Of Budgets and Biases

Austrian economist Gene Callahan likes to remind us that fantasy is not an adult policy option.

We are often reminded of his words in national debates and handwringing over potential budget cuts, whether by the Republican-led Congress, or President Trump’s new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE)—or attempts to address the $36 trillion debt elephant in the room.

Economist Bryan Caplan has pointed out a number of systematically biased beliefs American voters hold about the economy. Generally, Americans tend to hold four basic biases about the economy: an anti-market bias, leading to favor government intervention; an anti-foreign bias, which leads them to underestimate the contributions of foreigners and the benefits of trade; a make-work bias, which equates prosperity with the number of jobs (regardless of productivity or value added); and a pessimism bias, which leads them to think that economic conditions are far worse than they really are.

Biases and ignorance do not just matter for economic curiosity. Indeed, less-informed voters favor systematically different policies than otherwise identical more-informed voters, and those policies tend to involve an increase in government spending.

In this inauguration month, many are belly-aching that DOGE will cut Social Security or Medicare (even if President Trump has explicitly said he won’t, and Elon Musk has specifically said that entitlements are beyond the DOGE purview). Surveys consistently show that the public thinks the federal government spends about 25% of the federal budget on foreign aid (it’s less than 1%). Other surveys show that the median U.S. respondent grossly underestimates U.S. debt; when presented with facts about the debt’s real magnitude, respondents increasingly favor cutting federal spending. The public prefers “tax expenditures” (credits) over “direct outlays” (a check or cash), even if the magnitude and economic result are identical. About 61% of Americans favor raising taxes on high-income households, and it has now become a cliché of class warfare and political soundbites that “the rich” need to pay “their fair share.” Then again, few respondents know two important facts. First, half of Americans don’t pay any federal income tax. Second, of those who do pay federal income taxes, 50% of taxpayers contribute a whopping 98% of tax revenue, and the top 10% of taxpayers pay 75% of tax revenue. What a “fair share” really constitutes will surely change based on perception versus facts.

