Energy and Economic Progress: Why Hydrocarbons Still Matter

We evolved with the Earth to our current advanced technological state thanks to our ability to find and utilize new sources of energy for productive work. A million years ago, proto humans began burning wood for warmth, cooking, and safety. Homo Sapiens adopted and improved consumption of that hydrocarbon before advancing to coal, which drove machines to replace manual labor, to oil and gas, whose superior energy density allowed planes, ships, and trucks to move people and cargo quickly around the world.

So-called “renewables” should be limited to niche applications where their advantages outweigh their lower efficiency and energy production. Human history has demonstrated that the way forward is better and more sources of energy, not worse and less. The lack of market demand for those sources echoes that basic truth. Continued government interference to force these energy sources on the market will retard the development of society and leave billions in poverty.

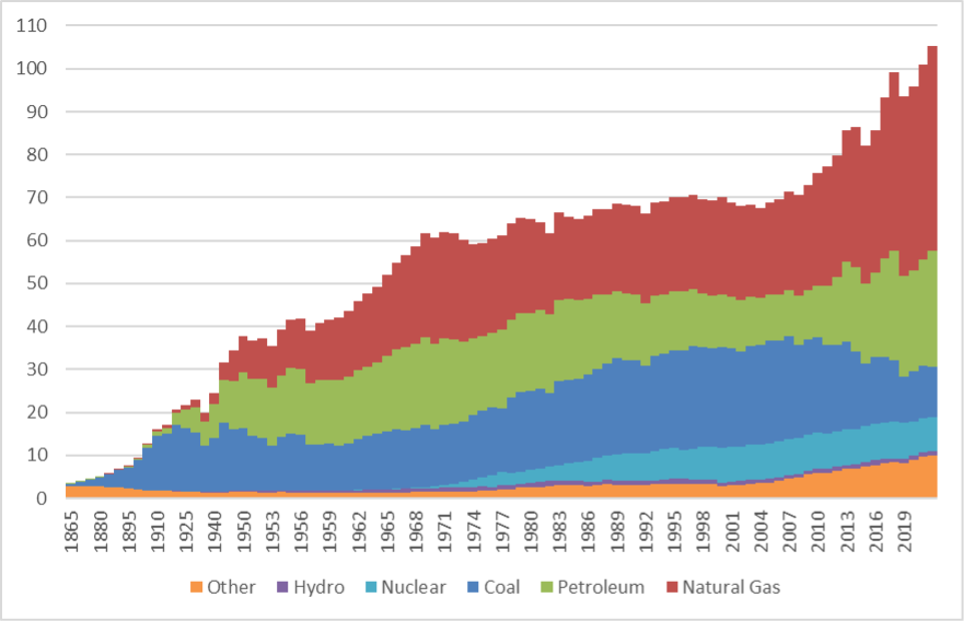

The Industrial Revolution came later to the United States than to Europe. It was slower to spread, reaching scale only after the Civil War. By the late nineteenth century, coal had surpassed wood as a fuel and would remain so until the discovery and development of large oil and later gas deposits prior to the World Wars

(In Figure 1, the “other” category represents wood until the introduction of wind and solar some 40 years ago. Also present are biomass fuels, the classification of which as “green” is dubious because they must be burned just the same as other hydrocarbons, e.g., oil and gas, and thus release CO2.)

Figure 1: Hydrocarbons Dominate the Energy Balance

US Primary Energy Consumption, Quadrillion Btu

Source: US Energy Information Association

Thus, the market and consumers have clearly chosen oil and gas as the preferred fuel to power modern society. Why then do renewables, particularly wind and solar, exist beyond extremely useful niche applications, such as powering remote islands or satellites in space?

The only reason renewables seem even remotely competitive is because of the massive wealth transfers from taxpayers to these politically favored industries. Renewables have been subsidized for decades, but the Orwellian named Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law by President Biden when the nation was still distracted by draconian, unconstitutional COVID measures, was a fiscal irresponsibility gem, estimated to cost $1.2 trillion through 2032. The actual cost will likely be higher as government programs are wont to do. Additional government giveaways are provided at the state level.

Worse still, utilities must pass along higher costs due to renewables’ intermittency and other negative externalities. This helps stoke inflation, which is already elevated due to massive government spending.

Better alternatives include cutting subsidies, providing relief to taxpayers, or directing these funds to useful R&D, such as advanced nuclear and energy storage.

Some argue that forcing renewable energy sources is necessary to undo global warming caused by humans. Even if global warming is real and caused by humans, rather than subtle changes in the Earth’s orbit, it does not follow that a catastrophe is imminent. We have lived through many cycles of global warming and cooling. We have spread to scorching deserts and frozen tundra; we live on high mountains and tropical beaches. The ability to change and adapt is a powerful competitive advantage for our species.

