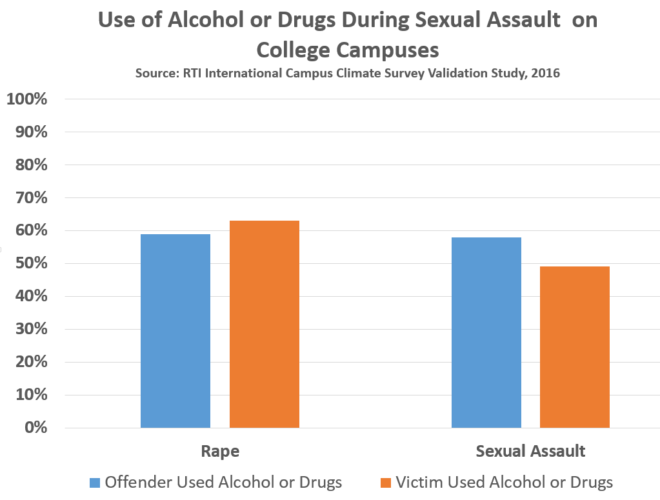

Alcohol Bans Won’t Put Dent in Campus Sexual Assault

Chart created by the author from “Campus Climate Survey Validation Study,” RTI International, Figure 21

Students at Stanford University will be greeted with a ban on hard liquor this fall, all in an effort to control irresponsible behavior among its students and, in part, to address campus sexual assault. Alcohol bans are unlikely to have much of an effect on campus sexual assault and, in fact, might make matters worse. The core of the sexual assault problem on college campuses is one of character, not errant drinking or drug abuse, and prohibition will make it harder, not easier, to address this problem.

The ban is also ill-informed, based on the most recent evidence on campus sexual assault analyzed by Christopher Krebs at RTI International and his colleagues for the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. In-depth surveys of students and sexual assault victims at nine colleges and universities found that offenders may have been under the influence of alcohol or drugs in 59% of the rape cases reported by survey respondents, and the percentage on different campuses ranged from 47% to 71%. Rape victims reported being under the influence of alcohol or drugs in 63% of the incidents, ranging among the campuses from 43% to 75%. Among those victims reporting they were raped, about half said they were incapacitated by drugs or alcohol at the time of the incident where as about about 15% of those reporting incidents of sexual assault indicated they were incapacitated. Of course, these are still a high percentages of use and abuse associated with assault—alcohol and drugs are still important factors—but these figures suggest the impact of a ban will be on the margins, not a major shift in behavior.

Moreover, these data—as well as the more general ban—ignore the fact that alcohol and drugs are used extensively on today’s campuses in responsible ways and not abused in the vast majority of cases. The bans adopt a blanket policy that might be triggered by a particular incident, but doesn’t reflect actual patterns of use or abuse. Like most attempts to regulate moral and ethical behavior that is already embedded in culture, abusive activities are more likely to be pushed underground where they are less likely to be monitored and where moderating cultural influences are less likely to be felt. In short, the negative effects of these behaviors could very well become worse and even more difficult to address.

At the core of the campus sexual assault problem on today’s campuses is the issue of character and the need to rebuild civil society based on the respect for individual human dignity. Rape and sexual assault occur because someone ignores the wishes, desires and intent of someone else—sexual contact occurs without the consent of the victim. Some offenders are sociopaths—they act without regard for the interests of others, including their victim. These are the people that use alcohol and drugs as a tactic for committing their offense, and may require incarceration to stop their predatory behavior. Banning alcohol of any type won’t stop these predators; they will simply find another vehicle to carry out their attack. Others, however, don’t realize the severity of the harm they create, falsely interpreting the effects of alcohol as an inhibition reducing drug when in fact it erodes and eliminates the ability of the victim (and offender) to use judgement and provide consent. These offenders need different strategies to addressing sexual assault and changing behavior to be respectful of individuals and the communities in which they live. A ban on alcohol and drugs, ultimately, deflects responsibility from the offender and the consequences of the decisions he or she makes.

In my mind, the victim in the Stanford rape case got it right when she responded to her offender’s disingenuous claim his assault was the result of drinking. She wrote:

Alcohol is not an excuse. Is it a factor? Yes. But Alcohol was not the one who stripped me, fingered me, had my head dragging against the ground, with me almost fully naked. Having too much to drink was an amateur mistake that I admit to, but it is not criminal. We were both drunk, the difference is I did not take off your pants and underwear, touch you inappropriately, and run away….

Again, you were not wrong for drinking. Everyone around you was not sexually assaulting me. You were wrong for doing what nobody else was doing….

Alcohol bans do the opposite of what needs to be done on college campuses to make inroads into preventing sexual assault and rape. Bans implicitly reject the idea that individuals can take responsibility for their actions, face the consequences, and change their behavior. Yet this is exactly what needs to happen on college campuses if teenagers are expected to mature into adults capable of managing their own lives and protecting others that are threatened.

College campuses may have problems with drinking and alcohol abuse, but prohibition will do little to curtail that problem. At the root of the sexual-assault problem as well as drug abuse is one of character—understanding the limits of drug use, the harm that can be caused by using drugs of all kinds in excess, and making the changes to behavior necessary to minimize that damage. That requires a different strategy and one that is centered on taking responsibility for individual actions and accepting the consequences.