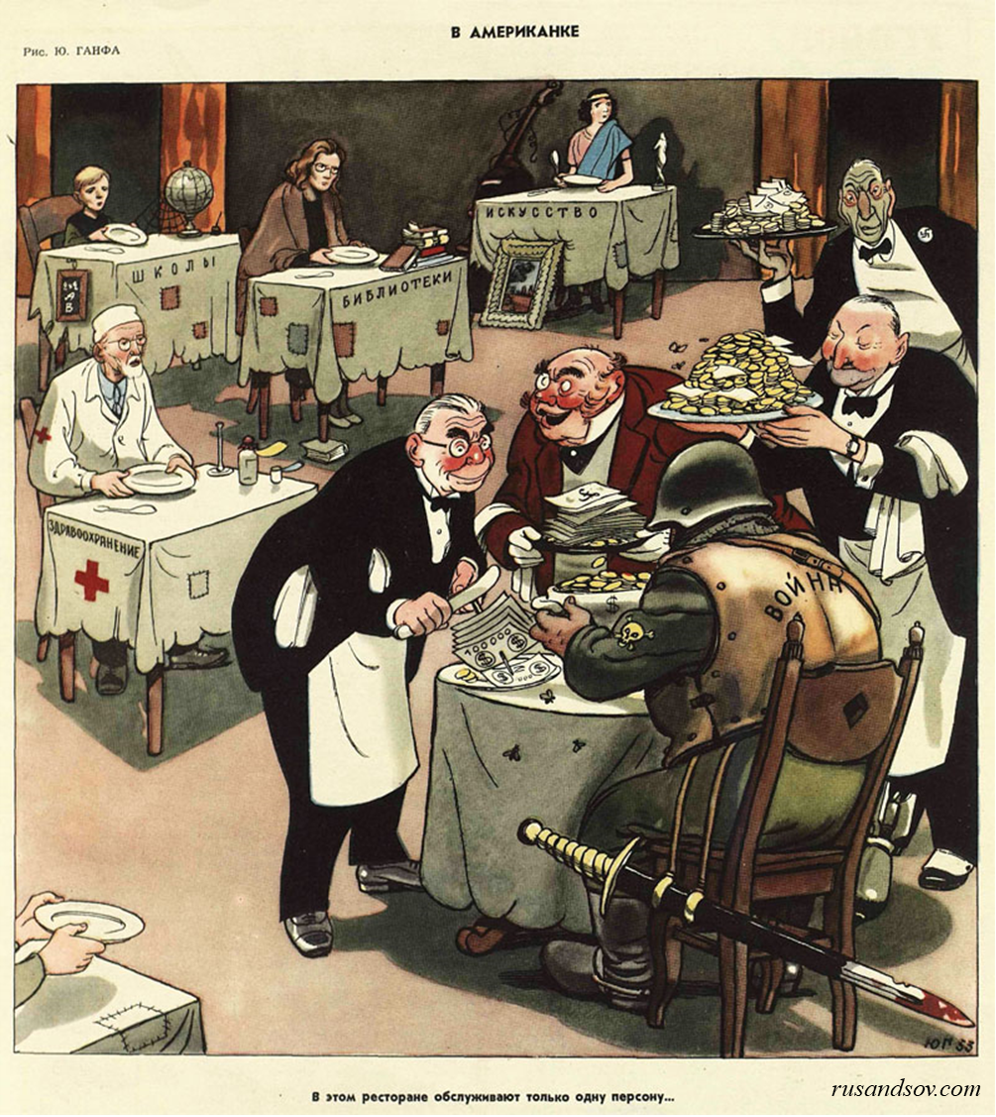

A 1953 Soviet propaganda cartoon has recently been circulating on social media. It complains that nothing has changed, as defense (actually 13% of the total budget) is the only recipient of federal largesse, to the neglect of social expenditures (almost 60% of the total budget).

Given these wildly mistaken beliefs, it’s no surprise that Americans—setting aside ideology—are so divided on what government spending should be. Half of surveyed Americans think the federal government should be bigger, and the other half think it should be smaller. Half think the feds are doing too much, and half think they are doing too little to solve national problems. 43% favor increasing aid to the poor, while 26% think the federal government should provide less; 30% are satisfied with the current level (or, at least, the perceived level).

Before we get into practical (or constitutional) debates about budget cuts, it is a useful exercise to pause for a moment and examine real—rather than fantasy—budget spending. Only then can we have an adult conversation about budget cuts, balancing budgets, and addressing the national debt.

First, the total federal budget ($6.2 trillion or 23% of GDP) can be broken down into two categories: mandatory and discretionary (note that I am using numbers for FY23; FY24 ended on September 30, 2024, and the final numbers are still trickling in; while there was a 7% overall increase in spending from FY23 to FY24, the percentages remain similar). Congress has no annual authority over mandatory spending, which is authorized by prior legislation, unless and until Congress repeals past laws. Discretionary spending, on the other hand, must be reauthorized every year by congressional budget action. Mandatory spending constitutes about 70% of the federal budget and consists primarily of welfare entitlements and interest on the federal debt. Discretionary spending constitutes the other 30% of the federal budget and covers defense, as well as the various operations of the federal government, from education and transportation to justice and foreign affairs.

Reality must be the starting point for serious budget discussions. From there, a budget discussion could take several directions. We could advocate the simple path of trimming waste, without attacking the core. We could address runaway entitlements, which constitute the bulk of the budget. We could have a serious adult conversation about what really constitutes market failure, and where the federal government really needs to step in—rather than buying votes legally through redistribution. We could even (gasp!) boldly return to Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution (as bolstered by the 10th amendment) and figure out how much current federal spending is actually authorized.

My purpose here is not to dig deeply into the details of budget cuts. Both economic theory and political reality will be important parameters. But the first step is to stop making outrageous and uneducated claims, and start instead with reality. Only then can we have a serious, adult conversation about budget reform.