Sowing the Seeds of a Crisis With Fertilizer Tariffs

The EU is poised to shoot itself in the foot yet again. To punish Russian misdeeds and reward domestic producers, import tariffs on Russian fertilizer are to be increased dramatically. Cost-benefit analysis reveals that the pain will be limited because fertilizer export revenue is a minuscule share of Russian GDP. However, rising fertilizer prices in Europe will drive food prices up, fueling societal unrest. Rather than using subsidies and tariffs to worsen market distortions, hurting all stakeholders, EU policymakers should tackle the root cause of the problem, namely the lack of inexpensive Russian gas, in turn caused by poor political decisions.

Nitrogen is one of three fertilizers required for plant growth. Half the humans on the planet are here thanks to the Haber process, which synthesizes ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen and natural gas, which is the major input cost. Accordingly, following the sabotage of three Nord Stream pipes and decisions by Poland, Ukraine and Germany to not utilize other pipelines, the price of natural gas spiked, leading prices of ammonia and more complex fertilizers made from it to also jump.

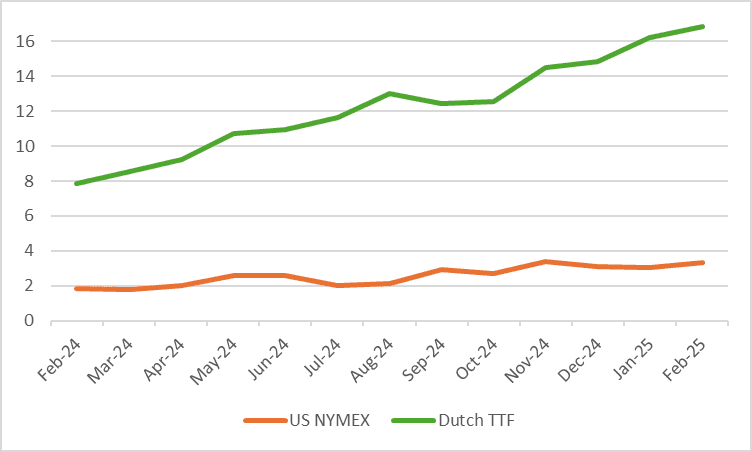

Figure 1: European Gas Prices are Higher than U.S. and Rising

Natural Gas Price, $/MMBtu

Source: MarketWatch

While European prices are nowhere near the levels they reached after the Russian invasion, they are almost four times more than in the United States, a huge competitive disadvantage, and have been rising the last year. Some of the inexpensive Russian pipeline gas has been replaced by more expensive U.S. Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), exacerbating the problem. Other input costs, such as electricity, have also risen.

Not content with the current level of market intervention, the European Commission in January proposed increasing tariffs on Russian nitrogenous fertilizers from the current 6.5% to €40-45/ton (roughly 14% at current prices) effective July 1, 2025, and eventually rising over the next three years to the eye watering level of €315-430/ton. Depending on the product, this tariff could equal 100% of the value.

On its face, the stated goal of punishing Russia makes little sense: Because last year Russian exported to the EU €2.1 billion of fertilizers, a mere 0.03% of GDP, the fallout for the economy as a whole will be basically nil.

More importantly, higher fertilizer prices are higher input costs for farmers. Farmers will not, and often cannot, absorb these added costs, which therefore will be passed onto consumers in the form of higher food prices. Alternatively, farmers could use less fertilizer, keeping total costs down. However, this will lower crop yields. Since demand for most foodstuffs is inelastic, reduced supply results in higher prices—the same result.

EU “green” policies add more costs for farmers. To fight a hypothetical climate crisis, European Commission bureaucrats are implementing the Green Deal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030, an unrealistic goal that can only be attempted by shuttering more European industry. Furthermore, any such reduction would be dwarfed by emission increases in China and India.

Specific policies are designed to decrease the size of farms and herds, without regard to food availability. Other policies are aimed at reducing fertilizer use, promoting organic farming and increasing land left fallow. While noble sounding, these policies result in lower crop yields and, thus, higher prices for consumers.