Furthermore, the formulation presupposes a false dichotomy—that nature and man are two separate things. In reality, everything that man does is natural. Dumping toxic waste in a river would be completely natural. (It would also be very stupid.) To analyze man or nature in isolation is to misunderstand the interdependence of systems on Earth.

Regardless, difficulties inherent in climate forecasts, particularly reliance on models that for 40 years have consistently overpredicted temperature increases, are beyond the scope of this paper. The ecological and inflationary impact of the massive amounts of mined materials used in wind turbines and polysilicon wafers is best addressed elsewhere. This is significant considering that the usable life of solar and wind is 15-20 years (assuming no hail or hurricane-force wind) compared to thermal plants that can last over 50 years (the US still operates thermal plants that came online in the 1930s.)

A legitimate concern is the health effects of burning hydrocarbons, particularly coal, which releases particulate matter that can cause lung cancer, asthma and heart disease. But this, too, argues for natural gas, which emits just 0.3% of the particulates that coal does, and nuclear power, whose marginal emissions are nil.

It is positive that no major US coal plans have commenced operation in over two decades but the global significance of this is low. Because they cannot afford or source superior oil and gas, China, India and the Global South continue to massively expand coal-fired capacity to meet their increasing appetite and improve their people’s standard of living. Indeed, the sheer scale of their increases dwarfs any theoretical decrease by the West: In 2023, China brought 47.4 GW of coal-fired capacity online to 1,147 GW or 53% of the world total, compared to just 196 GW in the United States. To fuel this generation, China burned 5.2 billion tons, 60% of total global coal consumption in 2023.

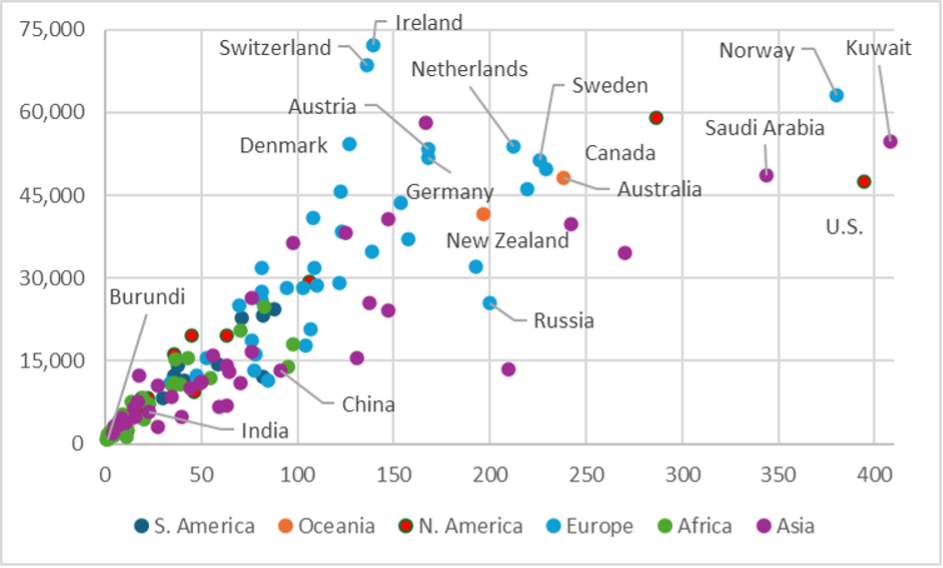

Well-being is intimately linked to energy consumption. Before the coal-fired Industrial Revolution made basic necessities more available and affordable, most people produced barely enough to survive. Poor countries will increase energy consumption by using any fuel necessary to improve people’s quality of life.

Figure 2 illustrates that relationship. The poor countries on the lower left strive to move to the upper right to join the rich who consume more energy and live better. Even dirty coal is desirable, particularly at very low consumption levels, where small increases can have dramatic effects. Expecting poor countries to forgo coal use to improve well-being in favor of wind and solar, which will not meet their needs and they cannot afford, is hypocritical and anti-human.

Figure 2: Economic Well-Being is Tied to Energy Consumption

GDP, $, vs. Energy Consumption, GJ, Per Capita, 2016

Source: Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability

While “that government is best which governs least” is certainly true, clearly some government regulation is needed to prevent profit-maximizing companies from engaging in activities detrimental to society, e.g., dumping toxic waste rather than paying to treat it. But aside from such extreme cases, the market is the best arbiter of what should be. The government picking winners and losers in the energy market is not in the best interest of our society, nation and species.