, through globalism. We have been the champion of free markets and the enemy of protectionism. It would be very hypocritical to announce one set of rules for us and another for everyone else, particularly if this deal sets a precedent.

We’ve seen this movie before. In the 1980s, there was widespread fear that Japan would buy America and that Japanese managers would boss US workers around. After the 1985 Plaza Accord, the dollar’s value against the yen fell sharply. The Japanese went on an aggressive buying spree, snapping up steel mills, movie studios, and real estate, including New York’s iconic Rockefeller Center. At the end of the decade, the Bank of Japan raised rates, sending its economy into a tailspin and popping the asset bubbles.

Then, as now, fears of foreign domination were unfounded. Although imperfect, open markets are still the best path to national prosperity.