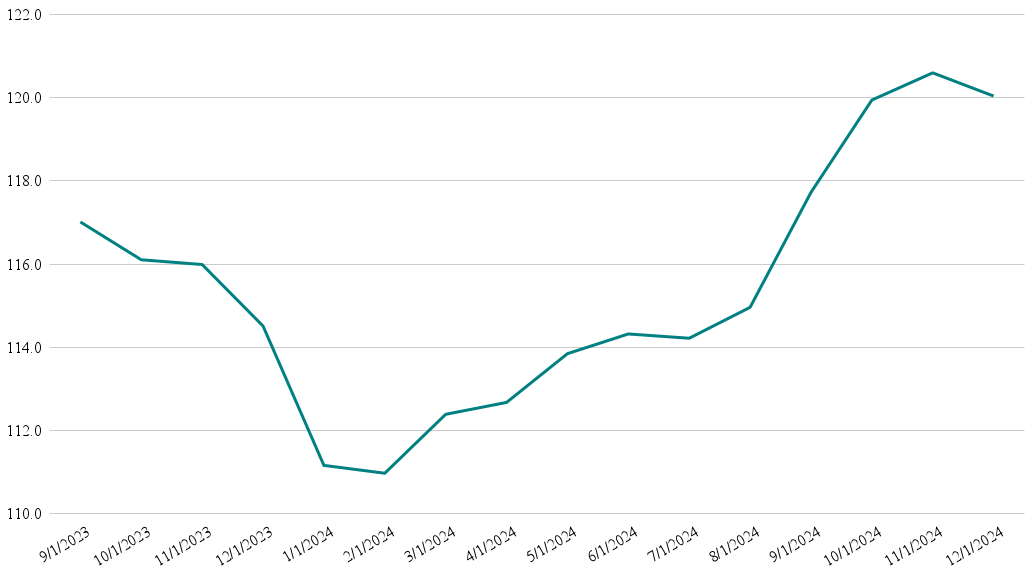

These decisions have already led food prices to rise, although not near the 2022 peak. Public discontent is growing and will rise further as consumers are forced to eat less and substitute less satisfying food. This could lead to riots, especially against the backdrop of economic difficulties and higher inflation, i.e., less disposable consumer income.

Figure 2: Food Prices Are on the Move Again

FAO Real Food Price Index, 100 = Average 2014-2016

Source: UN Food and Agricultural Organization

These policies have been aptly termed a “war on farmers.” Regulatory overkill as well as higher prices for fertilizer and fuel, particularly diesel, have ignited protests across the EU. Thus, government interference in the market, namely political decisions to remove Russian energy from the market, both directly as fuels, and indirectly as inputs such as fertilizer, have the potential to destabilize European society.

These policy choices have fueled the popularity of nationalist parties, such as AfD in Germany and FPÖ in Austria. European governments have been expending maximum effort to keep them from power, and legacy media labels them “far right,” the catch-all term for the “bad guys.” In reality, their rise in popularity—FPÖ is currently polling at 35% and AfD at 22%—is simply a natural reaction to unpopular political decisions made in Brussels and national capitals.

Rather than address the underlying issues, European politicians are attempting to squelch discussion through rules such as the Digital Services Act, which calls for “mitigation measures” against alleged “disinformation.” Such thinly veiled censorship is likely to backfire, increasing the popularity of parties like AfD and FPÖ.

How to bring food prices under control? Increasing imports of cheaper fertilizers would help but hurt European producers’ profitability. Tariffs on Russian fertilizer will guard European producers’ bottom line but at the expense of consumers.

Another solution would be to increase imports of less expensive food but this hurts EU farmers. For example, Ukrainian grains are cheaper because their farmers have no limits on fertilizer, use pesticides banned in the EU, and, in general, face a lower regulatory burden. However, in Spring 2023, a flood of imports hurt domestic farmers in several EU countries, leading to bans on Ukrainian products. Recently, the bans were lifted, conditional on Ukraine adopting voluntary export restrictions. Whether imports into the EU can be increased enough to ease prices but not so much as to anger farmers remains to be seen.

A better solution is solving the issue that created the problem in the first place—the corking of inexpensive Russian gas. Lowering this input cost will ease the pressure on EU fertilizer producers, the cost of whose products will decline, to the delight of farmers. In turn, the price of food that they produce will decline and soothe societal tensions.

Germany could certify the one Nord Stream pipe that was not sabotaged and commence annual imports of some 28 billion cubic meters (bcm). Poland could reverse its May 2023 decision to terminate flows through the Yamal pipeline that in 2021 totaled 32 bcm. Ukraine could agree to resume transit of gas that totaled 99 bcm in 2021, perhaps with title to the gas changing hands at the border for better optics. Additionally, sanctions could be eased on Russian LNG projects and associated infrastructure.

Politicians should avoid decisions that make the problem worse, such as increasing sanctions on LNG or dismantling existing pipelines. The latter is particularly pernicious because it is tantamount to eating your seed corn—nothing will grow in the future when the current difficult situation improves. The motivations and goals of those who suggest such things should be examined closely.

It is high time to work toward peace, not fanning the flames of war, which benefits no one. Increasing tariffs and subsidies, to say nothing of sanctions, are undue government interference in the marketplace, and lead to poor outcomes. EU governments should think first and foremost about their people, whom, in theory, politicians are chosen to serve, not just politically connected special interest groups.

With the United States increasingly withdrawing from Europe and Russia getting closer to achieving its goals in Ukraine, European states should start thinking about their relationship with their more powerful neighbor. Given a lower likelihood of U.S. involvement in Europe due to a decline in relative power, the EU should work toward improving relations. Increasing trade barriers is a step in the wrong direction.